Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

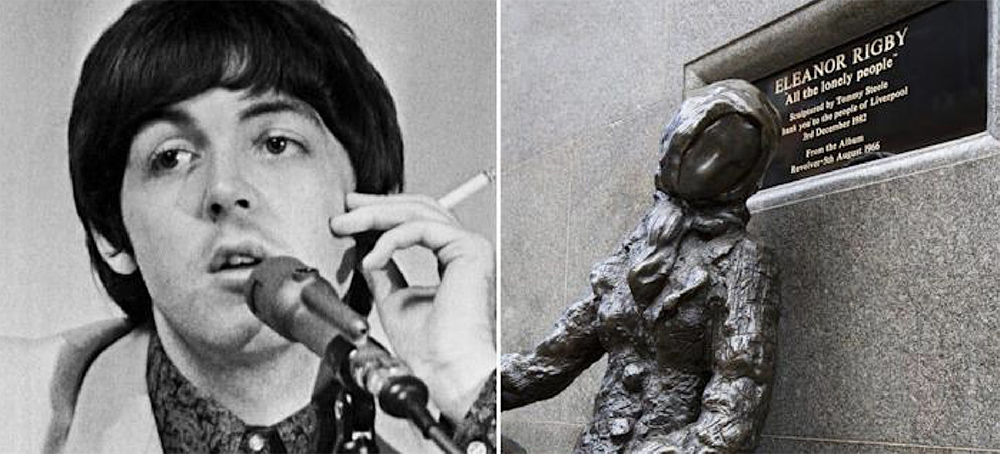

How one of the Beatles’ greatest songs came to be.

Growing up, I knew a lot of old ladies—partly through what was called Bob-a-Job Week, when Scouts did chores for a shilling. You’d get a shilling for cleaning out a shed or mowing a lawn. I wanted to write a song that would sum them up. Eleanor Rigby is based on an old lady that I got on with very well. I don’t even know how I first met “Eleanor Rigby,” but I would go around to her house, and not just once or twice. I found out that she lived on her own, so I would go around there and just chat, which is sort of crazy if you think about me being some young Liverpool guy. Later, I would offer to go and get her shopping. She’d give me a list and I’d bring the stuff back, and we’d sit in her kitchen. I still vividly remember the kitchen, because she had a little crystal-radio set. That’s not a brand name; it actually had a crystal inside it. Crystal radios were quite popular in the nineteen-twenties and thirties. So I would visit, and just hearing her stories enriched my soul and influenced the songs I would later write.

Eleanor Rigby may actually have started with a quite different name. Daisy Hawkins, was it? I can see that “Hawkins” is quite nice, but it wasn’t right. Jack Hawkins had played Quintus Arrius in “Ben-Hur.” Then, there was Jim Hawkins, from one of my favorite books, “Treasure Island.” But it wasn’t right. This is the trouble with history, though. Even if you were there, which I obviously was, it’s sometimes very difficult to pin down.

It’s like the story of the name Eleanor Rigby on a marker in the graveyard at St. Peter’s Church in Woolton, which John and I certainly wandered around, endlessly talking about our future. I don’t remember seeing the grave there, but I suppose I might have registered it subliminally.

St. Peter’s Church also plays quite a big part in how I come to be talking about many of these memories today. Back in the summer of 1957, Ivan Vaughan (a friend from school) and I went to the Woolton Village Fête at the church together, and he introduced me to his friend John, who was playing there with his band, the Quarry Men.

I’d just turned fifteen at this point and John was sixteen, and Ivan knew we were both obsessed with rock and roll, so he took me over to introduce us. One thing led to another—typical teen-age boys posturing and the like—and I ended up showing off a little by playing Eddie Cochran’s “Twenty Flight Rock” on the guitar. I think I played Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula” and a few Little Richard songs, too.

A week or so later, I was out on my bike and bumped into Pete Shotton, who was the Quarry Men’s washboard player—a very important instrument in a skiffle band. He and I got talking, and he told me that John thought I should join them. That was a very John thing to do—have someone else ask me so he wouldn’t lose face if I said no. John often had his guard up, but that was one of the great balances between us. He could be quite caustic and witty, but once you got to know him he had this lovely warm character. I was more the opposite: pretty easygoing and friendly, but I could be tough when needed.

I said I would think about it, and a week later said yes. And after that John and I started hanging out quite a bit. I was on school holidays and John was about to start art college, usefully next door to my school. I showed him how to tune his guitar; he was using banjo tuning—I think his neighbor had done that for him before—and we taught ourselves how to play songs by people like Chuck Berry. I would have played him “I Lost My Little Girl” a while later, when I’d got my courage up to share it, and he started showing me his songs. And that’s where it all began.

I do this “tour” when I’m back in Liverpool with friends and family. I drive around the old sites, pointing out places like our old house in Forthlin Road, and I sometimes drive by St. Peter’s, too. It’s only a short drive by car from the old house. And I do often stop and wonder about the chances of the Beatles getting together. We were four guys who lived in this city in the North of England, but we didn’t know one another. Then, by chance, we did get to know one another. And then we sounded pretty good when we played together, and we all had that youthful drive to get good at this music thing.

To this very day, it still is a complete mystery to me that it happened at all. Would John and I have met some other way, if Ivan and I hadn’t gone to that fête? I’d actually gone along to try and pick up a girl. I’d seen John around—in the chip shop, on the bus, that sort of thing—and thought he looked quite cool, but would we have ever talked? I don’t know. As it happened, though, I had a school friend who knew John. And then I also happened to share a bus journey with George to school. All these small coincidences had to happen to make the Beatles happen, and it does feel like some kind of magic. It’s one of the wonderful lessons about saying yes when life presents these opportunities to you. You never know where they might lead.

And, as if all these coincidences weren’t enough, it turns out that someone else who was at the fête had a portable tape machine—one of those old Grundigs. So there’s this recording (admittedly of pretty bad quality) of the Quarry Men’s performance that day. You can listen to it online. And there are also a few photos around of the band on the back of a truck. So this day that proved to be pretty pivotal in my life still has this presence and exists in these ghosts of the past.

I always think of things like these as being happy accidents. Like when someone played the tape machine backward in Abbey Road and the four of us stopped in our tracks and went, “Oh! What’s that?” So then we’d use that effect in a song, like on the backward guitar solo for “I’m Only Sleeping.” It happened more recently, too, on the song “Caesar Rock,” from my album “Egypt Station.” Somehow this drum part got dragged accidentally to the start of the song on the computer, and we played it back and it’s just there in those first few seconds and it doesn’t fit. But at the same time it does.

So my life is full of these happy accidents, and, coming back to where the name Eleanor Rigby comes from, my memory has me visiting Bristol, where Jane Asher was playing at the Old Vic. I was wandering around, waiting for the play to finish, and saw a shop sign that read “Rigby,” and I thought, That’s it! It really was as happenstance as that. When I got back to London, I wrote the song in Mrs. Asher’s music room in the basement of 57 Wimpole Street, where I was living at the time.

Around that same time, I’d started taking piano lessons again. I took lessons as a kid, but it was mostly just practicing scales, and it seemed more like homework. I loved music, but I hated the homework that came along with learning it. I think, in total, I gave piano lessons three attempts—the first time when I was a kid and my parents sent me to someone they knew locally. Then, when I was sixteen, I thought, Maybe it’s time to try and learn to play properly. I was writing my own songs by that point and getting more serious about music, but it was still the same scales. “Argh! Get outta here!” And, when I was in my early twenties, Jane’s mum, Margaret, organized lessons for me with someone from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where she worked. I even played “Eleanor Rigby” on piano for the teacher, but this was before I had the words. At the time, I was just blocking out the lyrics and singing “Ola Na Tungee” over vamped E-minor chords. I don’t remember the teacher being all that impressed. The teacher just wanted to hear me play even more scales, so that put an end to the lessons.

When I started working on the words in earnest, “Eleanor” was always part of the equation, I think, because we had worked with Eleanor Bron on the film “Help!” and we knew her from the Establishment, Peter Cook’s club, on Greek Street. I think John might have dated her for a short while, too, and I liked the name very much. Initially, the priest was “Father McCartney,” because it had the right number of syllables. I took the song to John at around that point, and I remember playing it to him, and he said, “That’s great, Father McCartney.” He loved it. But I wasn’t really comfortable with it, because it’s my dad—my father McCartney—so I literally got out the phone book and went on from “McCartney” to “McKenzie.”

The song itself was consciously written to evoke the subject of loneliness, with the hope that we could get listeners to empathize. Those opening lines—“Eleanor Rigby / Picks up the rice in the church where a wedding has been / Lives in a dream.” It’s a little strange to be picking up rice after a wedding. Does that mean she was a cleaner, someone not invited to the wedding, and only viewing the celebrations from afar? Why would she be doing that? I wanted to make it more poignant than her just cleaning up afterward, so it became more about someone who was lonely. Someone not likely to have her own wedding, but only the dream of one.

Allen Ginsberg told me it was a great poem, so I’m going to go with Allen. He was no slouch. Another early admirer of the song was William S. Burroughs, who, of course, also ended up on the cover of “Sgt. Pepper.” He and I had met through the author Barry Miles and the Indica Bookshop, and he actually got to see the song take shape when I sometimes used the spoken-word studio that we had set up in the basement of Ringo’s flat in Montagu Square. The plan for the studio was to record poets—something we did more formally a few years later with the experimental Zapple label, a subsidiary of Apple. I’d been experimenting with tape loops a lot around this time, using a Brenell reel-to-reel—which I still own—and we were starting to put more experimental elements into our songs. “Eleanor Rigby” ended up on the “Revolver” album, and for the first time we were recording songs that couldn’t be replicated onstage—songs like this and “Tomorrow Never Knows.” So Burroughs and I had hung out, and he’d borrowed my reel-to-reel a few times to work on his cut-ups. When he got to hear the final version of “Eleanor Rigby,” he said he was impressed by how much narrative I’d got into three verses. And it did feel like a breakthrough for me lyrically—more of a serious song.

George Martin had introduced me to the string-quartet idea through “Yesterday.” I’d resisted the idea at first, but when it worked I fell in love with it. So I ended up writing “Eleanor Rigby” with a string component in mind. When I took the song to George, I said that, for accompaniment, I wanted a series of E-minor chord stabs. In fact, the whole song is really only two chords: C major and E minor. In George’s version of things, he conflates my idea of the stabs and his own inspiration by Bernard Herrmann, who had written the music for the movie “Psycho.” George wanted to bring some of that drama into the arrangement. And, of course, there’s some kind of madcap connection between Eleanor Rigby, an elderly woman left high and dry, and the mummified mother in “Psycho.”

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

The Food to Families program, touted by Ivanka Trump, gave tens of millions of dollars to unqualified firms and was also used to promote then-President Trump.

As a ProPublica investigation revealed last spring and as the new report further details, the Farmers to Families Food Box program gave contracts to companies that had no relevant experience and often lacked necessary licenses. The House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis, which released its report last week, found that former President Donald Trump’s administration did not adequately screen contractor applications or identify red flags in bid proposals.

One company that received a $39 million contract was CRE8AD8 LLC (pronounced “Create a Date”), a wedding and event planning firm. The owner compared the contract to his usual work of “putting tchotchkes in a bag.”

In response to the report, the firm’s CEO said in a statement, “We delivered far more boxes/pounds than many other contractors and as a for-profit company, we’re allowed to make a profit.”

The congressional report also highlighted the application of an avocado grower who was initially awarded a $40 million contract before it was canceled after a review. Under the section of the application that required applicants to list references, the farmer wrote, “I don’t have any.”

The Food to Families program was created by the Department of Agriculture in the early days of the pandemic to give away produce that might have otherwise gone to waste as a result of disruptions in distribution chains. The boxes included produce, milk, dairy and cooked meats — and many also included a signed letter from then-President Trump.

The program was unveiled in May 2020 by Ivanka Trump. “I’m not shy about asking people to step up to the plate,” the president’s older daughter said in an interview to promote the initiative.

According to congressional investigators, Ivanka Trump was involved in getting the letter from her father added to the boxes. The USDA told contractors that including the letter was mandatory. Food bank operators told the investigators the letter concerned them because it didn’t appear to be politically neutral.

On the first day of the Republican National Convention in August 2020, President Trump and his daughter headlined a nearby event to announce an additional $1 billion for the food box program. Then-Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue also spoke at the event and encouraged attendees to reelect the president.

A federal ethics office later found that Perdue’s speech violated a federal law that prohibits officials from using their office for campaign purposes. The USDA at the time disputed the notion that Perdue was electioneering, saying that Perdue’s comments merely “predicted future behavior based on the president’s focus on helping ‘forgotten people.’”

The yearlong congressional investigation also identified problems with the deliveries themselves, including food safety issues, failed deliveries and uneven food distribution. Some contractors also forced recipient organizations to accept more food than they could distribute or store.

Committee chair Rep. James Clyburn, D-S.C., said in a statement that the mismanagement of the program is another example of the previous administration’s failures.

“The Program was marred by a structure that prioritized industry over families, by contracting practices that prioritized cutting corners over competence, and by decisions that prioritized politics over the public good,” he said.

ProPublica also found that the Trump administration hired a lobbyist to counter the criticism that contracts were going to unqualified contractors.

President Joe Biden ended the program in May.

Representatives of the former president did not respond to a request for comment.

'We have entered a new political era, one in which the principles and strategies that guided the party during the Clinton and Obama eras no longer suffice.' (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

'We have entered a new political era, one in which the principles and strategies that guided the party during the Clinton and Obama eras no longer suffice.' (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

The ambition of Biden’s spending package reveals the distance that US politics has travelled since the Great Recession

Treating that fateful week as the moment when the promise of the Biden presidency vanished may be too hasty a conclusion, however. The difficult challenge facing Pelosi was to unite Democrats behind a second infrastructure bill much larger and more ambitious than the first. It was never going to be easy to pass that second bill, and not just because the Democrats were holding a slim majority in the House and the thinnest of majorities in the Senate. It is also the case that a bill of this size and scope has no clear precedent. We hear a lot about FDR’s remarkable accomplishment, passing 15 separate bills in the first 100 days of his New Deal administration in 1933. The Democrats’ second infrastructure bill, if passed, would have been equally remarkable. It is best understood as an attempt to compress the equivalent of Roosevelt’s fifteen separate initiatives into one giant piece of legislation.

It’s exhausting simply to read through the list of the second infrastructural bill’s major provisions: universal preschool, subsidies for child and elder care, a program of school lunches, paid medical leave, expansion of Medicare (and Obamacare and Medicaid), massive investments in a green economy, additional investments in physical infrastructure, a Civilian Climate Corps (modelled on FDR’s storied Civilian Conservation Corps), affordable housing, Native American infrastructure, support for historically black colleges and universities, and an expanded green card program for immigrant workers and their families. We’ve heard a lot about the way in which the filibuster warps American democracy and about the arcane process of “reconciliation” that, in a few instances, allows for a filibuster “workaround.” We’ve heard a lot less about how the Democrats, in difficult political circumstances, have come within two Senate votes of achieving a legislative breakthrough on a scale that rivals FDR’s legendary 100 days.

And despite pundit declarations to the contrary, Democrats’ attempt at breakthrough is not yet dead. It is true that the reconciliation infrastructural bill no longer has a chance of reaching an expenditure level of $4tn. If such a bill passes, it is likely to be in the $1.5-2tn range. The many major initiatives currently contained within it may have to be shrunk by a third. That will disappoint Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and their supporters, who had originally set their eyes on a $6tn package. Yet, history offers a different perspective. The Biden administration might still deliver a package of programs across its first year totaling $5tn: an estimated $2tn for a downsized reconciliation infrastructural bill; $2tn for America’s Rescue Plan already approved; and the $1tn for the bipartisan infrastructure bill that is sure to pass the House at some point. This “shrunken” 2021 package as a whole would still rival (as a percentage of GDP) government expenditures during the most expensive years of the second world war. It would exceed by more than five times the size of Obama’s 2009 economic recovery plan.

The ambition of Biden’s spending package reveals the distance that US politics has travelled since the Great Recession, when Obama relied for economic guidance on a group of economic advisors drawn from the neoliberal world of Robert Rubin and Goldman Sachs, and of Wall Street more broadly—figures such as Timothy Geithner, Lawrence Summers, Peter Orszag, and Michael Froman. Elizabeth Warren had not then launched her political career, and Sanders was a lonely voice in the Senate. They were certainly not regarded as Democratic Party heavyweights. They now are. That Biden ultimately sided with the progressives during the 27 September week is a sure sign of their influence.

The progressives’ influence is equally apparent in Biden’s decision, in the days leading up to the expected vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill, to nominate Saule Omarova to be Comptroller of the Currency. Omarova, a law professor at Cornell University, is a radical who wants to democratize and nationalize finance in America in ways never done before. In her legal writings, she has argued that the Federal Reserve ought to be turned into a people’s bank where Americans would keep their deposit accounts (rather than in private banks, as is currently the case). This newly configured Fed, in her vision, would also establish a “national investment authority” charged with directing Federal Reserve capital to projects that serve the public interest. Omarova may not receive confirmation from the Senate; even if she does, she may simply be a pawn in Biden’s campaign to get the mainstream Jerome Powell reappointed as Fed chairman. But by nominating Omarova, Biden has spurred a conversation already underway about how to restructure the Fed in ways that make it less of a cloistered institution serving elite interests and both more transparent and more responsive to the democratic will.

Omarova is hardly a singular figure in Biden circles. Stephanie Kelton, an economics professor at Binghamton University and a former chief economist for Democrats on the US Senate Budget Committee, has argued in a widely-read book (The Deficit Myth) that governments can sustain much larger deficits than conventional economic theory prescribes. High-volume government expenditures, properly targeted, she asserts, will not slow economic growth but enhance a “people’s economy.” Lina Khan, appointed by Biden to chair the Federal Trade Commission, believes that social media and e-commerce giants such as Amazon exercise the kind of monopoly power that damage both the economy and American democracy. She has authorized the FTC to scrutinize the practices of these corporate titans with a view toward either breaking them up or subjecting them to much stricter public regulation than they have yet known. More generally, she aims to restore a regime of public regulation of private corporate power that FDR and his New Dealers did so much to bring into being—and that the Reagan Revolution did so much to break up. The bipartisan fury directed at Facebook during congressional hearings last week suggest that Khan’s views may have broad popular appeal.

It is still too soon to know which of these progressive views and the governing proposals that issue from them will prevail. The Democrats are operating in a political environment far more hostile than what Roosevelt faced in 1933, when he enjoyed large majorities in the House and the Senate. If they fail to pass versions of both infrastructural bills this autumn, the Democrats will seriously damage their chances of maintaining their majorities in the House and Senate in 2022. But it is also true, as is the case with the populist mobilization that Trump has engendered on the right, that the new progressivism is not going away anytime soon. We have entered a new political era, one in which the principles and strategies that guided the party during the Clinton and Obama eras no longer suffice.

Gaige Grosskreutz (top) tends to another injured protester during clashes with police outside the Kenosha County Courthouse in Wisconsin, Aug. 25, 2020. (photo: David Goldman/AP)

Gaige Grosskreutz (top) tends to another injured protester during clashes with police outside the Kenosha County Courthouse in Wisconsin, Aug. 25, 2020. (photo: David Goldman/AP)

Gaige Grosskreutz, who was shot in the arm, filed a federal lawsuit accusing police of enabling militants to engage in deadly violence during the anti-police protests in 2020.

Rittenhouse, who was 17 at the time of the shootings, is charged with killing two people and injuring Grosskreutz during the demonstrations over the earlier police shooting of Jacob Blake. Rittenhouse has pleaded not guilty to the charges, and his trial is scheduled to begin next month. His lawyers have claimed he fired his gun in self-defense.

In the federal lawsuit filed Thursday, Grosskreutz alleged that Kenosha's "law enforcement officers and white nationalist militia persons discussed and coordinated strategy" that led to the shootings on Aug. 25, 2020.

"It was not a mistake that Kyle Rittenhouse would kill two people and maim a third on that evening," the lawsuit stated. "It was a natural consequence of the actions of the Kenosha Police Department and Kenosha Sherriff’s [sic] office in deputizing a roving militia to 'protect property' and 'assist in maintaining order.'"

The lawsuit names the city and county of Kenosha, the sheriff, and the former and current police chiefs as defendants, but it does not name Rittenhouse as a defendant.

A lawyer for Sheriff David Beth and Kenosha County said the allegations against them were false, and he added that he intended to file a motion to dismiss the case.

"The lawsuit also fails to acknowledge that Mr. Grosskreutz was himself armed with a firearm when he was shot and Mr. Grosskreutz failed to file this lawsuit against the person who actually shot him," the attorney, Samuel C. Hall, said in a statement provided to BuzzFeed News.

The city of Kenosha declined to provide comment and the Kenosha Police Department did not respond to BuzzFeed News' request for comment.

Grosskreutz, who sustained serious injuries and "lost 90% of his right bicep" in the shooting, is seeking unspecified damages for several alleged constitutional violations, including failure to intervene, conspiracy to obstruct justice, and free speech violations.

According to the lawsuit, Kenosha's authorities were aware of social media posts suggesting that armed individuals were about to descend on the city with the intent to hurt and kill demonstrators.

In a Facebook post, a self-proclaimed militia group called Kenosha Guard called for "patriots willing to take up arms and defend our City tonight against the evil thugs," prompting hundreds of responses, including threats of violence.

"Counter protest? Nah. I fully plan to kill looters and rioters tonight. I have

my suppressor on my AR, these fools won’t even know what

hit them," one reply to the post said.

The lawsuit stated that instead of stopping Rittenhouse and the militants from patrolling the streets, Kenosha's law enforcement officers offered them water and thanked them for their presence, with one officer saying, "We appreciate you guys, we really do."

Many officers who saw Rittenhouse brandishing his gun through the night did not question or detain him, even after several people yelled out that he had shot people, according to the lawsuit.

"Instead, Defendants deputized Rittenhouse and other armed individuals, conspired with them, and ratified their actions by allowing them to patrol the streets armed illegally with deadly weapons and shoot and kill innocent citizens," the lawsuit said.

Grosskreutz also alleged that officers' actions during the protests constituted racial discrimination and that they would have acted differently if Rittenhouse were Black.

"If a Black person had approached police with an assault rifle, offering to patrol the

streets with the police, he most likely would have been shot dead," the lawsuit said.

"If a Black child had shot three citizens with an assault rifle and was seen walking away from the scene of the shooting with the assault rifle in hand, while other citizens yelled he was an active shooter, he would have been shot dead."

Earlier this year, the family of Anthony Huber, who was fatally shot by Rittenhouse, sued the Kenosha sheriff and police departments, alleging that their officers' conduct "directly caused" Huber's death.

Four people, including Huber's partner, also sued Facebook in August for its alleged role in enabling the violence in Kenosha by empowering right-wing militant groups to organize using its platform.

UAW on strike. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

UAW on strike. (photo: Scott Olson/Getty Images)

#Striketober could bring the strike back into the popular consciousness.

The numbers are incredible:

More than 10,000 workers at John Deere went on strike last week for the first time in 35 years. Roughly 1,400 cereal production workers at Kellogg's factories walked off the job in early October.

More than 24,000 Kaiser Permanente hospital workers in California and Oregon have voted to authorize a strike. Some 61,000 film and TV workers were prepared to walk out this week until a temporary agreement was reached on Saturday. It would have been the largest Hollywood strike since before World War II.

The list of striking or on-the-verge of striking workers includes: whiskey makers, coal miners, steel workers, bus drivers, and grad students. By withholding their labor power, workers around the country are pressuring their employees to offer them a better deal for their work.

"There’s a new strike wave happening now," said Alexander Colvin, the dean of Cornell's School of Industrial and Labor Relations, noting that this strike activity didn't come out of nowhere and has slowly crept upward in recent years after the all-time lows of early 2000s. "The pandemic disrupted a lot of things and left workers dissatisfied and wanting to see change. That is combined with an increase in worker bargaining power. There are lots of job openings and high quit rates. Expectations are going up."

For most of the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, labor activity in the United States dwindled. But this fall's strike wave—which has been called #Striketober on Twitter and has received vocal support from politicians and celebrities—could help bring the strike back into the popular consciousness.

Why are all these massive strikes happening now? A few factors are at play. A tight labor market has given workers across the country newfound leverage to demand raises from their employers, who are having a difficult time finding and retaining workers who are willing to accept middling wages while risking their lives.

"This is about wages," a striking John Deere worker in Davenport, Iowa, told Motherboard last week. "With what other people are paying, it doesn’t matter if this is McDonald's or Wendy's. We’ve been stagnant compared to everyone else."

"It’s been steadily getting worse since I’ve been here as far as how I’m treated," said a striking Kellogg's mechanic in Battlecreek, Michigan. “[Kellogg's] has made it very clear that anybody new who starts would never have a path to a pension or premium health care. The main issue really is our future. Our future is not for sale."

Experts say workers are seeing wages go up around the country (some fast food chains are paying more than $20 an hour)—and are using this knowledge to collectively pressure their employers into paying them more and to refuse deteriorating working conditions. Kellogg's has proposed ending its workers' cost-of-living raises; meanwhile John Deere wants to lower raises for its workers so that they no longer keep up with inflation.

This newfound leverage workers have to demand more is compounded by the pandemic conditions. Many of the complaints from striking workers are not only related to wages, but about hours, scheduling, safety, and overwork.

It also coincides with a period of enormous profitability for many corporations, such as Kellogg's and John Deere, that thrived during the lockdown. Workers see their companies flourishing and executive compensation rising, while they are being asked to agree to worse retirement plans and more expensive healthcare plans, in many cases, after working 12-16-hour shifts for months without a day off during the pandemic, and they decide to strike.

"I look at #Striketober and what I see is people fed up with long hours and low wages," said Lane Windham, a labor expert at Georgetown University. "Long hours is a theme. That’s an issue with Kaiser [healthcare workers], [film and tv workers], and Kellogg's [production workers]. They’re being asked to sacrifice time with their families with no choice."

For most workers in the United States, who don't belong to unions, striking is not an option, and other forms of collective and individual protest have emerged. For example, Instacart gig workers who deliver groceries are in the middle of a collective work stoppage on the platform to demand higher pay. Non-unionized workers, particularly in low-wage jobs in the hospitality and service sectors, who legally cannot strike are using their leverage to quit their jobs in record numbers and find better paying ones. McDonald's, Wendy's, Chipotle, and Dollar General workers have quit en masse. In August, almost 3 percent of workers in the United States quit their jobs—an all-time record.

"While union workers are exercising their right to strike, millions of others are exercising what they have available to them—quitting jobs, voting with their feet," said Windham. "It’s a slow moving 'general strike.'"

As labor organizers and experts have long noted, strikes tend to have a domino effect. When workers see each other walk out and win, they inspire others to do the same. While the strike numbers are nothing compared to what they were in the 1940s—when at one point one in ten workers in the US went on a strike in a single year—the number of workers on strike in the United States is the highest the country has seen since the 1980s.

But there's only so much workers can do without a union, and union membership in the United States remains at a near all-time low. Only 6.3 percent of private sector workers in the United States are in unions. Until that changes, we're unlikely to see a strike wave that could rival the heyday of the U.S. labor movement.

Abya Yala International Women's Summit in Peru. (photo: News WEP)

Abya Yala International Women's Summit in Peru. (photo: News WEP)

The delegates condemned some "customs" that legitimize sexual assaults against women in their communities, such as the rape of girls by parents, uncles, or siblings.

"Our societies often despise our rights and see us as sexual objects. However, we know for sure that we have the right to fight for our rights," said Lourde Huanca, the president of the Peruvian Federation of Indigenous Farmer, Artisan, and Worker Women.

She also condemned Indigenous "customs" that legitimize sexual assaults against women, such as the rape of girls by parents, uncles, or siblings. To compensate the victims, she demanded that regional governments enforce therapeutic abortion and establish proper sentences for this crime’s perpetrators.

Indigenous women also called for respect for their food sovereignty, lands, traditional medicines, and treatments. In other remarks, the Peruvian delegates demanded that the State convene a constitutional assembly to pay its historical debt to Indigenous peoples.

"The new Constitution should recognize our identity, culture, and wisdom," they pointed out, adding that the constituent conventions of Chile and Bolivia are examples in this process.

In May, Abya Yala Indigenous women held their first summit in Bolivia and formed a defense committee to fight against violence and femicides.

The organizing associations plan to set up two annual meetings to discuss the challenges they face and to ensure that governments meet their demands. Guatemala and Mexico are likely to host the March and October 2022 summits, respectively.

In this Monday, Dec. 17, 2012 file photo, a herd of adult and baby elephants walks in the dawn light as the highest mountain in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, sits topped with snow in the background, seen from Amboseli National Park in southern Kenya. Africa's rare glaciers will disappear in the next two decades because of climate change, a new report warned Tuesday, Oct. 19, 2021, amid sweeping forecasts of pain for the continent that contributes least to global warming but will suffer from it most. (photo: Ben Curtis/AP)

In this Monday, Dec. 17, 2012 file photo, a herd of adult and baby elephants walks in the dawn light as the highest mountain in Africa, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, sits topped with snow in the background, seen from Amboseli National Park in southern Kenya. Africa's rare glaciers will disappear in the next two decades because of climate change, a new report warned Tuesday, Oct. 19, 2021, amid sweeping forecasts of pain for the continent that contributes least to global warming but will suffer from it most. (photo: Ben Curtis/AP)

The report released Tuesday warned that the current retreat rates of Africa’s glaciers — Mount Kenya, the Rwenori Mountains and Mount Kilimanjaro — are higher than the global average. If it continues, the mountains would be deglaciated by the 2040s.

Mount Kenya is expected to be deglaciated a decade sooner, the report found, which would make it the first entire mountain range to lose glaciers because of human-induced climate change.

The WMO made the findings in The State of the Climate in Africa 2020 report, which details how Africa is disproportionately vulnerable to the consequences of climate change.

The report was done in collaboration with the African Union Commission, the Economic Commission for Africa (ECA) through the Africa Climate Policy Centre (ACPC), and other international and regional scientific organizations.

The WMO’s report stated that Africa is witnessing increasing weather and climate variability, which leads to disasters and disruption of economic and ecological systems. In 2020, the region saw continued warming temperatures, accelerated sea-level rise and climate events like floods and droughts.

By 2030, up to 118 million “extremely poor people,” those living on less than $1.90 per day, would be exposed to droughts, floods and extreme heat in Africa if adequate measures are not put in place, the report said.

The report further found that climate change could further lower gross domestic product in sub-Saharan Africa by up to 3 percent in 2050.

Adaption costs in sub-Saharan African are estimated to be between $30 billion to $50 billion each year over the next decade to avoid even higher costs of additional disaster relief.

WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement that enhanced climate resilience is an “urgent and continuing need.”

“Investments are particularly needed in capacity development and technology transfer, as well as in enhancing countries’ early warning systems, including weather, water and climate observing systems,” Taalas continued.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment