Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Activists continue to call on Democratic leaders to pass the $3.5 trillion Build Back Better Act, which expands the social safety net and includes measures to address the climate crisis. Progressives remain resolute in their opposition to passing a bipartisan $1 trillion infrastructure bill unless it is paired with the larger package. The Build Back Better Act represents “economic investment in the lives of poor and low-wealth people in this country,” says Reverend William Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign. “The question here is not 'What will it cost if we do this?' What will it cost if we don’t do this?”

Democratic leaders are struggling to pass two major pieces of legislation: a $1 trillion infrastructure bill and the Build Back Better Act, a $3.5 trillion, 10-year package that would expand the social safety net and combat the climate emergency. On Wednesday, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer huddled with President Biden in the Oval Office, as fractures within the Democratic Party threatened to derail Biden’s legislative agenda. Progressive New York Congressmember Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez spoke about the divisions on MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow Show last night.

REP. ALEXANDRIA OCASIO-CORTEZ: We have two bills at present: one which covers — which underfunds most priorities across the board, so there are very few priorities that even get the full funding that they even need, and then there is the larger, what is known as the budget bill, reconciliation bill. That has the stuff that you’re going to feel in your everyday life: universal pre-K; we’re talking about college, you know, community colleges; we’re talking about expansion of Medicare, and we’re debating including vision and dental in Medicare, conversations about lowering the age of it; robust climate action, renewable energy. All of that stuff that you’re going to feel in your everyday life is in what is known as the Build Back Better Act, aka the reconciliation bill.

Now, when we were discussing the scope of this bill way earlier in the year, this was the original infrastructure bill. And we have a vast majority of Democrats, about 96%, that are in agreement of the entire agenda. Now a very small handful of Democrats, about 4% of the party, are trying to essentially split these two priorities up, you know, and I personally don’t think it’s an accident that the ones that a lot of lobbyists love are in the much smaller, underfunded bill, that don’t make prescription drugs easier to buy and more affordable, etc. And what they want to do is split them apart, force a vote on the first one, and because we have such narrow margins in the Senate and the House, you know, the read that we have is that they’ll just dump the second one, leave the other one out to dry and just never actually vote on it.

And so, the way that we bring our two parts of the caucus together is by saying, “You know what? My bill is bound up in your bill, and your bill is bound up in my bill. So, do I love this very, you know, what I would argue, a conservative, underfunded bill? No. But I will vote for it if we pursue them both together.”

AMY GOODMAN: So, that’s New York Congressmember Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez on MSNBC last night.

For more, we’re joined by the Reverend Dr. William Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, president of Repairers of the Breach. Last month, the campaign met with Speaker Pelosi to, quote, “put a face on the urgent needs of this moment.”

And I think, Reverend Barber, that is what’s missing, is, so often the corporate media, the mainstream media, takes on the language of — I won’t call them “moderate” Democrats. I mean, you have, for example, Senator Manchin in West Virginia — you’ve been holding protests in his state — who is the largest recipient of oil and gas funds of any senator in the country. It’s not that he is a moderate — a conservative corporate Democrat perhaps. And then you have Arizona Senator Sinema. Arizona and West Virginia, some of the poorest states in the country. She has a fundraiser with those who are opposed to restoring taxes on the wealthiest people in this country, although she used to be Ralph Nader’s campaign head in Arizona. What do you make of this, as she goes back and forth from fundraisers to the Oval Office, but they don’t lay out their alternative plan versus, as AOC puts it, 96% of the Democrats?

REV. WILLIAM BARBER II: Well, I think we, first of all — you’re right — have to stop using this crazy liberal versus moderate versus conservative language. This is not about that. This is about a moral crisis in our nation, a crisis of civilization, a crisis of our democracy.

If you think right now, we have two senators blocking voter suppression — dealing with voter suppression and protecting the process to vote that 56 million Americans used in the last election. And those same two senators are working on behalf of corporate greed and the corporations to block the economic investment in the lives of poor and low-wealth people in this country — which, by the way, is not even what we need. We need, actually, according to the Economic Policy Institute, $10 trillion over 10 years. And then you have these two senators, one from Arizona, Sinema — over 3 million people in her state are poor and/or low-wealth, 830,000 are uninsured, and 1.2 million make less than $15 an hour. In West Virginia, 42% of the state is poor and low-wealth, over 750,000 people; 350,000 make less than $15. And we could have seen this coming when Manchin and Sinema blocked raising the living wage earlier this year to $15. And Sinema danced when she did it.

And the mistake that I think Democrats are making — and we said this to the president and his handlers. We offered to bring to the White House poor and low-wealth people of every geographical area and diverse racially, with moral and religious leaders, economists, to have a meeting in the White House, and then for the people to come out and say, “You are voting against me.” They need to have people who need living wages at the mic. They need to have healthcare, home care workers at the mic. They need to have people who are facing homelessness and eviction at the mic. They need to have people that would benefit from child care at the mic. They need to have people who need living wages at the mic. But instead, what we got trapped in is whether it’s going to be $3.5 trillion, which is only $310 [sic] billion a year. And we’ve already spent $20-some trillion in war since September 11, so it’s not like we don’t have the money. We’re getting trapped into whether it’s 3.5 or 2.1, rather than showing America what this is really about. This is about those who stand with you versus those who stand with the corporate greed and the Koch brothers. I don’t know why in the world Democrats want to claim always to care for low and — poor and low-wealth people but then don’t want poor and low-wealth people to speak. Someone told us the other day that they were afraid that if they put poor and low-wealth people out front, that it might turn Americans off. That is absolutely ridiculous, when 140 million people in this country are poor and low-wealth in this nation today and 700 people are dying a day from poverty and more have fallen into poverty since COVID.

We have a crisis of civilization and a crisis of democracy. And we have a serious messaging problem when it comes to Democrats. And it seems that they would rather argue the numbers. Even, lastly, they say this is about whether or not you support the president. I love President Biden. Thank God for him. No, it’s not. This is about whether you support the people who have been hurt the most during COVID, the people who were the first to get infected, the first to get sick, the first to die, the people who have suffered in poverty and low wealth for years. The question here is not “What will it cost if we do this?” What will it cost if we don’t do this? And that’s the moral argument that we should be raising in this time. And it’s not about moderate versus liberal versus conservative. It’s about right versus wrong.

AMY GOODMAN: And the whole issue of who is represented — I mean, I think the polls show more than 70% of the people of this country support the $3.5 trillion, when asked about the issues that that bill, the Build Back Better Act, represents: issues of child care, of healthcare, pre-K, of climate action, of helping small businesses, of restoring power to working-class people, poorer people in the United States. This is overwhelmingly popular. And it’s so fascinating that the people who have come to the support of President Biden in the Congress are the Progressive Caucus, by far the largest caucus in the U.S. Congress — right? — about a hundred members. Pramila Jayapal heads that. And they are not necessarily the people that supported Biden as a candidate, but they are his fiercest defenders right now when it comes to this bill and saying, “If you don’t support this now, it’s going to fall by the wayside. And instead, roads and bridges will be paid for, but not all the other stuff that benefits the vast majority of people in this country.”

REV. WILLIAM BARBER II: Yeah, and roads and bridges and most of that money will go again to the corporations, and people know that. You know, Manchin wants a utility grid and bridges, but he doesn’t want to help, for instance, the 350,000 people in his own state who make less than $15 an hour, the people we have met with in his state who are protesting, who are poor and low-wealth people from Appalachia.

And you’re exactly right: Pramila Jayapal and Barbara Lee and others and them have come to the rescue, and they’re raising the right issues, that this is not about these normal Washington, D.C., moments. We’re in the middle of COVID. We’re in the middle of a pandemic where thousands and hundreds of thousands of people have died. And this COVID has exposed the fissures of poverty and race. And if there’s ever been a time we want to at least take a step in the right direction — we think in the Poor People’s Campaign it ought to be much more, and we have backing for that — but we at least ought to take this step.

But again, Amy, the big problem is that you keep saying this is who you’re for, but you don’t put the who in front of the American people. We said to President Biden and to the Democrats, “What you should do is, number one, go to West Virginia and meet with people in Appalachia who would benefit. Just go right in the heart of Manchin’s state. You’re the president of the United States. Go to Texas. Go to Arizona and meet with those people, and then come back and go to the well of the Congress, like Abraham Lincoln did, like Franklin Delano Roosevelt did and Lyndon Baines Johnson and Kennedy, and say, 'There are three infrastructures we must protect. This is not about Democrat versus Republican. This is about this country and the people of this country. First infrastructure, the infrastructure of our democracy, which is voting rights. Second infrastructure, the infrastructure of our daily lives, which is healthcare and wages and education and protecting the climate and more housing. And the third infrastructure is the infrastructure of our bridges and our waters and our technology. And we're not going to do it all. We’re not going to separate it, because this is who it will hurt.’ And then you point to the balcony, and you have people, and you tell their stories. You have that white farmer, poor farmer. You have that person from Appalachia. You have that person from the Delta of Mississippi. You have that person from the poor areas of the industrialized states of Michigan and Ohio. You put a face on this, so that it’s not just about numbers, but it’s about real people. And you give the people the mic.”

Imagine if America right now was hearing press conferences where the Democrats and those supporting it and the president was not just meeting with Sinema four times, but he actually had in the White House people from their state and meeting with them and telling them, and then those people came out and advocated for the bill, those people came out in front of the mic. That’s the kind of moral power and agency that poor and low-wealth people have. And I don’t understand for the life of me why his handlers are blocking this. We’ve offered it to them for months. I don’t understand why in the world they don’t let the people speak.

Abraham Lincoln — when we met with Pelosi, she reminded us Abraham Lincoln said public sentiment is everything. This notion of holding the line, you know where that came from? That came from a woman from Texas and a woman from West Virginia that said it to Nancy Pelosi. “Hold the line. Do not allow one of these bills to happen without the other. Don’t throw us under the bus. Don’t run over us. We’ve already been hit hard through COVID.” These are the people they should speak. And I pray that if this goes past this week, Democrats will retool their messaging, will retool their focus, will let the people speak.

We can help them. We can bring the people that could turn the conscience of this nation, because this is not about, again, Democrat — I mean, moderate versus liberal. This is about what kind of democracy we’re going to be and who we’re going to be. And we need to get away from just “Is it $3.5 trillion or $2.5 trillion?” Who will be hurt? What will happen if we don’t do this? What is the cost, long term, if we do not do this, if we do not lift the people that have been so beaten down, even before COVID, and have been beaten down even worse after COVID? That is the question of our day. And that is the crisis of this democracy that we’re in right now.

AMY GOODMAN: Reverend Dr. William Barber, I want to thank you for being with us, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign, president of Repairers of the Breach.

Ryan Williams. (image: The Atlantic)

Ryan Williams. (image: The Atlantic)

“Let me start big. The mission of the Claremont Institute is to save Western civilization,” says Ryan Williams, the organization’s president, looking at the camera, in a crisp navy suit. “We’ve always aimed high.” A trumpet blares. America’s founding documents flash across the screen. Welcome to the intellectual home of America’s Trumpist right.

As Donald Trump rose to power, the Claremont universe—which sponsors fellowships and publications, including the Claremont Review of Books and The American Mind—rose with him, publishing essays that seemed to capture why the president appealed to so many Americans and attempting to map a political philosophy onto his presidency. Williams and his cohort are on a mission to tear down and remake the right; they believe that America has been riven into two fundamentally different countries, not least because of the rise of secularism. “The Founders were pretty unanimous, with Washington leading the way, that the Constitution is really only fit for a Christian people,” Williams told me. It’s possible that violence lies ahead. “I worry about such a conflict,” Williams told me. “The Civil War was terrible. It should be the thing we try to avoid almost at all costs.”

That almost is worth noticing. “The ideal endgame would be to effect a realignment of our politics and take control of all three branches of government for a generation or two,” Williams said. Trump has left office, at least for now, but those he inspired are determined to recapture power in American politics. My conversation with Williams has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Emma Green: What do you see as the threats to Western civilization?

Ryan Williams: The one we have focused on at the Claremont Institute is the progressive movement. [Progressives think that] limited government, in the Founders’ sense—checks and balances, robust federalism, a fairly fixed view of human nature and the rights attendant to it—all has to give way to a notion that rights evolve with the times.

The biggest institutional part of [the progressive movement] is this large bureaucracy or administrative state, which is insulated from control by the executive or even, increasingly, by Congress.

I would say the leading edge of progressivism now is this kind of woke, social-justice anti-racism. It’s a threat to limited government because it seems to take its lead from scholars like Ibram Kendi, who has proposed a Department of Anti-racism that would basically have carte blanche control over local and state governments. His definition of racism is any policy that results in disparate outcomes for different groups. And we take issue with that. You always have different outcomes between different groups. Human nature is varied. We all have different talents. The pursuit of equal results is only going to be successful in a new woke totalitarianism. I realize that sounds a little hyperbolic, but that seems to be the road we’re on.

Green: We’re going to unpack “woke totalitarianism” in a second, but I want to make sure I’m understanding your starting point correctly. When you say Western civilization, it sounds like you’re not necessarily describing people situated in geography or time but rather a set of ideas that you believe are falling out of fashion or are being actively destroyed by various forces in society. Am I getting you right?

Williams: You can never really divorce a set of ideas and principles from the people in which it grew up. America is an idea, but it’s not just that. It’s the people who settled it, founded it, and made it flourish.

Green: Just to ask the question directly, do you mean white people?

Williams: No, not necessarily. I mean, Western civilization happens to be where a lot of white people are, historically, but I don’t think there’s any necessary connection between the two. The ability to believe in natural rights and a regime of limited government the way the Founders did is not reserved only to white people.

Green: So you believe that there are American citizens of other backgrounds who belong in Western civilization—not just white people.

Williams: No. I think “white” is a pretty arbitrary category—

Green: People of European descent.

Williams: Okay, fair enough. No, it’s not an exclusive inheritance of that.

Green: One beef in the Claremont universe is what you all call “Conservatism, Inc.”: the professional-class conservatives who do panel discussions and run multimillion-dollar think tanks that produce white papers that ultimately don’t lead to anything, in your view. You guys are basically a think tank too. Why aren’t you just a slightly different version of Conservatism, Inc.?

Williams: Fair enough. Our target is not to say that good work doesn’t go on at the large conservative think tanks. But we think we’re in a real regime crisis right now. Our political elites and cultural and corporate institutions seem to believe in a way of doing government that is fundamentally at odds with the original, founding view—or even the view of Lincoln. We disagree on what men and women are; on what human nature is; what rights are. That’s a real crisis. We would love if our bigger brethren focused exclusively on what we think are the real threats: identity politics; this ideology of anti-racism and wokeness, which you said we’ll get to; the notion that borders are anachronistic and even racist, and that citizenship is global rather than national; that China is our main rival; the rise of big tech.

Green: Let’s talk about identity politics and being “woke.” People throw those terms around a lot, and they can obscure more than they illuminate. What do you actually mean when you say you stand against them?

Williams: There are a few strands. The most ascendant one right now seems to be critical theory, which was born in France in the ’60s and migrated to American universities. It has birthed all of these academic centers—gender studies, anti-colonialism, African American studies. It has some core tenets: There’s no such thing as truth in politics; it’s all about narratives and power, and we can’t know truth, fundamentally. There’s no such thing as natural rights; politics is making sure discrete identity groups, especially the ones who’ve been oppressed over time, now have an opportunity to express themselves.

That means deconstructing and disrupting what was the dominant narrative for a long time, which was the Founders’ regime of natural rights. One of the institutional vehicles for it was the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was meant to fulfill the promise of the Declaration of Independence for Black Americans coming out of segregation. But the courts and administrative agencies quickly turned against the color-blind, equal-opportunity vision of the founding and toward affirmative action—this calculation of current oppressor or past oppressor, and the pursuit of equity and social justice. Now this seems to mean that we’re really not going to be where we need to be until all groups are equally represented and have the same outcomes for, say, home ownership, wealth, the proportion of CEOs, or members of Congress. That seems to be the goal of wokeism.

Green: I take it that you would not disagree with the basic spirit of the civil-rights movement, which was to disrupt the legal regime of racism enforced by the state primarily against Black Americans?

Williams: No, I don’t disagree with that.

Green: But you do disagree with how you see this manifest on the left today. Do you have an alternative vision of what racial justice or equality—or whatever term you would use—should look like in 2021? How should we address continuing, legally sanctioned discrimination, assuming you think such a thing exists?

Williams: A true regime of nondiscrimination is when the state cannot disadvantage or advantage any group based on their skin color or ethnicity. That’s the original promise of the Declaration of Independence. It is, in many ways, a color-blind Constitution.

The counter from the left is that there’s systemic racism that has built up over years by certain legal systems. I would have to see some real proof of that. The main evidence seems to be that there are disparate results, thus there’s systemic racism.

Green: Let’s take one concrete policy example. The prison system in the United States disproportionately incarcerates Black men. Reasons for this include laws around sentencing, such as three-strike rules, or the possession of certain drugs being punished more harshly than others. This is an area of policy where the left and the right disagree, fundamentally, about the role race has played in the creation of the current carceral system.

So I guess the question is, in your vision of America, is this a problem? And is it a problem caused by racism?

Williams: It would depend on what is driving the disparate results. We would have to separate out the extent to which sentencing is truly discriminatory—and it ought not to be, if it is—and the extent to which the high incarceration rate of Black Americans is due to their much higher propensity to commit violent crime.

Until we can talk about that—if we can acknowledge that on the left and the right—it would be a wonderful starting point to try to dig into some of the issues you’re talking about, like the different classification of drugs being more associated with one group or another. We have to start, though, with the acknowledgment that a lot more Blacks are in prison because they commit violent crimes at a much higher rate [than Americans of other races]. Whites commit violent crime at a much higher rate than Asians do, so I don’t mean to suggest a racial crime hierarchy. But it’s just a fact we have to acknowledge.

Green: But certain crimes are more likely to be seen by the state, right? It’s easier to enforce against petty theft than white-collar crime. The other thing you might say is, okay, there are poor Black communities where more crime happens, but there are reasons why that’s happening: Those communities have been systematically neglected over time. And we as a society should change that.

I’m pressing you on this because it seems like the people in your orbit spend lots of time opposing the progressive program, but I don’t see you articulating a vision of how to appropriately right these kinds of wrongs.

Williams: To the extent that we can discover real discrimination, solely on the basis of race, we ought to. But we need to reject the notion that different outcomes are de facto evidence of discrimination. There are plenty of examples of poverty, even acute poverty, not leading to crime. I think it has a lot to do with culture, family, and all the rest. I want us to be honest social scientists about the pathologies plaguing America.

Green: Glenn Ellmers wrote an essay for The American Mind about why the Claremont Institute isn’t conservative. One of the things he writes is that some people residing in the United States—“certainly more than half”—are not Americans in any recognizable sense.

What does it mean to declare that more than half of the people residing in the country are not truly American?

Williams: Glenn was, of course, being provocative and polemical. But if Claremont thinks real Americanism is a belief in the principles of the American founding, we have to acknowledge that a good portion of our fellow citizens don’t agree with our principles and conclusions about what politics is for. If we differ on those fundamental things, we’re really two Americas.

Even during the Civil War—I think we’re more divided now than we were then. As Lincoln said, we all prayed to the same God. We all believed in the same Constitution. We just differed over the question of slavery.

Green: This picture you’re painting of unity around a certain set of ideas, principles, and beliefs about the nature of man and God doesn’t feel accurate to the founding conditions of the United States. America was founded as a place where people who had really out-there ideas could come and live peaceably in geographic proximity to one another, eventually governed under a shared constitution. Lots of religious radicals were involved. America was founded on the principle that people needed to tolerate one another, but no more.

How is that different from today, when we are continuing to experience turmoil over who we are and what we believe and what our orientation as a nation should be?

Williams: Well, most of the Founders of America were Christians. There were radicals, to be sure. But there was much more consensus back then on what human nature is—on monotheism, broadly speaking, but really Christianity as well.

Of course, Maryland was a bunch of Catholics who wanted their own place. But there was much more consensus on what government ought to do: to secure the blessings of liberty and natural rights. First among them was freedom of conscience—your freedom to worship as you see fit. I would reject your assertion that pluralism ruled the day in the founding. Pluralism is a term that comes up much later in the American tradition, meaning that the regime is indifferent to the types of groups that are in the country. I don’t think the Founders would have maintained that at all. They thought natural rights were the possession of human beings across the globe, but the conditions for securing good government and protecting those rights were often unavailable. It took a certain bit of luck and civilizational tradition and learning and philosophy to get there.

In many ways, the miracle of America was to solve the problem that had plagued Western Europe for so many years, which was that every religious difference was an existential political difference that led to civil war and misery and depredation. With Madison and Jefferson leading the way, we solved the political-theological problem—that’s the fancy term from Leo Strauss. They solved it well enough that we could all live together as fellow citizens.

That consensus was around for quite a while—broadly speaking, constitutionalism and limited government. We disputed over those things, but everyone thought the Constitution was a good thing and that government ought to protect rights. The glaring problem that plagued us for many years was the obvious contradiction of slavery to the principles of the Declaration. But there weren’t really any Founders who defended slavery as a good thing. Maybe a few from South Carolina, but that was about it. There was a moral consensus, even if they lived up to it imperfectly, embodied in our constitutional culture. We’ve lost that. If we disagree that human biology is a good guide to male- and femaleness, we’re a long way from the consensus of the founding.

Green: Do you think America can hang together in 2021 without Christianity at its core?

Williams: I’m ambivalent about that question. I think it would be bad for America if that longtime Christian core disintegrated. The Founders were pretty unanimous, with Washington leading the way, that the Constitution is really only fit for a Christian people.

I would modify that a bit and say a majority Christian people could maintain that. But if you don’t think your rights ultimately come from a Creator, you’re halfway down the road to our modern confusion.

Green: Writing in the Claremont universe often has a dire tone to it. The essay “The Flight 93 Election” is one example of this, or that Glenn Ellmers essay.

The thing I always wonder is: What’s the end game? If you truly have a sense that the American project is in crisis; that our country is not one but two entities; and that what’s at stake is nothing less than our ability to be a free people governed under a shared constitution—are you guys, like, stockpiling weapons?

Williams: The ideal endgame would be to effect a realignment of our politics and take control of all three branches of government for a generation or two. The goal would not be the reconquest of blue America but rather the restoration of the constitutional regime that we think has been lost.

We have to find some modus vivendi to go forward. If we’re two Americas, one of the more perfect solutions might be the return of federalism—the feds laying off in many respects. Let red America be red and blue America be blue. It’s obviously more complicated than that, because even in red states you have plenty of Democrats, and vice versa. But we need to restore a robust federalism, one that allows states much more leeway. We’ve gone much too far into the realm of federal control, arbitrariness, and overreach.

Green: Republicans have not won the popular vote in a presidential election in several decades. Do you worry about a project of minority rule—trying to assert your vision upon a country where many, many people do not agree with even your basic premises about what the American republic should look like?

Williams: I reject the premise that just because the popular vote isn’t won, you don’t possess a constitutional majority. We have an Electoral College system for a reason. Democracy, for the Founders, was a means to the end of the protection of rights. They set up a republic, not a democracy. The rule of pure numbers was never the touchstone of justice for the Founders. But the persistent inability of the right to win popular majorities—that is a problem. Ours is a project of persuading our fellow citizens, even independents and Democrats, that the current regime is on the wrong track.

Green: As a descriptive matter, do you think you guys are actually speaking for a silent majority in America that’s actually sympathetic to your goals?

Williams: That’s a testable proposition. I hope so. Trump showed the way it could be done. That was just the beginning.

Green: Many on the right seem to no longer believe in reality. QAnon gets a lot of hype, but many people on the right promote stories and narratives that aren’t supported by evidence or facts, especially about the 2020 election.

Are you at all preoccupied with this problem? I’ve noticed, for example, that one of your Publius fellows this year is a legislative assistant for Marjorie Taylor Greene, whose views certainly do not line up with reality. Does that concern you at all?

Williams: We believe in truth and reason. The question is whose truth and whose reason. That’s part of the contested quality of our national politics. And it’s not just the right. A third of the country thinks the election was given to Biden fraudulently. That includes a lot of Democrats.

Our national standard at the elite-media level these days seems to be something far from the truth. We’re no Q fans at Claremont. But it should not be surprising that, in our ideologically divided times, we have real division over truth and reality. Our national elites, and especially media elites, seem to be an ideological wing of left America rather than neutral arbiters of truth. It shouldn’t be a surprise that a good portion of the disaffected right turns to alternative sources for their political information. Many of those sources are cranks and lunatics, but that’s also nothing new. We’ve always had a robust tradition of firebrands and conspiracy theorists. It’s very American, in a way.

Green: Your answer is strikingly postmodern: You seem to be elevating the existence of multiple narratives, which may or may not hold elements of the truth. It’s also mostly a critique of the other side—a lot of people hate the media and think they don’t say true things. But if you’re trying to articulate what truth is as it relates to the American founding and ethos and mission, I would think you would be singularly concerned with the affairs in your own house. Greene has said she doesn’t think 9/11 happened. She thinks the Rothschilds started wildfires using giant space lasers. We are in a fraught time for coming to a shared consensus about what reality is. Are you doing your part to keep your house clean?

Williams: On the MTG question, it’s always been part of our project to educate folks who work in national politics, policy, journalism, etc. So I don’t think it’s suspect in the least for us to improve the staff of Congress, no matter who the congressperson is. Of course we’re concerned in policing our own house and making sure that there are not, in our political and intellectual coalition, people who reject fundamentally what we think is right. That battle is ongoing.

But I will contest what you said. I didn’t mean to elevate the notion of competing narratives. People are increasingly unsure of where to get valid information. A huge contributor to that has been our elite media.

Green: Do you feel like there is a hopeful future for America, or do you think we are headed toward some sort of generationally defining conflict that could potentially be violent?

Williams: I worry about such a conflict. The Civil War was terrible. It should be the thing we try to avoid almost at all costs.

A lot of normal Americans just want to go about their daily lives, raise their families, and make sure that our kids are successful. It’s really not that ideological, ultimately. I place a huge amount of hope in that. At the national level—the elite level—we have to advance intellectual ideas that we think are true, and the politics that we think will be the most successful. But we underestimate the extent to which we can lower the temperature in America and move forward with a lot more unity.

Green: I’ll look for that the next time I read the Claremont Review of Books—that effort to make sure our temperatures are lowered.

Jones claimed the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax perpetrated by actors employed by gun-control advocates. (photo: Sky News)

Jones claimed the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting was a hoax perpetrated by actors employed by gun-control advocates. (photo: Sky News)

A judge rules Alex Jones showed "flagrant bad faith and callous disregard" in failing to comply with court orders to hand over documents to the parents of children killed in the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting.

Judge Maya Guerra Gamble in Austin, Texas, ruled the founder of right-wing website Infowars repeatedly failed to comply with court orders to hand over documents to the parents of children killed in the attack.

She entered default judgements against Jones, Infowars and other defendants for what she called their "flagrant bad faith and callous disregard" to turn over the documents.

The cases will now head to trial for juries to determine the amount of damages Jones and other defendants will have to pay to the families.

Jones claimed the attack, which resulted in the deaths of 20 children and six school employees, was a hoax perpetrated by actors employed by gun-control advocates.

Several parents then sued Jones and Infowars, as well as its parent company, for defamation in both Texas and Connecticut. The cases in Connecticut are pending.

They also claimed they had been harassed and sent death threats from Jones' followers.

Jones and Norman Pattis, his attorney, lambasted the Texas judge's ruling in a statement on Infowars.

"It takes no account of the tens of thousands of documents produced by the defendants, the hours spent sitting for depositions and the various sworn statements filed in these cases," they said.

"We are distressed by what we regard as a blatant abuse of discretion by the trial court. We are determined to see that these cases are heard on the merits."

Jones' lawyers have argued his comments were protected by free speech rights.

However, in a deposition linked to one of the suits, Jones acknowledged the massacre had occurred but denied wronging the children's parents.

In her ruling, Ms Gamble said Jones had engaged in a "consistent pattern of discovery abuse" in numerous cases related to the shooting.

The lawsuits were brought by Leonard Pozner and Veronique De La Rose, whose son Noah was killed in the shooting, and Neil Heslin and Scarlett Lewis, whose son Jesse was killed. The children were both six years old.

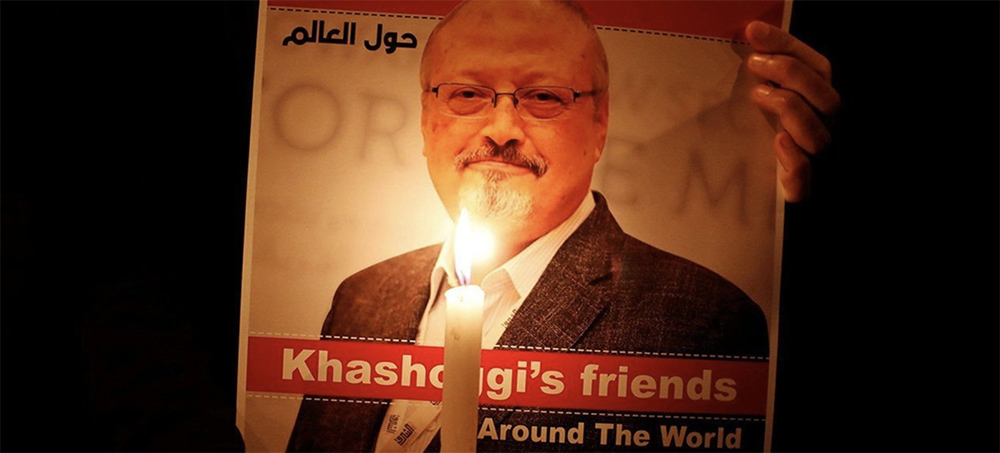

A vigil for Jamal Khashoggi. (photo: Alamy)

A vigil for Jamal Khashoggi. (photo: Alamy)

Abdulrahman al-Sadhan is an aid worker who worked with the Red Crescent in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. He also ran an anonymous Twitter account that posted satire about Saudi Arabia’s economy. In March 2018, he was taken from his office by Saudi security forces in plain clothes, allegedly after his identity was leaked.

For nearly two years, al-Sadhan’s family did not know what happened to him. Then, a relative in Riyadh received a call from him, in which al-Sadhan said he was being held at al-Ha’ir prison. His family endured another period of silence, punctuated by disturbing reports from those in contact with other prisoners that al-Sadhan faced torture and mistreatment. This year, in a secret trial, he was sentenced to 20 years and a further 20-year travel ban, which he is appealing.

“My family is exhausted. We and so many others should not have to spend days and years wondering if our beloved brother or son is safe, if he’s in pain, if he’s alive,” his sister Areej wrote in a Post op-ed in May.

Samar and Raif Badawi

The siblings Raif and Samar Badawi are among Saudi Arabia’s most prominent activists. Raif Badawi was a blogger who advocated for secularism and respect for minorities. He was arrested in 2012 on charges including apostasy and “insulting Islam through electronic channels.” He was sentenced to 10 years in prison and 1,000 lashes. Badawi received 50 lashes publicly in January 2015. (In 2020, Saudi Arabia announced it was abolishing flogging.)

Samar Badawi is a Saudi activist who advocated for women to be able to vote and drive, and challenged the male guardianship system. She was arrested with other defenders of women’s rights in July 2018 — just over a month after Saudi Arabia lifted its ban on female drivers — and charged with “communicating with embassies and entities abroad hostile to Saudi Arabia” and “unlicensed human rights activism.” She had previously been detained for seven months in 2010 on charges of disobeying her father. After nearly three years of detention, she was released from prison in June, but she remains barred from traveling; she has not spoken publicly about her ordeal. Her husband, Waleed Abulkhair — who also served as Raif’s lawyer — is in prison serving a 15-year sentence on spurious charges.

Eman al-Nafjan

“What’s it like being a Saudi woman? A common question I’ve come to expect from outsiders — even fellow Arabs,” Eman al-Nafjan wrote in an op-ed in the Guardian in 2011. “The restrictiveness of the guardianship system, gender segregation and a persistently sexist culture add up to create an exotic and mysterious lifestyle that is difficult to not only explain but also to comprehend.”

Al-Nafjan, the author of the Saudiwoman’s Weblog, courageously addressed these obstacles in her writing and work. The linguistics professor contributed to news outlets such as CNN and Foreign Policy, and regularly spoke about feminism and women’s rights in Saudi Arabia. She was arrested in May 2018, a month before Saudi women were legally allowed to drive. After nearly a year in detention, she was temporarily released in March 2019 but continues to face restrictions on her freedom. She was awarded the 2019 PEN/Barbey Freedom to Write Award alongside fellow Saudi writer Nouf Abdulaziz al-Jerawi and activist Loujain al-Hathloul.

Salman Aloudah

Salman Aloudah is an Islamic cleric and scholar. He was arrested in 2017, a day after he shared a message with his then-14 million Twitter followers calling for peace between Saudi and Qatari leaders. Though the Saudi-led blockade of Qatar ended in January, Aloudah remains in prison and faces the death penalty on 37 charges, including calling for a change in government, “joining” and “praising” the Muslim Brotherhood, and objecting to the boycott of Qatar.

The 64-year-old faced a secret trial in the Specialized Criminal Court in Riyadh. Since then, he has seen multiple hearings and sessions delayed and postponed. He was held in Dhahban prison, where his family says he was hospitalized for high blood pressure, and al-Ha’ir prison, where he was reportedly held in solitary confinement.

Mohammed Fahad al-Qahtani

Mohammed Fahad al-Qahtani is a lawyer and co-founder of the Saudi Civil and Political Rights Association (ACPRA), an independent human rights organization that has been disbanded. For its work documenting human rights abuses in the kingdom, he was arrested in 2012 as part of a sweep of activists, and sentenced in 2013 to 10 years in prison and another 10 years under a travel ban. Among his charges was “using the Internet to disseminate opinions, petitions, and statements against the government.”

In 2018, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award with Waleed Abulkhair — Raif Badawi’s lawyer and Samar Badawi’s husband — and Abdullah al-Hamid, a human rights activist described as “Saudi Arabia’s Nelson Mandela.” Al-Hamid died in detention last year, after his family said he was denied medical treatment in prison. Al-Qahtani has launched multiple hunger strikes in protest of prison conditions and tested positive for the coronavirus in al-Ha’ir prison earlier this year.

Omar and Sarah Aljabri

Sarah and Omar Aljabri are children of the former Saudi intelligence chief Saad Aljabri, who fled Saudi Arabia in May 2017 and remains in exile. The siblings have been targeted by authorities seeking to force their father, who was an adviser to former crown prince Mohammed bin Nayef, to return to Saudi Arabia.

In June 2017, while attempting to fly to the United States, Sarah and Omar were banned from leaving Saudi Arabia and had their bank accounts frozen. The next year, they were brought into the prosecutor’s office and interrogated without the presence of legal representatives. For 2½ years, they and their family were intimidated into silence. Then, in March 2020 — after being interrogated and pressured to persuade their father to return just days earlier — their house was raided, and they were disappeared. They have since been charged with money laundering and conspiracy to escape the kingdom unlawfully, and have undergone secret trials without due process. This year, their appeal failed, and lawyers found that their cases disappeared from the court docket on the justice ministry’s database.

Demonstrators take part in a protest against Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro in São Paulo, Brazil, on Oct. 2. (photo: Nelson Almeida/AFP/Getty Images)

Demonstrators take part in a protest against Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro in São Paulo, Brazil, on Oct. 2. (photo: Nelson Almeida/AFP/Getty Images)

Crowds parade through cities as polling shows president’s ratings sinking to new depths

Huge crowds paraded through downtown Rio on Saturday to voice their outrage at Bolsonaro’s response to a Covid outbreak that has killed nearly 600,000 people and dealt a heavy blow to the South American country’s economy.

“We have come to shout at the top of our voices: Bolsonaro’s place is behind bars,” Carlos Lupi, the president of Brazil’s Democratic Labour party, told thousands of flag-waving demonstrators who had gathered outside Rio’s municipal chamber under a ferocious midday sun.

“This crook who uses the Bible to trick the people … This worm! This wretch! He must go to jail!” Lupi bellowed to cheers of approval.

Jandira Feghali, a congresswoman from the Communist party of Brazil, urged Bolsonaro’s opponents to form a broad cross-party coalition against the president’s “fascist” administration. “600,000 lives have been lost,” Feghali told the demo. “We can wait no longer. It is time for us to scream out loud: ‘Bolsonaro out!’”

All morning dissenters had streamed into Rio’s historic centre, from across Brazil’s second-largest city and from all walks of life.

Renato Bezerra de Mello came with a group of artist friends, each of whom wielded a lacerated yellow and green Brazil flag. “This is how we feel about the state of our country. It’s in tatters,” the 61-year-old artist said.

“He’s an odious figure,” De Mello said of Bolsonaro, whom a record 58% of Brazilians now oppose according to a poll released on the eve of the protest. “He is the tip of the iceberg of what is worst in all of us.”

Antonia Pellegrino, a writer whose grandfather was a key figure in the fight against Brazil’s 1964-85 dictatorship, said she was attending her first anti-Bolsonaro rally since the coronavirus pandemic began, having recently been vaccinated.

“It’s invigorating and it is essential for us to be out in the streets to halt the process of destruction that our country is going through,” Pellegrino said as a column of protesters marched down Rio Branco avenue.

José Manuel Ferreira Barbosa, a decorator from Belford Roxo, a city on Rio’s rundown northside, said he had come to protest unemployment, soaring inflation and the spread of hunger that he blamed on Bolsonaro.

“The president has cut taxes on rifles but not for basic food,” said the 63-year-old, who carried a banner that read: “Rifles no, food yes.” “We cannot remain silent,” Barbosa said of the social calamity unfolding in Brazil.

Despite growing opposition to Bolsonaro – a right-wing radical who critics accuse of destroying Brazil’s economy, environment and place in the world – he retains a hardcore support base of about 20% of voters.

The pro-Trump former paratrooper also continues to enjoy control of congress, thanks to a deal with a powerful and infamously self-seeking coalition of centre-right parties called the “centrão”.

That support means impeachment remains an unlikely prospect unless the growing ranks of Bolsonaro’s foes can pull together to remove him from office before next October’s presidential election, which polls suggest the incumbent would lose to any of his potential challengers.

On Saturday prominent opposition leaders lined up to urge such unity.

Ciro Gomes, a centre-left former minister who intends to run for president, said Bolsonaro’s impeachment would only be possible if the opposition’s 120 representatives in congress could win over conservative allies. “Bolsonaro is a serial criminal who is attacking democracy and has killed hundreds of thousands of Brazilians,” Gomes said, before shouting: “Bolsonaro out!”

As he marched through downtown Rio, Alessandro Molon, the opposition leader in the lower house of congress, said massive street protests were crucial to show that most Brazilians now wanted Bolsonaro gone. Another major mobilisation is due to be held on 15 November.

“We have to show in the streets what the polls have already shown in numbers – that the overwhelming majority of Brazilians will no longer tolerate the misrule that has caused 600,000 [Covid] deaths and has destroyed the Brazilian economy and Brazil’s international reputation,” Molon said.

“We are occupying the streets to give visibility to the silent majority that can no longer bear Bolsonaro.”

Lyrics Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers I Won't Back Down.

Written by, Tom Petty and Jeff Lynne.

From the 1989 album, Full Moon Fever.

Well, I won't back down

No, I won't back down

You can stand me up at the gates of hell

But I won't back down

No, I'll stand my ground

Won't be turned around

And I'll keep this world from draggin' me down

Gonna stand my ground

And I won't back down

(I won't back down) Hey, baby

There ain't no easy way out

(I won't back down) Hey, I

Will stand my ground

And I won't back down

Well, I know what's right

I got just one life

In a world that keeps on pushin' me around

But I'll stand my ground

And I won't back down

(I won't back down) Hey, baby

There ain't no easy way out

(I won't back down) Hey, I

Will stand my ground

(I won't back down) And I won't back down

(I won't back down) Hey, baby

There ain't no easy way out

(I won't back down) Hey, I

Won't back down

(I won't back down) Hey, baby

There ain't no easy way out

(I won't back down) Hey, I

Will stand my ground

(I won't back down) And I won't back down

(I won't back down) No, I won't back down

Adams Cassinga. (photo: Adams Cassinga/Mongabay)

Adams Cassinga. (photo: Adams Cassinga/Mongabay)

“In DRC, to be able to prove criminality we need to be able to catch the culprits in the act — preferably as they’re about to make a sale,” Cassinga tells Mongabay from Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where he coordinates operations.

Cassinga is already awake when the call comes in at 5 a.m., the news of a tip-off hitting him like a morning shot of caffeine. Cassinga’s attention is transported to Lodja airport, little more than a small strip of exposed earth in Sankuru province, smack bang in the center of the DRC, where a suspected trafficker is planning to move a cargo of 60 African gray parrots (Psittacus erithacus) by air.

A crash course in conservation

Cassinga, now 39, founded the wildlife crime investigative nonprofit Conserv Congo in 2013, with a mission to preserve the Congo Basin’s endangered flora and fauna by combating trafficking and bringing perpetrators to justice.

Equipped with a vague notion of what conservation meant, Cassinga struggled for some time to carve out a role for himself. “I had no idea how or where to even start or what the problem even was beyond the deforestation and pollution that I had spent many years witnessing. All I knew was that I wanted to be a part of the solution rather than the problem,” he says, referring to his previous incarnation as an environmental consultant for the mining industry.

Cassinga would spend the next few years volunteering as an honorary ranger at some of the DRC’s national parks, including Lomami, Salonga, and Kahuzi-Biega; the latter just 50 kilometers (30 miles) from Bukavu, on the Congolese-Rwandan border, where he grew up, and home to some of the world’s last eastern lowland gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri).

“As I child, I could name the capitals of most countries around the world, but I knew little about the park in my backyard,” he says.

Cassinga had effectively talked his way into an unofficial two-year crash course on the front lines of conservation; inside the parks there were the rangers, whose mandates were evident enough; outside their jurisdictions, however, who was responsible for the protection of local wildlife?

“I assumed it was the job of the police, until conversations with officers revealed they didn’t believe it was their mandate to arrest poachers, despite animal protection laws. That’s when I realized there was a knowledge gap,” he says.

As a mining consultant, Cassinga had honed his skills in monitoring and evaluation through the impact assessments he provided. As a rookie conservationist, he deployed these skills to write reports and offer guidance: “I had never done law enforcement, per se, but I started writing manuals on law enforcement procedures, on surveillance and intelligence gathering,” he says.

But with a chronically underfunded (and frequently unpaid) police force, the trafficking of protected species barely registers as a priority. Cassinga soon found himself handling cases directly.

In 2017, four years after Conserv Congo was first registered, Cassinga made his first arrest, working alongside the authorities. “We learned on the job, and we made a lot of mistakes along the way,” he says. One of those mistakes was believing that once a suspect had been charged, justice would follow. Instead, it ended with the suspected trafficker bribing his way out of jail.

“We realized we couldn’t just walk away from a case, we needed to see through the legal process and find ways to counter corruption from within,” Cassinga says.

Today, Conserv Congo has a renewable five-year partnership with the state environmental agency, Congo Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN), which is overseen by the environment ministry. The NGO’s work outside of protected areas is essentially an extension of the ICCN’s mandate within the boundaries of DRC’s national parks. It also provides training to law enforcement agencies to improve conviction rates, and regularly represents the ICCN in the courts following an arrest.

Cassinga places great value in winning over the hearts and minds of the police officers he works with: “They need to understand the reason behind what we do. We have to convert them into nature lovers. They can only protect what they know and love,” he says.

Full belly versus empty stomach environmentalism

In a country where almost three-quarters of all people live on less than $1.90 a day, how do you convince people to put the interests of the environment ahead of their own hunger?

You have to help them develop the means to feed themselves, Cassinga says. “The Congo is a unique country. What is scarce elsewhere, we have in abundance. We’re one of the few countries which can rely on their natural resources in a sustainable way.”

Achieving this ecological balance, however, has remained largely elusive for many Congolese communities. Conserv Congo’s agroforestry community projects aim to remedy this by providing villagers with an alternative to poaching and deforestation, equipping them with the basic knowhow to minimize their footprint and get the most from their local habitats. Educational programs, which see the NGO visiting schools to inspire a new generation of conservationists, complement these activities.

It is this holistic approach to conservation — in particular, seeing cases through from tip-off to sentencing — that makes Conserv Congo unique. Presently, it counts five staff members on its payroll, as well as an army of full-time volunteer investigators based across the country, on whom the organization depends.

“This is not a 9-to-5 job,” Cassinga says, as he outlines the profile of a typical volunteer, many of them with day jobs.

“Of the 89 people we have this month, there’s none of us who’s above 40. Half of us can communicate in at least two different languages. Three-quarters of us have been to university. More than half of us have wives and children. We have mechanics among us, army generals, policemen,” he says.

Cassinga likens the setup to that of a newsroom: “Every investigator, just like every journalist, has a contacts book. Our investigators also have their own informants. I’m usually awake at 4:30 a.m. and everybody checks in between 5, 5:30 a.m., providing details of whatever they’re working on for that day.”

His office is his cellphone, from which he currently oversees 17 different WhatsApp groups. His description conjures up a man who is thinly stretched, juggling multiple caseloads at any one time: one colleague is instructed to keep a watchful eye on a suspect; a staff administrator is asked to transfer funds over to an investigator to cover fuel for a motorbike journey; the lawyers are busy requesting a search warrant. Limited resources force Cassinga to prioritize cases based on urgency and the likelihood of intercepting wildlife and/or making an arrest.

Cases vary in their duration; the ones that lead to an arrest can go on for months. After a tip-off, an investigator typically infiltrates a network of traffickers, sometimes going undercover as a prospective client. When enough evidence has been gathered, a raid is organized in conjunction with the authorities. Once a suspect is arrested, Cassinga’s lawyers work to ensure the rule of law is followed and that a suspect is unable to pay their way out of jail.

Cassinga was personally involved in the case of a notorious “ivory kingpin” who received a two-year sentence, following his detainment, earlier this year. “For two years, he believed I was a Senegalese citizen,” he says. “We actually became friends, we would share stories and problems … It becomes tricky.”

This conflict weighs heavily on Cassinga “every day,” and is reflected in his speech, which is suddenly punctuated with pauses. “If you don’t feel that kind of guilt you are not human,” he says.

An unconventional journey

Cassinga was a teenager during the First Congo War (1996-1997) that marked the end of Mobutu Sese Seko’s 31-year dictatorship. It was a time of deep social and political upheaval. Cassinga’s father, fearing his son would be hurt or pressed into service as a child soldier like so many others, sent him to South Africa.

Cassinga says he was 16 when he arrived there alone, and left to fend for himself in a foreign country. “I did what I had to to survive,” he says, hinting at a life of crime on the streets of Johannesburg, tempered by many hours spent in public libraries, laboriously teaching himself to speak and write in English.

Prior to leaving the DRC, “I had grown up in an environment where you were constantly told that knowledge is in the book,” he says. Those books would become his lifeline.

When he was finally granted refugee status, his language skills landed him a job with a local newspaper in Mbombela, in northeastern South Africa. As the gateway to Kruger National Park, Nelspruit (as Mbombela was then known) offered Cassinga the opportunity to report on environmental stories, as well as the mining activities that threatened to encroach on South Africa’s largest reserve. Cassinga’s journalism career came to a premature end after he was beaten, shot and hospitalized during an investigation into the death of an initiate at a local circumcision school. But, as he says, “Once a journalist, always a journalist.”

After a year spent retraining as a health and safety specialist, he traded in his low-paid, high-risk job as a journalist for a more lucrative one in mining.

“My earnings as a senior reporter were a fifth of what they were as an entry-level environmental consultant in the mining sector,” he says.

When Cassinga first took up his post, he says he naively believed he would be helping to protect the environment. Instead, the higher up the food chain he went, the less his job was about adhering to regulatory requirements, minimizing the impact on the environment, and ensuring compliance with the law, as it was about finding ways to exploit loopholes and passing the burden of responsibility on to the state. “If we were supposed to plant trees to replace those we cut down, rather than plant them ourselves we would hand over money for others to plant them, knowing that money would be spent elsewhere.” Looking back, Cassinga says his job amounted to little more than “rubber-stamping the destruction of local habitat.”

His newfound wealth and status meant these concerns did not surface until later, however.

Cassinga’s ability to speak multiple languages helped fast-track his career. After retraining in South Africa, he was sent to Ghana. He would go on to travel extensively throughout the continent.

A few years after making the transition into mining, an opportunity to return to the DRC, as a contractor, eventually presented itself.

Cassinga was 29 when he boarded a plane in the Ugandan capital of Entebbe, en route to the gold mines of Kilo-Moto in the far northeast corner of the DRC. This, he says, was the beginning of the end of his mining career.

“We flew over the forest. I’d never seen anything like it. That tropical, thick forest canopy with little rivers and rivulets crisscrossing it, that image never left my mind. Perhaps I was emotional because I had finally made it back home, perhaps it was patriotism or wanting to right the wrong, but something started talking to me,” he says of his “eureka” moment.

Cassinga witnessed new villages mushroom along the roads built for commercial mining or logging, the new arrivals cutting yet more trees down to clear farmland or make charcoal, and pushing into the newly opened forests to hunt bushmeat to eat or sell.

His experience is backed by research. Last year, a study found that the impacts of commercial logging, mining and farming in the DRC extend well beyond operational boundaries, with subsistence agriculture and illegal woodcutting often contributing to a greater loss and degradation of forests than the operations themselves.

Cassinga’s mining career eventually ran its course. “Money can buy you almost everything, but it has its limitations, it cannot buy you passion or fill a void,” he says. “I was no longer fulfilled in what I was doing.”

Two years after boarding the plane at Entebbe, Cassinga hung up his hard hat. He has no regrets about his career choices: “I have never felt any guilt whatsoever. You have to understand, all my life I had been the underdog, I’d lived on the streets. Suddenly I had money, I could take care of my family, build my mother a small house, take care of myself — I would have done anything for money,” he says.

Notwithstanding his departure from the mining industry, Cassinga is a pragmatist. “I think everything can be done responsibly — even mining,” he says. “Without mining, we’d have no roads, no hospitals, no factories. Humans depend on mining. The only problem is that in mining, we are often running against time.” And when that happens, corners get cut, he says.

It is this spirit of nonconformism, perhaps, which best defines Cassinga, whose metamorphosis from mining executive to private intelligence conservation operative defies expectations. “I am not most people’s idea of what a conservationist looks like,” he says.

Adding: “There is this myth, which is perpetuated in Africa, that anybody who’s involved in nature conservation is probably a very well-educated person with a Ph.D. or a master’s degree in science and white.”

The con in conservation

Last year, Cassinga was named an emerging explorer by National Geographic, and was awarded $10,000, which he plowed straight back into his work. However, his NGO has yet to receive a single grant, despite a proven track record in combating wildlife trafficking.

“We are mostly self-funded,” Cassinga says. From personal savings, to friends and family members and individual donations, the organization gets by in whatever way it can.

Cassinga reflects on why his NGO and others like it have found it hard to secure funding: “We are conservation outsiders. Conservation is still foreign-dominated, it’s not an African industry,” he says.

Support, to date, has typically come in the form of material resources, like boots and uniforms, and surveillance equipment, such as hidden spy cameras.

That an organization preoccupied with promoting environmental sustainability is struggling with financial sustainability is an irony that isn’t lost on Cassinga, who believes passionately that conservation shouldn’t be the preserve of the rich.

Every so often, the racket and roar of Kinshasa’s congested streets rise above our voices as motorcycles and cars jostle for an extra inch of tarmac, while pedestrians weave their way in and out of the madness. On these streets, the presence of four-wheel-drive vehicles doesn’t go unnoticed.

“I know of international NGOs with about 30 4x4s here. What do you need 30 4x4s for in the middle of the city?” Cassinga says.

“There would be foreign conservationists coming to DRC and they’d say they were there to carry out an undercover investigation, but how can you conduct an undercover wildlife investigation if you can’t even speak the language; where you stick out like a sore thumb because they can see you’re white and they’re wary of your motives? So, if these are all the challenges that you’re faced with but you’re still uncovering information, where are you getting it from? It’s because there is a smaller [local] NGO that’s doing all the hard work, but you don’t want anyone else to know about it.”

A reputation for corruption

Endemic corruption is rife in DRC, as the former mining executive turned wildlife criminal investigator repeatedly points out. To what extent Conserv Congo is a victim of its country’s reputation is difficult to say, although it might go some way in explaining why domestic nonprofits like it struggle to get the funding they need to adequately carry out their work.

In this context, it is unsurprising that the illegal wildlife trade flourishes. “Corruption is the greasing mechanism through which wildlife trafficking thrives. Without corruption, there would be almost no wildlife crime,” Cassinga says.

In August, the director-general of the ICCN, Cosma Wilungula, was ousted due to concerns about embezzlement of funds and other corruption charges. On Aug. 13, the environment ministry appointed Olivier Mushiete as his successor.

Cassinga is elated at Mushiete’s appointment as the head of the DRC’s primary environmental protection agency. He says Mushiete has impressive agroforestry credentials: “I love it. Change is good sometimes. Change is positive.”

Over the years, Cassinga has found a way to clear a path for Conserv Congo through the jungle of corruption that plagues the country; with Mushiete at the helm, he has renewed hope for Congolese conservation and the new opportunities his leadership will bring.

Back in Lodja, it’s noon by the time the legal team have liaised with magistrates and secured a search warrant, leading to the arrest of two men, including the owner of a freight company. Two crates of 30 African gray parrots each are seized and Cassinga’s team is already busy working on sending them to a place of safety. In Kinshasa, the improvised raid sends an adrenaline rush coursing through Cassinga’s veins, making him lose his appetite — an occupational hazard.

“Everything we work towards is for this. To suddenly get this result, even though we did not expect or plan for this,” Cassinga says, not quite believing his luck. Although luck is only part of the equation: “Sometimes, these are like barometers which measure and reflect how much work you’ve put in.”

However, when Mongabay checks back in, a few days later, lady luck has thrown Conserv Congo a curveball, underscoring what conservation in DRC is up against: the NGO has unwittingly stumbled on a large trafficking network involving officials at the Ministry for Environment.

“We have always suspected that officials were involved in issuing permits and facilitating the movement of these birds, but we never had a ‘hand in the cookie jar’ moment — until now”, Cassinga says. The two suspects caught, it turns out, “are just the tip of the iceberg”, and under interrogation, they have given up the names of those involved.

“We are finding out who issues the documents, who facilitates the entry into the airport, and we’re following the tracks. One by one they are being called to appear before the courts. They range from simple permit-authorizing officials from the department, to policemen, to the military”, he adds. “It is a whole network of traffickers and we aim to dismantle it”.

A deflated Cassinga also delivers the news that half the parrots have succumbed to either death or theft. “The court returns the birds to us, after reviewing the ‘evidence’, but we can’t move them without permission,” says Cassinga. “The parrots in the cages contaminate each other with whatever diseases one of them might have; they die.”

Funding setbacks and a kafkaesque bureaucratic nightmare cause further delays. In a small village, with substandard infrastructure, a robbery is easy to pull off: There is a break-in.

“It is tormenting, I am hyperventilating. I’m just too emotional to even talk about it, it’s a lot of work and sometimes it’s tiring and if you don’t have a strong heart, sometimes you feel like giving up,” Cassinga says.

“But if we give up, what is going to happen?”

This article was originally published on Mongabay.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment