Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

A new report from the Pandora Papers examines how the ultrawealthy use real estate for any number of ends.

For Beatles drummer Ringo Starr, the property in question was a Los Angeles mansion. Arzu Aliyeva, daughter of Azerbaijan’s president, purchased a London office building. The Legion of Christ, a wealthy religious order disgraced by a sexual abuse scandal, poured millions of dollars into rental properties across the United States. Starr, Aliyeva and the Legion are among hundreds of real estate owners or investors whose identities are revealed in the Pandora Papers…

The leaked records expose billions of dollars of spending by the rich and famous — celebrities and politicians, oligarchs and other members of the uber-rich. And they’re buying not only luxury real estate but also properties not typically associated with offshore purchases. Dairy farms in Tasmania, a shopping mall in Uganda and rental homes in American suburbs have all been bought directly or indirectly through offshore companies or trusts, the records show.

And there are real-world consequences beyond supermarket tabloid gossip-mongering.

Real estate is a stable investment that often appreciates in value. By purchasing property through a shell company, buyers can secure tax breaks and shield their identities from law enforcement authorities and creditors. Secrecy also empowers criminals, including money launderers and drug cartels. Their trade in real estate through offshore companies moves millions of dollars while avoiding scrutiny.

In the United Kingdom, a director of the National Crime Agency said he believed that dirty money had “skewed” London’s property market. The combination of asset security and secrecy has also made offshore holdings a haven for money and other assets from less stable economies. A growing body of evidence suggests that offshore purchases at the high end of the real estate market have a ripple effect, pricing out people lower down the property ladder.

It is also about how two Canadian legacy millionaires came to own dairy farms in Tasmania. Their father’s company made a fortune in Nigerian oil the old-fashioned way.

The Pandora Papers show that the two sons of a secretive Canadian businessman purchased four Tasmanian farms covering 2,550 acres over seven years. The brothers, Anthony and Stephen de Heinrich, used a complex offshore network, including a company in Singapore and two trust companies in Bermuda, to acquire the properties, the confidential records show. One purpose, according to a memo, was to take advantage of a tax agreement between Singapore and Australia in a way that would lower their ultimate tax burden.

The brothers are the sons of Stephen Paul de Heinrich, who helped create Addax Petroleum, an oil company operating in Nigeria. Company executives allegedly paid multimillion-dollar bribes to Nigeria’s oil minister in the late 1990s. The company’s Nigeria director was convicted of money laundering in France. The elder Stephen Heinrich was not accused of wrongdoing.

And then there’s Vladimir Putin’s alleged girlfriend and her apartment in Monaco.

When a fourth-floor apartment changed hands for $4 million in the fall of 2003, the buyer’s identity was hidden behind a British Virgin Islands company. The Pandora Papers reveal that the true owner of the shell company, and of the apartment, was Svetlana Krivonogikh, a former economics student from St. Petersburg who had worked as a cleaner to put herself through college.

At the time, according to media reports, Krivonogikh was in a romantic relationship with Putin and had, just a few months earlier, given birth to a daughter with no father listed in the birth records. Proekt has reported that Putin is the father. Krivonigikh did not respond to requests for comment from ICIJ’s media partners.

The story also explains how the autocratic Aliyev family, which runs Azerbaijan, came to be in business with a public trust headed by Elizabeth II of Great Britain, and how an Israeli settler group is using an offshore shell to buy up property in East Jerusalem. The rich are different from you and me. Their money is everywhere.

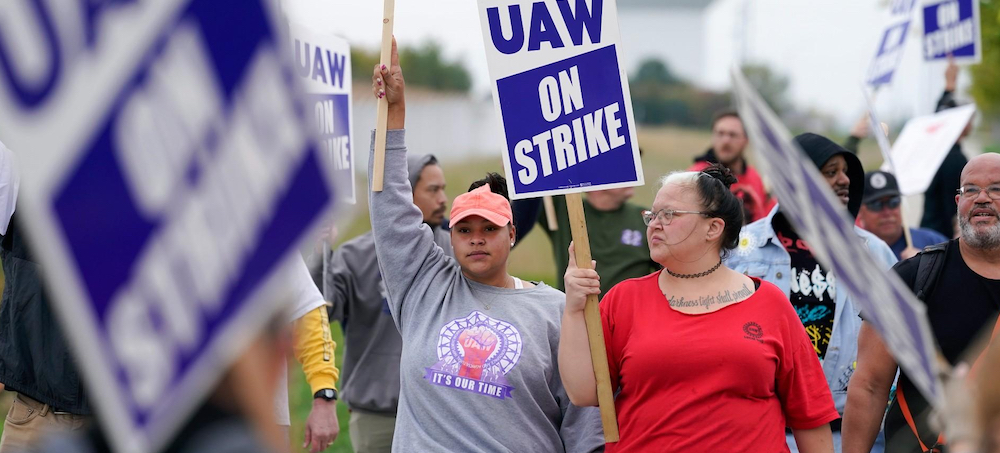

Members of the United Auto Workers strike outside of a John Deere plant in Ankeny, Iowa. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

Members of the United Auto Workers strike outside of a John Deere plant in Ankeny, Iowa. (photo: Charlie Neibergall/AP)

But it doesn’t take long for that sentimentality to morph into defiance. About 45 minutes later, I pull into the union headquarters of Local 84 in Ottumwa. The smoke from a burn barrel fills my nostrils. Inside, the union hall has enough canned goods to withstand the siege of Leningrad if the Russians had subsisted on stacks of canned Dinty Moore stew and cases of Mountain Dew.

The workers here build those green machines that glisten in the sun, specifically hay balers. They do their work amidst the noise and the heat of the nearby Deere Ottumwa Works factory. Many have shoulder and arm trouble from years of labor. During Covid, they were declared essential workers and did not miss a day of work.

Now it is time to negotiate a new six-year contract. For the first time in their lifetime, 10,000 John Deere workers hold the good cards. Corn and soybean prices are soaring, farmers are in the mood for new equipment. It’s not 1986 when Deere workers went on strike during a farming crisis. And it’s not 1997 when Deere forced through a contract that slashed retirement benefits with threats of closing factories here and in Akeny, 90 miles away.

But this is America in 2021. Fairness is weakness. Kindness is gauche. In October, Deere proposed a contract with a 5% raise and but no pension plan for new hires. With inflation, the workers would still be making less in real dollars than their predecessors. The company argued they would still provide decent medical benefits, an alleged perk in the only country of its kind without universal healthcare.

So 10,000 Deere hourly workers went on strike. Here in Ottumwa, men and women mill about in hoodies and Carhartt jackets preparing to hit the picket lines. It’s Day 17 of a walkout that has the not-humble dream of redressing two generations of worker humiliation. Oh, and one other thing: their strike has become a cause celebre, a sort of Lexington and Concord for all American working people tired of getting the short and sharp end of the stick.

Their opponent is formidable. The John Deere Corporation will make just short of $6 billion this year making tractors, balers, and other farm equipment that can run up to $500,000 apiece. They have a profoundly loyal client base that hold Deere festivals across the county, not unlike a Trekkie convention for implements that till the soil.

Deere’s stock price has quadrupled in five years. (A worker tells me buying stock at a discount is not a benefit provided by Deere to its hourly workers. “We do get a 10% discount on swag at the company store.”) And yet, more profit begets wanting even more profit. A John Deere executive promised on an earnings call in 2019 that the company would increase yearly operating profits to 15% by 2022.

Meanwhile, Deere’s already low wages continued to sink behind inflation after the company took away cost-of-living raises in the 2015 bargaining agreement. That kind of avarice has been duly endured by Deere workers, who have been told by management to shut up and eat your frozen pizza lest we ship your jobs overseas.

Of course, that’s not the official Deere line. “One of the goals of our ongoing negotiations is to agree on how we can continue to share in the company’s success in the years ahead, which includes competitive pay for performance incentives for all employees, best-in-the-industry wages and benefits, and continued industry-leading healthcare,” says Jennifer Hartmann, Director of Strategic Media Relations for Deere. “Lastly, we wish to invest in the livelihoods of our employees so that they can have a dignified retirement.”

Exactly zero Deere workers believe this. And the bill has now come due. Worker shortages have swept the country. Republicans and the landed gentry have made a strategic and pr error: They claim the shortage is because pandemic benefits were too generous, and workers are lazing at home watching CSI repeats and eating Hot Pockets. That is exactly wrong. The pandemic left workers shouting ‘fuck that’ when it comes to returning to work in hot and dangerous plants for wages so low that they leave some union workers with large families eligible for food stamps.

Inside the hall, an intense bald man dressed all in green as if he is about to go on a special ops mission thrusts a piece of paper describing what they pay at the nearby JBS Foods in Ottumwa.

“Did you see this?” asks Chris Laursen, a painter at Ottumwa Deere with 19 years of service. His eyes shine with the intensity of a Bernie Sanders delegate and a man who served as an Army Scout during the First Gulf War.

“That’s more than a lot of people make at Deere. Their offer is a slap in the face.”

It’s true, the per-hour rate at JB ranges at from $24 to $31 an hour, significantly higher than the $20 to $25 rate most make at Deere. “I make $20.92 after nineteen years,” says Laursen. “I could go slaughter pigs and get a raise.”

Laursen and I jump in his pickup truck and head over to check on picketers outside the Ottumwa Deere gates. He tells me that the UAW has leaned on individual members not to talk to the media and send reporters to the home office, but that’s not Laursen’s style. “I have a constitutional right to speak. They can’t stop that.” We pass row after row of small homes where many of the Deere workers live and raise their kids.

“We’re really at a turning point,” says Laursen as he honks at his fellow union members and slams the car to a stop. “This is really a crucial moment for America. Do we want to become like South America where there’s just rich and poor and no middle class? Because that’s where we’re heading if people like us don’t stand up and say, ‘no more.’”

We walk over to the strikers, a mixture of couples in Kiss t-shirts, retirees, men with beards and the grandchildren of workers. Laursen shows me their supply tent full of homemade brownies baked by supportive locals. For the first time in the hour since I arrived, Laursen takes a breath. “I’m sorry that I’m so worked up.” He pointed out at the workers carrying signs. “It’s just that a way of life is at stake.”

JOHN DEERE’S CORPORATE HEADQUARTERS and a significant number of its factories are in the Quad Cities, a series of small industrial towns that straddle both the Iowa and Illinois sides of the Mississippi River. For a century, it has been considered the premier corporation in the area. “It’s not true anymore,” says Laursen. “It’s sad.”

One of my first days in the area, a longtime worker gave me a driving tour of the area’s six Deere factories and the executive ground resplendent with geese and tranquil ponds. He blasts Ozzy from his SUV. On his arm is a UAW tattoo and a facsimile of his John Deere punch card complete with his employee number. His family have been Deere workers since World War II. His father was a Deere worker and is long dead. He brought home much more pay than his son, who’s driving me around.

The man doesn’t blink when we technically trespass on Deere’s executive drive, but he flinches when we pass some UAW workers walking a picket. That’s because, as Laursen told me, talking with the media is forbidden.

“Can you not use my name?” asks my driver, suddenly looking afraid. “I don’t want to get jammed up with the union.”

You may remember the UAW from their historic battle for factory workers in the auto industry in the 1930s and 1940s. More recently, you may know them for presiding over the closing of an iconic GM plant outside of Youngstown and two of their recent executives going to prison for graft. In May, former UAW president Dennis Williams was sentenced to 21 months in prison after being convicted of embezzling and various misdeeds that included Florida vacations paid for with union dues and a $1.1 million house built on union property.

The UAW’s corruption is so dense and gnarled that the United States government has assigned them a federal official to monitor their daily activities. Union defenders suggest that even during the union’s darkest days they were able to negotiate solid new contract with Ford and GM. (This last point would be hotly and profanely disputed by the workers who lost their job at the Chevy Cruze plant in Lordstown, Ohio.

Keeping the rank and file on mute seems an odd gambit. There would be no workers talking of working for thirty years and receiving a monthly pension of $900. There would be no talk of Deere workers taking side jobs to make car payments. These were all stories told me by Deere workers, some speaking on the condition of anonymity in order to not bring the wrath of the national union down on them. I asked Brian Rotthenberg, director of media relations for the UAW if a gag order had been put in place.

“It is common during bargaining and strikes, given the legal implications of the action, to ask for media to be referred to one source to clarify misinformation or potential legal issue,” Rotthenberg tells me when I ask about the gag order. “That said, a quick google search will show that members have been quoted. On its face the facts contradict your question.”

Not exactly, the fact a few brave members were willing to talk and contacted me surreptitiously or through the magazine’s tip line doesn’t exactly suggest an open marketplace of ideas between the UAW and its members.

Shutting down your most persuasive weapon — the workers — in a public relations war suggests a union as out of touch with the needs of the workers as Deere’s CEO John May, who makes nearly $15 million a year in total compensation. Proof of their cluelessness arose when the UAW negotiating team brought back the first tentative agreement reached with Deere. The union heralded an agreement including a 5% raise over the first five years and a reinstatement of cost-of-living allowance raises based on inflation. There was no ‘make good’ payment to make up for the lack of COLA over the six years of the previous agreement, so it left Deere workers making less in real dollars than they were in 2015.

There was no addressing the fact that Deere employees routinely retire between 55 and 60 with broken bodies after years of arduous work and must pay their own onerous health insurance until they hit 65 and qualify for Medicare. (Their other choice is to keep working. One Deere employee talked of “walking dead” employees shuffling to their stations intent on remaining of Deere insurance until they turned sixty-five.) There also were no meaningful changes to Deere’s pitiful retirement plan, well, except if you were a new hire. Then you got no pension, just the spin-the-roulette security of a 401k with the company providing some meager matching funds. Still, leadership thought it was a great deal.

“It is my belief that this tentative agreement will not only have an immediate impact on improving our members livelihoods but benefit the Deere membership for many years to come,” said Chuck Browning, UAW vice president and head negotiator.

The workers? They thought otherwise. Many of them gathered in early October at Moline’s TaxSlayer Arena to hear their union explain the agreement. After the negotiating team finished their presentation, workers moved to a series of microphones to express their dissatisfaction.

An African American machinist stepped up and began speaking. She got right to the point. “I’m going to retire from this place, and I want people coming after me to be able to come in here and have pride in what they do.” She paused for a second and her voice rose. “You’re killing it. You’re killing that pride.”

Speaker after speaker denounced the agreement in salty and straight language. One speaker pointed at a co-worker on the negotiating panel. “You know me, you know I can’t vote for this.”

“I wouldn’t have taken a million dollars to have been on that stage with those guys,” says a union worker.” Because I would have been scared for my life.”

That afternoon, the Deere rank and file voted down the agreement by 90 percent. They struck 48 hours later.

THE MORNING AFTER I ARRIVED, the local news blazed on about an accident outside the John Deere Parts Distribution Plant in nearby Milan, Illinois. A few hours later, it was announced that a Deere striker was trudging back to his car after a midnight to six a.m. picket shift. He was hit at a poorly lit intersection that had no cross walk. Picketers had been complaining about the dangerous crossing since the strike started. Richard Rich was 56 and had worked at Deere for fifteen years. He loved Judas Priest and pulling pranks on his friends and family. I drove over to the intersection later that morning. I found strikers standing at the intersection red-eyed and dazed. I approach a group of workers and asked them what happened. I was met with stony looks.

“Leave us alone. We ain’t got nothing to say.”

I drove around the corner and parked my car near Gate 5 of the plant. There were no picketers there, they had just been pulled off the line to mourn. Across the road, a man started a giant John Deere harvester. After warming up, the machine turned its angry blades through the already wasted corn stalks of a small field adjacent to the factory. I watched for fifteen minutes or so. Soon, the ground was flat, just a pile of dirt. The Deere machine left no trace that anything had grown there before.

MATT DeLOOSE TAKES A WARY look before he and his wife Tamra take a seat with me in the back of the cozy East Moline Coffee Company. With the no-media edict, you can’t be too careful. It’s a small town and everyone has a connection to Deere. He wears a cap pulled low over his bearded sunburnt face and sports a t-shirt that quotes JFK: “Those who make peaceful revolution impossible make violent revolution inevitable.”

DeLoose took medical retirement from the military and has worked at Deere for nearly twelve years. He admits that he voted for the 2015 contract out of fear, but no more.

“Now we have the power,” says DeLoose. “Deere has to do something or they’re making a big mistake.”

Like many of the workers I talked to, DeLoose pointed out that Deere was no longer the dream place to work and many of the workers stayed only because of the medical benefits and for the meager retirement benefit payoff. Before, getting a job at Deere involved a significant vetting program and a requirement of previous line experience. Deere might receive 150 applications for ten openings. Now, workers tell me they’re begging for workers.

“They’ve eliminated the high school diploma and GED requirements,” says DeLoose. “They’ve started hiring people with convictions. They’ve loosened their drug test restrictions. You have people that are coming in there that don’t know what a socket is, what a screwdriver is. That all gets back to the lack of competitive wages. We have workers who finish their seven-month probation period and then jump to another company because they are paying seven or eight dollars more an hour.”

Unfortunately, that information hasn’t trickled out to the public at large. While most of the local population has been supportive, DeLoose still hears the occasional ‘Deere is the best place to work, what are you guys complaining about?’ When he hears that, DeLoose tells them about forced overtime during the pandemic, as Deere would compel workers to do 12-hour shifts as parts trickled in slowly during the supply chain crisis. He tells them about how Deere shuts down for two to three months every year due to seasonal needs that can drop take home pay to $40,000 a year for the company’s lowest paid workers.

I first spotted DeLoose waving a UAW flag at a protest march in Moline. He splits his time at Deere as a forklift driver and as a UAW committeeman inside his factory. His grandmother and his father were union members, and his aunt was a prominent union activist at Deere decades ago. Like many I talked with, it was the presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders that reinvigorated his resolve.

Still, he has a complicated relationship with the international union headquartered in Detroit. He believes that the UAW decision to strangle information is counter-productive and leaves his fellow workers in limbo. He points back at the young woman working the counter. “I told her you might want to tell him, if he’s got an opportunity to go find another job and still do his picket duties, he should do it. We don’t know. And we’re not getting a lot of information back.”

DeLoose is not the only one. Many workers told me they were dissatisfied with the short amount of time from when they were apprised of Deere’s original offer and when they had to vote. “The UAW doesn’t want us to look at it too closely,” a worker told me. “And that’s my future at stake.”

DeLoose and his wife Tamra are trying to show the workers that someone at the local union cares for them. Tamra has ‘adopted’ a man on the line and is making sure he and his wife are getting enough formula and diapers for their baby. “I think even in the local a lot of people have been beaten down,” Matt tells me. “I try to give everyone my cell phone and go to the different pickets and tell them what I know.”

Matt has three kids including one who just turned eighteen.

“We were going to encourage him to apply to Deere,” says Tamra. “But he said he was going to be a big boy and go his own way.” She then offers a proud smile.

“I’m kind of glad he made that decision.”

BACK IN OTTUMWA, Toby Munley gives me a ride from the picket lines back to the union hall in his beat-up truck.

“You got to slam the door hard, it’s a salvage.”

Munley is a large man wearing a baseball cap and a St. Louis Cardinals hoodie. “I tell people that I have diabetes, C.O.P.D. and F.A.T.,” says Munley with a raspy laugh.

He wants to dispel me of any cliches I might have about the strike and the modern union movement. “We’re not all Democrats,” says Munley. “I bet half the people inside voted for Trump. You could go to the shittiest house in town, think it was abandoned, and you’d see a Trump flag. I don’t like it, but I understand it, they don’t think the Democrats have done anything for them.”

Munley and Laursen are, shall we say, at the other end of the political spectrum. They both used to be door to door salesmen and are beyond eager to get their point across. Both are ardent Bernie Sanders supporters with Laursen voting Green rather than supporting Hillary Clinton or Biden and Munley screaming ‘corporate whore’ at Clinton during one of her campaign speeches.

Both Laursen and Munley support union reform, speaking out at the last UAW convention. (“I’ll eat their fancy spread and drink their beer and then tell them they’re full of shit,” Laursen told me). They both support election reform that would transform the UAW from a delegate system not unlike the Electoral College to a one worker one vote that they insist will cut down on cronyism. Laursen and Munley’s actions on both political and labor fronts did not sit well with the more moderate members of their union where the two served as elected leaders. After four tumultuous years, they were overwhelmingly voted out by their local last spring.

“I think we made some mistakes,” says Munley waving at some union brothers. “Chris has gone to Standing Rock and was all about justice and the big picture. You have to keep it local and not some national thing.”

For Munley, that means honing the Deere strike to three main points: post-retirement healthcare for workers, wage equity with other manufacturers, and a return to the pension standards that Deere granted before 1997 rollbacks. “If I retire at sixty, I’ve got to scramble for coverage until Medicare kicks in,” says Munley. “God knows how much that is going to cost.”

But he can’t help himself. “It’s not just John Deere,” says Munley. “If we don’t get billionaires to pay for the roads they use and pay their fair share none of this will matter. It has to change.”

We shake hands and I jump out of the car and close the door with not enough heft.

“I said slam the fucking door, it’s a salvage,” shouts Munley.

He then smiles.

“Be good, brother.”

SHORTLY AFTER I LEFT OTTUMWA, the UAW and John Deere reached another tentative agreement. Details were released the next day. Across the board pay hikes were increased from 5% to 10%. Future pay raises in 2023 and 2025 was raised from 3% to 5%.

A ratification bonus — a very legal incentive to vote yes–was raised from $3,500 to $8,500. There were slight raises to the worker’s calcified retirement plans that would see retirement pensions raise for some from $750 a month to around $1100 a month. There was no movement on a retiree health program, but Deere offered $2,000 for each year of service that ostensibly could be applied to paying insurance premiums.

The offer was just good enough to divide the workers. The hardcore Chris Laursen was a surprise yes. “I think it is pretty fair and if we vote it down, the public might turn on us,” Laursen told me. Supporters of the second offer believed in realpolitik: There was no way one agreement could claw back all that was lost over the past thirty years. Chris’ buddy Toby disagreed. While he saw progress, it wasn’t enough. “They can do better wage wise, and pension and post retirement is still a must. We have to remember we will never have the scale tilted in our favor like this again.”

The vote was scheduled for Tuesday. Learning from their past mistakes, the UAW split Deere workers into smaller groups. Not that there wasn’t some score settling. The UAW didn’t even send a representative to the Waterloo union, long considered the most militant of the Deere factories. In the Quad Cities, a worker’s mic was cut off after he started talking about how John May’s raise was, percentage-wise, so much higher than what Deere was offering the workers.

That afternoon, I headed down to meet with Matt DeLoose at UAW Local 865 in East Moline. The parking lot was crammed with car, trucks, and motorcycles. Workers milled about in small groups, the mood somber, neither celebratory nor angry. Matt had told me on Sunday that he was going to vote yes, but something had changed. Even with the new concessions, Deere’s payout would be a tiny blip on their flush bottom line. Matt fidgeted with his hands going into and out of his pockets.

“I know we’re not going to get back everything we lost in one contract, but I started thinking if they can pay their board of directors $140,000 for coming to meetings on Zoom calls while we worked through Covid, they can afford to pay us more.” (Matt was right about the board of director compensation, but he didn’t mention that they received another six figures in stock).

DeLoose talked with his brother, another Deere worker and a Trump supporter. They reasoned that if Deere gave this much after three weeks, there was more room to bargain.

There was something else that bothered Matt: The international UAW was trying to sell them on the deal too hard. “They talked about how this was a good deal without causing detriment to Deere and that we wouldn’t have to worry about them outsourcing some of our work, said DeLoose. He nodded hello to another worker walking back. “The contract should sell itself. It shouldn’t need to make us afraid.”

But there was something else that happened. He listened to a song by the metalcore band Hatebreed called ‘I Will Be Heard.’

“Listening to that, a voice inside was telling me you got to go ‘no’ on this.”

He didn’t know what was going to happen. All he knew was that some of his union brothers had voted, left the hall, changed their minds, returned and exchanged their old ballot for a new one.

I asked him how he was feeling. “Check back with me tonight after they announce the results,” he said as he went to commiserate with his union brother. I still might not know how I feel.”

That night, before the results were announced, Matt went home and tried to figure out how to tell Tamra that he had changed his mind and voted no. They folded laundry together. Before he could figure out the right words, Tamra told him she needed to tell him something.

“I wish you would have voted no.”

Matt let out an exhausted smile.

“I did.”

Then they hugged.

AROUND 9 P.M., THE RESULTS came in. The union turned down the tentative agreement by a 45%-55%. On an election night where Virginia was lost and a socialist mayoral candidate in Buffalo was defeated by an incumbent who lost his primary but won as a write-in, it was a rare glimmer of hope. Still, it was a sort of defeat for the union members at Deere. The close vote suggested the rank and file were fractured and that Deere could wait them out. Winter was coming, and the UAW was paying its striking brethren just $275 a week. Some felt Deere would just wait out the union, starve their resources and return with a similar offer that a desperate union might jump at in January or February.

The next morning, I met with Matt and Tamra for a last cup of coffee. He looked exhausted but resolute.

“We’re going to hold the line.”

What comes next is unknown. Deere announced after the vote that the company had made their last and best offer. Some workers thought Deere would cave, others felt like it was going to be a long, cold winter on the picket line. It felt like Deere workers and American labor were on a precipice: they could either tumble to their deaths or somehow leap the chasm and enter a brighter tomorrow.

Right now, all Matt and Tamra could do was hold hands. They gripped each other tightly and then released them.

And then Matt picked up a pen. He started filling in an application for a job at the East Moline Coffee Company.

Central American asylum seekers wait as U.S. Border Patrol agents take groups of them into custody near McAllen, Texas. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Central American asylum seekers wait as U.S. Border Patrol agents take groups of them into custody near McAllen, Texas. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

Both Republicans and Biden say $450,000 payouts are too high.

Some 5,600 families were intentionally separated in immigration detention under former President Donald Trump in 2017 and 2018 after they tried to cross the southern US border without authorization, and about 1,000 families have yet to be reunited. Children taken from their parents were placed in foster care, the homes of relatives in the US, and federal detention centers, while their parents were detained separately. About 940 claims have been filed so far that would potentially be part of the settlement.

For those families, the $450,000 figure reflects the price of dealing with what could be lifelong psychological and health consequences of the trauma of separation, as well as, in some cases of separated children, physical and sexual abuse they experienced while in foster care and in US custody. Many advocates question whether this amount is really sufficient given the depth of the families’ trauma — and how long-term its effects could be.

“There’s no amount of money, or anything really, that is ever going to make something like that okay,” said Conchita Cruz, co-executive director of the Asylum Seeker Advocacy Project, which has represented separated families and is part of the ongoing negotiations.

But to some US officials, $450,000 seems too high a price.

While eager to make amends for the family separation policy on the campaign trail, Biden said Wednesday that settlements of that size were “not going to happen” and admonished reporters for “sending that garbage out.” White House deputy press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre later clarified that Biden supports settling with separated families if it is less costly than continuing litigation, but not for the amount of $450,000. The DOJ has said that price is too steep as well.

Republicans have seized on the issue, seeking to weaponize it against Biden. Nearly a dozen Republican senators recently argued in a letter to the White House that a settlement “would financially reward aliens who broke our laws” and “encourage more lawlessness” at the southern border, where the Biden administration has continued to uphold hardline Trump-era enforcement policies, which facilitate the mass expulsions of migrants.

Texas Sen. Ted Cruz has ridiculed the idea.

But while Republicans — and Biden — have dismissed the efforts to secure what might seem like a very large settlement for separated families, it’s important to put that number in context. The federal government has compensated victims of its own policies before, including those subject to Japanese American internment during World War II, under which some 120,000 American citizens and residents of Japanese ancestry were sent to camps in the US following the bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japanese forces.

And advocates argue $450,000 is not an unreasonable amount given what separated families have endured, and will continue to suffer, as a result of their separation.

“There is robust evidence from pediatricians, mental health and public health experts that family separation causes significant trauma that can impact a child for years to come,” said Amy Fischer, Americas advocacy director at Amnesty International USA. “The trauma in this case was the point, explicitly used as a tactic by the US government to try and deter families from seeking safety in the United States. The US government then bears the responsibility to compensate families for this trauma that was caused.”

Separated families experienced intense trauma

Family separation carries long-term psychological and health impacts that might not manifest until years later, or worsen over time — outcomes that the US government predicted even before implementing the family separation policy.

Commander Jonathan White, who previously oversaw the government’s program providing care to unaccompanied immigrant children, told Congress that he repeatedly warned the officials who concocted the policy that it would likely have “significant potential for traumatic psychological injury to the child.”

A September 2019 government watchdog report confirmed that immigrant children who entered government custody in 2018 frequently experienced “intense trauma” and that trauma was even more acute for those who were “unexpectedly separated from a parent.”

Each child reacts to family separation differently. But psychologists have observed three main kinds of effects: Disruptions to their social attachments, increases in their emotional vulnerability, and (in some cases) post-traumatic stress disorder, said Lauren Fasig Caldwell, director of the American Psychological Association’s children, youth, and families office.

Children may face difficulty establishing relationships, resulting in social isolation. They may show signs of anxiety and depression, aggression, and difficulty regulating their emotions or coping with stress. Stress can hinder memory, attention span, and an individual’s abilities to plan, make decisions, and process information.

Fasig Caldwell added those symptoms could be only short-term or persist in the long run — or not even manifest until a child enters their teen years or adulthood. All of them could significantly hinder a child’s later success in school and in the workplace. Suicidal ideation stemming from PTSD and bipolar disorder may also crop up later in life, as might high-risk and self-destructive behaviors.

Beyond those psychological effects, some children were also subjected to physical and sexual abuse while separated from their parents. For instance, one 6-year-old child was hit in his foster home while separated from his father for months.

And when Honduran immigrant Daniel Paz was separated from his 7-year-old daughter Angie in May 2018, she was sent to a detention facility for children, where he says an immigration officer sexually abused her and told her that if she told anyone, she would never see her parents again. Angie said she also saw the same officer sexually abuse two girls who were even younger than her.

“The Angie the U.S. government returned to me is not the same girl they took out of my arms in that detention center,” Paz wrote in Newsweek after their reunification.

Overall, these forms of abuse can have severe, long-term impacts on a child’s physical and mental health and later sexual adjustment, and may also erode their trust in adults to care for them.

Separated families should be compensated for the extensive trauma they faced

While the money won’t undo the harms caused by US government officials, it would begin to help separated families move forward and serve as a public statement that what happened to them was wrong.

Settlement negotiations are still ongoing, and it’s not clear what framework might be used to determine how much compensation each family would get. But Fischer said that, in devising such a framework, lawyers should consider the long-term social, emotional, and physical impacts on the child, the age of the child at the time of separation, as well as what might be sufficient for families to secure long-term care and recovery from the trauma.

There are also historical models for administering compensation to victims of US government policies that could guide that framework. In 1983, a high-profile class action lawsuit demanded that the US government pay $27.5 billion in damages to survivors of Japanese American internment or their descendants, to redress, among other things, their psychological distress. The suit argued that the internment program was not militarily necessary as the government had claimed, but rather was motivated by “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.”

The case advanced through the appellate courts, including the Supreme Court, inspiring vigorous political debate before it was finally dismissed on a technicality. Though the litigation did not prevail, it galvanized political pressure to rectify past wrongs and ultimately led Ronald Reagan to sign the Civil Liberties Act in 1988, giving $20,000 in compensation to each survivor; around $46,000 in 2021 dollars.

There are other ways that the US government could help separated families, aside from compensating them.

Conchita Cruz said that there has been a push to get affected families free access to medical and mental health care and social services. That’s especially important given that many of them are noncitizens and might not be eligible for public health insurance programs, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Without insurance, continuous care often becomes prohibitively expensive. Though individuals who have been granted asylum are eligible for those programs, the process of obtaining asylum can take months or even years.

Lawyers have also been advocating for a more immediate legal pathway for separated families to remain in the US without fear of deportation, though it’s not clear whether Biden would support such a pathway.

Advocates believe that dismissing these potential solutions, as some Republicans have, is a way of trivializing the trauma of the separated families.

“The government can choose to defend instances of government officials abusing children in their custody or not,” Conchita Cruz said. “That’s really where we are.”

"Sen. Kyrsten Sinema's support for the filibuster has soured feelings among former supporters in the state." (photo: Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP)

"Sen. Kyrsten Sinema's support for the filibuster has soured feelings among former supporters in the state." (photo: Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP)

The senator’s support for the filibuster has soured feelings among former supporters in the state

Young, a voting rights activist and citizen of the Diné, or Navajo Nation, is appalled by Sinema’s refusal to reform or abolish the filibuster.

“She has betrayed her constituents,” Young, 31, said by phone this week. “The sort of inaction that she’s taking right now is an action and it’s making the BIPOC community, especially in Arizona, distrust her more and more as the days go by.”

Republicans have deployed the filibuster to block legislation brought by Democrats to safeguard voting rights four times this year. On Wednesday they thwarted debate on the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, named after the civil rights hero and congressman.

It is an issue that hits home for Young, who last year organized a second “Ride to the Polls” campaign in Arizona that led Indigenous people more than 20 miles on horseback to polling places so they could cast their votes.

“Her campaign was something that attracted us because back then she seemed to be a little more progressive than she is now. That’s the part that we’re all having trouble understanding. What happened?”

The bewilderment deepened late last year when Sinema nominated Young for the Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s Citizen Honors Award for her contribution to increasing voter registration and turnout. Young reflected: “The fact that nomination came from her and her office tells me that she knows the importance of the Native vote.”

“[But] she’s not protecting our right to vote and, if she doesn’t end the filibuster and these voting rights acts don’t get passed, that will affect us. We’re already seeing some of these voter suppression laws that have been passed earlier this year and how they will affect the Native vote.”

This has led to the oft-asked question: what does Sinema really want? “A lot of folks are talking about how she’s trying to stay bipartisan. She thinks that’s the key to everything that’s happening in the divisiveness that we’ve seen,” Young says.

“It’s very devastating to all of us Arizonans and those who trusted in her. That’s the point of this election process. We vote in and we elect leaders that should be held accountable and that’s what we’re doing now. We put faith in a leader that’s going to show up for us and protect us and fight for us and we’re not seeing that right now.”

Earlier this year the US supreme court upheld Arizona laws that ban the collection of absentee ballots by anyone other than a relative or caregiver, and reject any ballots cast in the wrong precinct.

Republicans, who control the governorship and both chambers of the state legislature in Arizona, are also pushing to end same-day voter registration, a move that would hurt the Navajo Nation, with 170,000 people and 110 communities spread over 27,000 square miles, mostly in Arizona.

Young explained: “Sometimes it’s incredibly difficult to get to the poll. It’s difficult to get anywhere, to even get to a hospital or a clinic or a grocery store, so making multiple trips to ensure that our vote is counted is nearly impossible for a lot of people.”

Young argued the case for protecting voting rights with Kamala Harris at a White House meeting and is collecting signatures of Navajo leaders to register their discontent with Sinema. She welcomes the prospect of another Democrat challenging her in a primary election one day.

The filibuster, which is not in the US constitution, enables the Senate minority to block debate on legislation. Barack Obama has called it “a Jim Crow relic”, a reference to its long history of thwarting civil rights legislation.

Apart from blocking voting rights legislations, Republicans have used it to block the creation of a 9/11-style commission to investigate the 6 January insurrection at the US this year. Activists regard eliminating the procedure as crucial to other issues including immigration reform and reproductive rights.

In a CNN town hall last month, Biden indicated willingness to “fundamentally alter the filibuster”, adding that it “remains to be seen exactly what that means in terms of fundamentally – on whether or not we just end the filibuster straight up”.

But just as on his economic agenda, senators Joe Manchin of West Virginia and Sinema stand in his way. Both have repeatedly defended the filibuster, with Sinema arguing that it “protects the democracy of our nation rather than allowing our country to ricochet wildly every two to four years”.

Just Democracy, a coalition led by Black and brown organizers, is coordinating with Arizona groups to step up the pressure on her to reconsider.

This includes a psychological thriller-style parody movie trailer, The Betrayal, about Sinema turning her back on people of color in Arizona, ending with: “Now playing in Sinemas near you.” It will be backed by anadvertising campaign in Arizona and run alongside horror content on the streaming service Hulu.

Channel Powe, 40, a local organizer, former Arizona school board member and spokesperson for Just Democracy, said: “We’re going to make it politically impossible for Senator Sinema to continue to stand by the filibuster. In this week of action we are creating a surround sound effect that pushes Senator Sinema on the filibuster. We wanted to share the terrifying consequences of the world that Sinema is enabling.”

Powe added: “Once upon a time, she was a mentor of mine in a 2011 political fellowship that I participated in. I looked up to her. Kyrsten used to be a fierce fighter for the people. But once she got to Congress, she turned her back on the very same people who helped her get her in office.”

A rally protesting Rikers Island at City Hall in New York, September 15, 2021. (photo: Rainmaker Photo/MediaPunch/IPX)

A rally protesting Rikers Island at City Hall in New York, September 15, 2021. (photo: Rainmaker Photo/MediaPunch/IPX)

Esias Johnson, 24, was found dead in September of an apparent drug overdose after telling his family he saw no way out of Rikers, local media reported. Johnson’s parents told the Daily News that correction officials failed to take their son to any of his three court appearances, preventing payment of his $1 bail.

The mother of Rikers inmate Brandon Rodriguez, 25, said she learned of her son’s suicide in August through Facebook. “I didn’t know he was in jail,” his mother, Tamara Carter, told the City, a nonprofit news outlet. “I found out through Facebook of his death.”

Fourteen local lawmakers who visited the jail complex in September said they were shocked by the conditions there and even observed an inmate’s suicide attempt. The lawmakers described seeing shower stalls being used as jail cells, fecal matter and urine lining the floors, and dead cockroaches next to spoiled food in the jail’s hallways, leading them to characterize the situation at Rikers as a “humanitarian crisis.”

The Department of Correction acknowledges the mounting issues inside of Rikers and insists it is taking measures to increase jail safety. Eight correction officers and four captains have been disciplined for failing to properly do their jobs in relation to the dozen deaths, according to the New York Times.

“Any death in custody is one death too many and we are deeply concerned about these tragic losses, which have taken place during an unprecedented staffing crisis,” Latima Johnson, spokesperson for the department, told Yahoo News. “We’ve taken aggressive measures to end the crisis, and they are beginning to work. ... We expect and demand further improvement in the weeks to come.”

Rikers Island, a 413-acre island in the East River between Queens and the Bronx, houses an estimated 6,000 inmates, the majority of which are awaiting trial and have not been convicted of a crime. Many of them suffer from mental illness and have been jailed for nonviolent offenses. The complex, which is New York City’s main jail, also employs thousands of correction officers.

Mayor Bill de Blasio blames Rikers’s worsening issues on an increase in correction officer absenteeism and backlogged courts, but critics also say de Blasio turns his back on the issue despite promising to close the troubled jail. In August, Gothamist reported, the daily number of correction officers calling in sick was 1,416, nearly double the number that called in sick that same month the previous year.

In late September, de Blasio visited Rikers for the first time in four years and left “upset” by what he saw. He highlighted the need for a faster intake process to reduce the jail’s population and a greater investment in health services as priorities, which had been laid out in a five-point plan he released two weeks prior aimed at addressing the challenges on Rikers.

Correction Officers’ Benevolent Association president Benny Boscio Jr., a frequent critic of the mayor, said the plan fell far too short for any meaningful change. In September, Boscio called the situation at Rikers a “sinking ship” due to misalignment with city leadership.

“We’re all for reform, but reform can’t be one-sided,” he said in an interview with PIX11 News.

Around the country, the number of deaths inside of jails continues to climb as jail populations swell. The Bureau of Justice Statistics recently released a comprehensive report on mortality data for local jails in 2018. There were 1,120 deaths reported nationwide that year, or 154 deaths per 100,000 people in jail. At its current pace, Rikers easily surpasses the death rate of the average jail.

“These preventable deaths are the tragic result of healthcare and jail systems that fail to address serious health problems among the jail population — both inside and out of the jail setting — and of the trauma of incarceration itself,” the Prison Policy Initiative, a think tank on criminal justice, noted of deaths in local jails across the country.

Of the 14 deaths reported in the New York City jail system this year, at least six were attributed to suicide, leading many city officials to push for increased public health resources. Nationally, nearly 30 percent of inmate deaths were due to suicide, according to data from the U.S. Department of Justice. Studies show that people in jail are vastly more likely to have mental health issues than people in the general population. The shock of confinement in grim conditions can spark or exacerbate these issues.

And these types of deaths usually happen quickly after incarceration. About half of those who died by suicide had been in jail for nine days or less, compared to more than 17 days for other causes of death.

At Rikers, dysfunction appears to be the norm. Over the summer, a detainee hijacked a transportation bus and rammed it into a brick wall at the complex, according to a New York Times account. Another inmate stole a guard’s keys and slashed the guard across the face and neck. Four inmates just filed a class action lawsuit on behalf of all prisoners who had to deal with the jail’s “summer of hell” this year, when the coronavirus pandemic added to the complex’s many woes.

City Council leaders in October 2019 approved a plan to close Rikers by 2026, which would replace the complex with much smaller jails meant to be more humane, but lawyers with clients on the island say the plan would do little to solve the systemic issues.

“You don’t close Rikers just to create another Rikers,” Olayemi Olurin, public defender at the Legal Aid Society, told Yahoo News. “It’s not like Rikers is the soil on the land that Rikers occupies. It’s the innate act of the prison system that was created and being maintained. Rikers didn’t just come out of nowhere, so if you go and remove Rikers, then it just creates more Rikers and puts more people in the jails. All of the same problems that exist in Rikers, you’re just putting them elsewhere.”

Mayor-elect Eric Adams, de Blasio’s successor, has called for a “balanced” approach to Rikers, saying that the prison should be closed but also emphasizing the conditions faced by prison guards and other staff.

“Everyone is talking about what is happening to the inmates,” Adams, a former New York police captain, told NY1. “But guess what? The correction officers didn’t do anything to end up in Rikers Island. They’re there to protect us.”

But the future mayor acknowledges that change is needed, his spokesman Evan Thies told Yahoo News.

“Eric has been fighting for reforms to improve the horrific conditions at Rikers for years, including substance abuse and mental health services, as well as a move to community-based jails and the closure of Rikers,” Thies said. “[In September] he also called for significant new investments at the existing jail to protect both inmates and correctional officers.”

With nearly two months left in the calendar year, Rikers skeptics fear the complex will add more names of men and women to the list of those who have died in jail in ways that perhaps could have been prevented. For Olurin, the Legal Aid Society public defender, it’s most important for the public to understand that people in the jail deserve a fair opportunity to live.

“Anybody who gets arrested in New York, this is where they send you,” she said. “So it’s not this place for especially bad people. Any of us could end up there. ... So I think it’s really incumbent upon us to humanize people.”

Philippe Rio, the Communist mayor of Grigny, France, was voted the world's best mayor. (photo: Jacques Paquier/Flickr)

Philippe Rio, the Communist mayor of Grigny, France, was voted the world's best mayor. (photo: Jacques Paquier/Flickr)

Philippe Rio from Grigny, south of Paris, has been voted the world’s best mayor. He told Jacobin about the local social programs that have made his Communist administration a global success story.

Yet there is also a fight to save the city from its plight — led by local mayor Philippe Rio, a member of the French Communist Party. In 2017, he organized the “Appeal from Grigny,” signed by hundreds of other mayors calling for investment in the banlieues. His innovative social programs and a COVID response based on locally issued emergency food vouchers this year saw him handed the biennial “best mayor in the world” award.

The prize given by the World Mayor Foundation hadn’t gone to a Communist before (and even this time around it was co-awarded to Rotterdam’s mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb, a member of that country’s Labour Party). But Philippe Rio’s administration has also had a wider impact in his homeland, especially through its lifelong education programs and its success in geothermal energy production, which has slashed residents’ bills.

Jacobin’s David Broder spoke to the mayor about life in Grigny, his political engagement, and the lessons of French municipal communism.

DB: You’ve been named the world’s best mayor after being nominated by Grigny residents and other elected officials. What does this recognition mean for you — and the city you represent?

PR: First, we had the surprise to be recognized among thirty-two cities, including Washington, Milwaukee, Bogotá, Buenos Aires, and New Delhi, as a city that had taken a lot of action during COVID-19 and in fighting poverty — both themes the London foundation focused on. Then, to be elected the world’s best mayor — well, that was something we never dreamed of.

We’re one of those areas that some wrongly call “no-go zones,” but which in truth express this country’s extreme inequalities. France has many billionaires, but Paris also has pockets of deep poverty and social and spatial segregation. In Grigny, half the population is under thirty and half the population is below the poverty line. This is France’s poorest city.

During the lockdown, we did what every town hall in France had to do — we reacted. And I emphasize the “we.” A mayor isn’t a superhero — we acted collectively to serve the public. During the onset of the pandemic, we built up a barrier against the incoming tsunami. Here the health care crisis immediately meant a social crisis; whenever there are economic setbacks, it’s us who suffer it quickest, and it takes time to pick ourselves back up again. It was the same with the 2008 subprime crisis: we’ve recovered from it somewhat, but we still aren’t at the level of before.

So, faced with an abrupt shock, we simply did our job: distributing masks, being in contact with the population, dealing with the food crisis.

Areas like ours are always at the heart of French political debate, and always being mistreated by the media — Éric Zemmour’s always banging on about the banlieues, security, and immigration. But it’s communities like ours that are building France’s future. So folks who live in Grigny suffer these fascist politicians’ messages that seek to exclude whole sections of the population.

When there’s Olympic champions or actors from the banlieue who make it in the United States, people clap. But as for the rest, we’re insulted and mistreated. So this award lifted our hearts, people called me up saying we’re the world champions. Life is hard here. But we’ve succeeded in our efforts and been recognized for them internationally. Even if the French media present us negatively, what they say about us isn’t true. That’s a tribute to Grigny as a working-class city, but also to the banlieues more generally. They, too, can be proud of our success.

DB: You’re a member of the French Communist Party (PCF) and, before becoming mayor, you were active defending tenants locally, in the Grande Borne housing estates. How did you get involved?

PR: I’ve been a member of the PCF since 1995 — since the last century. I’m often asked what it means to be a Communist. But I remember why I joined the party back then — and looking at France, today I’d have twice as much reason to join a movement whose guiding star is indignation against injustice.

I am myself a product of municipal-level communism. I’ve never been around what’s happening at the “top” of society, but rather the work of all those invisible activists — blue-collar workers, employees, and public servants — who devote their free time to helping others live better. It was they who trained me up in the life of associations, first of all on the sports field, which is about the people who give their time and money to helping you play in a football match.

In this context, you experience magnificent things, even if you come from a poor background like mine. My dad was an unemployed worker, my parents experienced the downgrading of the working class, and sometimes there wasn’t even much to eat. So I had the food aid and the Secours Populaire [a grassroots solidarity initiative], including from the Communist town hall.

We were almost evicted ourselves. And in our Grande Borne housing estate, the people who mobilized to stop others being kicked out of their homes were in the National Housing Confederation and the Tenants’ Aid. That included Communist militants, though not only them.

But I understood that the collective action being done by these invisible militants could change peoples’ lives. I found Communist activists because they were basically the only ones who were — are — still in the working-class estates. Not as much as in the past, but they were still around. So here I am, the product of that.

DB: As you said, Grigny has a very young population, but it’s also an area in which a lot of people don’t get qualifications. So what can you do, as a city hall, on education?

PR: I like that line from Nelson Mandela: “Education is the most powerful weapon we can use to change the world.” I believe that very much.

Some context: In Grigny, 50 percent of pupils leave the public school system without a diploma. This confirms another reality: the PISA [Program for International Student Assessment] rankings tell us that French schools are extremely unequal — and each successive study shows the gap’s growing. The republican school is meant to be egalitarian, in our land of liberté, égalité, fraternité. But that’s a state lie — for only half as many resources are given to a school in Grigny compared to the average in France in general. So the state is shaping people’s lives from the youngest ages. Our first act, in terms of what we can do in city hall, is to denounce these inequalities.

But as I said, I am the product of municipal communism. And part of this is the programs that Communists have built at the local level, even across very diverse territories. That means health care. That means the right to leisure, to holidays. Grigny is one of the progressive cities using local powers to achieve social emancipation.

The novelty of our educational approach — also inspiring other cities in France — is that for us, education also means culture and sport. So we have three tools at our disposal. We must do more and better schooling. We must do more and better culture. And we must do more and better sport. We might think that being hyperconnected through smartphones would allow us to talk to each other. But the loss of human contact means we need to weave the ties of community again.

Children’s success may be academic, sporting, or cultural, but the adult world is responsible for creating an atmosphere conducive to that. We’re aware that not all children will end up in the Grandes Écoles [elite higher education]. But there must be a platform for them to be full citizens. That’s also about providing lifelong learning. In Grigny, we have three schools, including one we created, which allows young adults, indeed all adults, to train when they don’t have a diploma. And the results are quite extraordinary.

We’re lucky to have a great chef, Thierry Marx, who has come to Grigny to create training schools for people who don’t have a diploma. We have an adult education center with five hundred trainees a year coming through who learn French, who train, who gain know-how, then go on into employment. We have another education center for health and social assistance.

We are inventive and innovative because we have no choice. The system is not made for us, and the answers provided from above do not correspond to our needs. So, as well as calling for more resources, we are obliged to create a side route, to change people’s prospects in life.

DB: You mention this problem of resources, and while you are a Communist mayor in Grigny, the regional and national governments are in the hands of politically very different forces. What can you do to get funding from them, especially when it comes to long-term investment?

PR: In our working-class neighborhoods we need to invent a new political narrative. I mentioned the scapegoating of whole areas — telling us that if France is going badly, it’s because of places like this. The events of January 2015 were an electroshock in France because the perpetrators of the attacks came from this country and grew up in the republican schoolroom.

For decades, mayors of different political persuasions, but who were in contact with the population, had been sounding the alarm. That’s our responsibility as elected representatives of the banlieue. To say “Wait a minute!” That whatever happens, these districts can’t be ignored, because we are the youth of France and will shape its future.

So, after the shock of the attacks, there was an important moment on October 16, 2017, with the Appel de Grigny for working-class neighborhoods, supported by associations and mayors of all parties — though not with the Front National, which was excluded — and with Jean-Louis Borloo, a recognized statesman in France, and two current candidates for the presidency, Anne Hidalgo [mayor of Paris] and Valérie Pécresse [president of the regional council].

They came together with a common republican demand, as the summer just before the Macron government had senselessly cut our already meager credits and, even worse, cut funding for neighborhood associations. That meant getting rid of forty thousand public-subsidized contracts overnight, on budgetary grounds, though it didn’t solve France’s budgetary problems.

So we made a national plan for the suburbs called Vivre en grand — living together, living large in the Republic. We want to reconcile the suburbs with the rest of France, because otherwise we’ll have a catastrophe. We made nineteen proposals. President Emmanuel Macron threw this report in the bin, but, for six months, the media allowed us to explain another story. The last time we’d talked about the suburbs in France for six months was during the 2005 riots. So local mayors and associations were sounding the alarm for a problem facing the whole country.

But then, last November 14, France announced the post-COVID recovery plan. Money was distributed everywhere — in rural areas, overseas territories, etc., but we had to ask, when is it going to be our turn, in working-class districts? It seemed the recovery train had passed without stopping in our station. But it’s in areas like this where the health and social crisis is worst. So we had to say stop. And the strength of this movement is that there were more than two hundred of us mayors writing to the president, both from the banlieues and even charming cities that have working-class neighborhoods, like Albi, Agen, or Cahors.

Then we had some meetings with ministers and the senior administration to make proposals, and, at the end of January, the prime minister came to Grigny, and eventually we managed to get them to release another €2 billion for urban renewal. So we’ve gone from sounding the alarm to getting solutions. We have a government that at first sometimes stubbornly refuses to listen to us — and I have huge differences with Emmanuel Macron. But at times like this, we have to rebuild the foundations of the Republic.

DB: You mentioned the stigmatization of areas like Grigny, which also fits with the obsession with identity and security in the buildup to the 2022 election. But, even if we don’t accept talk of “no-go zones,” there clearly is real violence and the state reaching certain areas as a purely repressive force. What can be done to change that?

PR: There’s no consensus on any issue in France, but policing is a cause of deep division. There is police violence, cases like Adama Traoré [a twenty-four-year-old who died in police custody in 2016] — reprehensible police actions against categories of French society. And I haven’t forgotten the police killed in their own homes. But the media debate is hysterical because it’s polarized only in terms of violence against the police or police violence, but they don’t talk about the other 90 percent of the issue — public policy, justice, community policing.

We got a police station in 2007, but in 2009, President Nicolas Sarkozy closed it down for the sake of reducing public spending. Mr Sarkozy posed as the man of security but cut ten thousand police jobs, and his decisions also broke the intelligence services. This, too, had its consequences for what we’ve experienced in France. There are terrible testimonies of former intelligence officials who explain that they had to stop following Mohamed Merah [an Islamist terrorist who murdered seven people in 2012] because they no longer had the financial means to do so.

France is the fifth-leading economic power but has the thirtieth or fortieth justice system in the world. The youth justice system is a disaster. For years, there has been a left-right debate, community policing versus RoboCop police, where police only intervene to restore order, but in real life that doesn’t work. And today the French police, without saying so, are in the process of redoing community policing, but after a delay of fifteen or twenty years.

DB: The region around Paris has an important history of municipal communism, and Grigny has been Communist-led for decades. But the party has also had setbacks in recent years, losing Saint-Denis in 2020. Since these city halls were first won back in the 1930s, there have clearly been huge changes in the world of work and the social profile of the banlieues, and Grigny has grown a great deal since the postwar decades. But, as “best mayor in the world,” what can you do to rebuild this kind of rooted presence for your party in the life of the local population?

PR: The Communist Party has its victories and defeats. Life’s like that — there are no strongholds and no election wins are guaranteed. We have to pick ourselves up and continually reinvent ourselves.

It’s true — today the working class has changed. But I can assure you, the poor are still here. When people ask me, what’s the difference, Philippe, between when you lived in Grande Borne forty years ago and today, I say it’s that then there was 5 percent unemployment and now the figure is 50 percent. With its renewed hunger to capture wealth, liberal society is also creating poor workers.

In France, mayors are the most respected politicians. People have a more positive image of us than MPs, whether they vote for us or not. So we have a special responsibility as a last defensive dam of the Republic, in a moment where people no longer believe what the president or national representatives say. That’s also why we’re working on proposing national solutions, to answer the questions people are asking me face-to-face. That means confronting the challenge of the social transition, but also ecological transition. As a nice line by Nicolas Hulot puts it, that means connecting the problem of the end of the world to the problem of how people can make it to the end of the month.

Here, too, we’ve had to take responsibility. The Grigny 2 housing trust — with five thousand dwellings and seventeen thousand inhabitants — had its heating and hot water cut off because there were unpaid bills. It relied on natural gas, which depends on fluctuations in world prices, just like how it’s going up today. We couldn’t control anything. So we made an alternative, geothermal project, which is 100 percent publicly owned. We got heat from two kilometers under our feet. We cut the bills by 25 percent and saved the planet fifteen thousand tons of CO2 in one year. Well, I’m a Communist. And at the same time, saving the planet at my level. We like to joke that Grigny has ratified the Paris COP agreement.

Romain Rolland said that even in a hopeless situation, to fight is already hope. I have mayor friends governing populations who are having difficulties but are also rich. It’s a little easier to do socialism in those conditions than with a population suffering like ours is. We don’t exactly have oil to tap. But we do have geothermal energy, and we do have a totally different vision of how education should be.

I draw great inspiration from what’s happening elsewhere in the world — in Latin America, in Spain, but also mayors in North America and elsewhere in Europe, and all these invisible activists working for the general interest. But as we can see [with the divided field for] the French presidential election, this political family — the humanist forces of social transformation — have to talk to each other. At the local level, municipalities have been won back by a union [of the Left] with a clear program and strong political breaks: in Lyon, in Bordeaux, and also in smaller towns and suburbs.

So I’m very sad about the national-level solution, and if you ask me who I’m going to vote for, I don’t know. But I really believe that local elected representatives have a role to play in this very complex situation, to maintain a thread of connection, to make sure that it doesn’t break. Because if we let go, I don’t know how our country is going to bounce back.

For 30 years the Arctic has been melting at three times the global rate. (photo: Getty Images)

For 30 years the Arctic has been melting at three times the global rate. (photo: Getty Images)

“They have just always been a revered species by people, going back hundreds and hundreds of years,” said longtime government polar bear researcher Steve Amstrup, now chief scientist for Polar Bear International. “There’s just something special about polar bears.”

Scientists and advocates point to polar bears, marked as “threatened” on the endangered species list, as the white-hot warning signal for the rest of the planet — “the canary in the cryosphere.” As world leaders meet in Glasgow, Scotland, to try to ramp up efforts to curb climate change, the specter of polar bears looms over them.

United Nations Environment Program head Inger Andersen used to lead the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, which monitors and classifies species in trouble. She asks: “Do we really want to be the generation that saw the end of the ability of something as majestic as the polar bear to survive?”

THE STATE OF SEA ICE

Arctic sea ice — frozen ocean water — shrinks during the summer as it gets warmer, then forms again in the long winter. How much it shrinks is where global warming kicks in, scientists say. The more the sea ice shrinks in the summer, the thinner the ice is overall, because the ice is weaker first-year ice.

Julienne Stroeve, a University of Manitoba researcher, says summers without sea ice are inevitable. Many other experts agree with her.

Former NASA chief scientist Waleed Abdalati, now a top University of Colorado environmental researcher, is one of them.

“That’s something human civilization has never known,” Abdalati said. “That’s like taking a sledgehammer to the climate system and doing something huge about it.”

The warming already in the oceans and in the air is committed — like a freight train in motion. So, no matter what, the Earth will soon see a summer with less than 1 million square kilometers of sea ice scattered in tiny bits across the Arctic.

The big question is when the Arctic will “look like a blue ocean,” said Mark Serreze, director of the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

Maybe as early as the 2030s, most likely in the 2040s and almost assuredly by the 2050s, experts say.

The Arctic has been warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. In some seasons, it has warmed three times faster than the rest of the globe, said University of Alaska at Fairbanks scientist John Walsh.

That’s because of something called “Arctic amplification.” Essentially, white ice in the Arctic reflects heat. When it melts, the dark sea absorbs much more heat, which warms the oceans even more quickly, scientists say.

THE POLAR BEAR CONNECTION

There are 19 different subpopulations of polar bears in the Arctic. Each is a bit different. Some are really in trouble, especially the southernmost ones, while others are pretty close to stable. But their survival from place to place is linked heavily to sea ice.

“As you go to the Arctic and see what’s happening with your own eyes ... it’s depressing,” said University of Washington marine biologist Kristin Laidre, who has studied polar bears in Baffin Bay.

Shrinking sea ice means shrinking polar bears, literally.

In the summertime, polar bears go out on the ice to hunt and eat, feasting and putting on weight to sustain them through the winter. They prefer areas that are more than half covered with ice because it’s the most productive hunting and feeding grounds, Amstrup said. The more ice, the more they can move around and the more they can eat.

Just 30 or 40 years ago, the bears feasted on a buffet of seals and walrus on the ice.

In the 1980s, “the males were huge, females were reproducing regularly and cubs were surviving well,” Amstrup said. “The population looked good.”

With ice loss, the bears haven’t been doing as well, Amstrup said. One sign: A higher proportion of cubs are dying before their first birthdays.

Polar bears are land mammals that have adapted to the sea. The animals they eat — seals and walruses mostly — are aquatic.

The bears fare best when they can hunt in shallow water, which is typically close to land.

“When sea ice is present over those near-shore waters, polar bears can make hay,” Amstrup said.

But in recent years the sea ice has retreated far offshore in most summers. That has forced the bears to drift on the ice into deep waters — sometimes nearly a mile deep — that are devoid of their prey, Amstrup said.

Off Alaska, the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea polar bears provide a telling contrast.

Go 30 to 40 miles offshore from Prudhoe Bay in the Beaufort Sea “and you’re in very unproductive waters,” Amstrup said.

Further south in the Chukchi, it’s shallower, which allows bottom-feeding walruses to thrive. That provides food for polar bears, he said.

“The bears in the Chukchi seem to be faring pretty well because of that additional productivity,” Amstrup said. But the bears of the Beaufort “give us a real good early warning of where this is all coming to.”

THE FUTURE

Even as world leaders meet in Scotland to try to ratchet up the effort to curb climate change, the scientists who monitor sea ice and watch the polar bears know so much warming is already set in motion.

There’s a chance, if negotiators succeed and everything turns out just right, that the world will once again see an Arctic with significant sea ice in the summer late this century and in the 22nd century, experts said. But until then “that door has been closed,” said Twila Moon, a National Snow and Ice Data Center scientist.

So hope is melting too.

“It’s near impossible for us to see a place where we don’t reach an essentially sea ice-free Arctic, even if we’re able to do the work to create much, much lower emissions” of heat-trapping gases, Moon said. “Sea ice is one of those things that we’ll see reach some pretty devastating lows along that path. And we can already see those influences for polar bears.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment