Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

In June of this year, India Walton shocked the political world by defeating the four-term incumbent mayor of Buffalo, Byron Brown, in the Democratic primary, setting the table for her to become the favorite to win the Mayoral race in November because it’s a heavily Democratic city.

She would be the first democratic socialist to be elected mayor of a major American city in more than half a century, and the first woman — and first Black woman — to lead New York’s second-largest city. India Walton is a registered nurse, a union member and organizer, a community activist, a single mother of 4 boys — and come November, we’ll start addressing her as “Mayor.”

Of course, the corporate Democratic establishment only knows how to fight like hell when they are punching left - so India is now facing a barrage of attacks, personal threats, and a write-in campaign from the man she already defeated in the Democratic primary. And it is being funded and supported by some Republicans and Trump-aligned figures.

The general election is next month, on November 2nd. We must all circle-the-wagons and support India Walton in any way that we can. You can also help by listening to her story in this week’s episode of Rumble with Michael Moore and sharing it with others.

Just listen to India Walton’s conversation with me and hear how it’s done.

-Mike

[listen at MichaelMoore.com or on Spotify, Apple, etc]

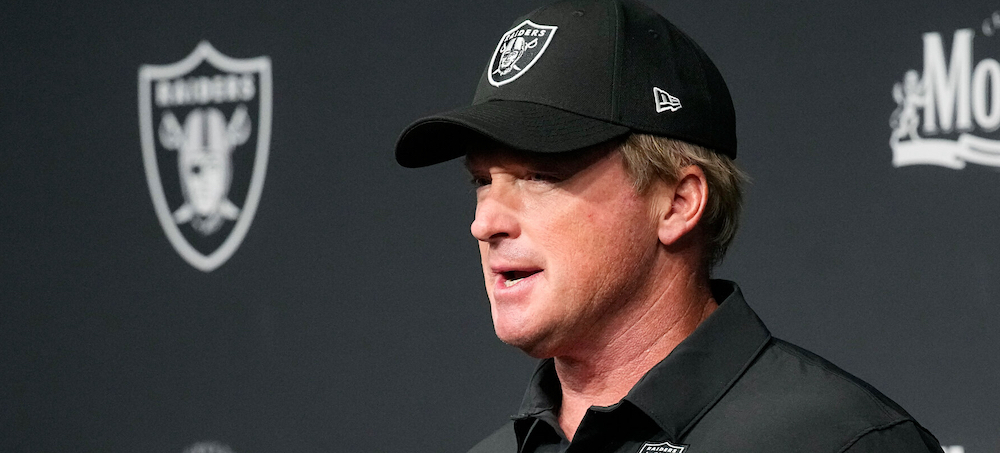

Jon Gruden. (photo: Rick Scuteri/AP)

Jon Gruden. (photo: Rick Scuteri/AP)

"I have resigned as Head Coach of the Las Vegas Raiders," Gruden said in a statement. "I love the Raiders and do not want to be a distraction. Thank you to all the players, coaches, staff, and fans of Raider Nation. I'm sorry, I never meant to hurt anyone."

Among the targets for Gruden's insults were DeMaurice Smith, executive director of the NFL Players Association, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell and then-Vice President Joe Biden.

The emails emerged from an investigation into workplace misconduct at the Washington Football Club. The offensive terms were used in emails sent from Gruden to former Washington team president Bruce Allen and others. Allen was fired in 2019.

Gruden sent the emails between 2011 and 2018, while he was a color analyst for ESPN's Monday Night Football. Before joining ESPN, Gruden coached the Raiders and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

The existence of racially disparaging emails were first reported on Friday by The Wall Street Journal. On Monday evening, The New York Times reported on emails that included homophobic and misogynistic comments.

Gruden, 58, signed a 10-year, $100 million deal with the Raiders in 2018. By Monday evening, the Raiders had already removed Gruden's profile from the team's website.

Steven Mnuchin. (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

Steven Mnuchin. (photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

President Donald Trump very much wanted Ivanka at the helm, and it was the Treasury secretary who blocked her ascent.

As the White House moved to select its new leader, one name very dear to Trump’s heart kept floating around: his daughter Ivanka Trump. That never came to fruition, though, with Ivanka later telling reporters that though her father had raised the subject, she declined to pursue the position as she was “happy with the work” she was doing as his senior adviser.

Ivanka Trump did, however, aid Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin and White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney in the selection process. When the Treasury Department announced Under Secretary of the Treasury for International Affairs David Malpass as the World Bank’s new president, Ivanka released a statement predicting Malpass would be “an extraordinary leader of the World Bank.” (Malpass was in fact a controversial pick, due in large part to his past criticisms of the World Bank.)

But two sources, not authorized to speak publicly, tell The Intercept the talk of Ivanka at the helm went far beyond the realm of Beltway chatter: Trump very much wanted Ivanka as World Bank president, and it was Mnuchin who actually blocked her ascent to the leadership role.

“It came incredibly close to happening,” said one well-placed source.

Representatives for Mnuchin and Ivanka Trump did not respond to requests for comment, nor did the World Bank or the Trump Organization.

Since the World Bank’s creation in 1944, the U.S. has always led the prerogative to name the bank’s president in an informal agreement with European leaders, who are given the job of naming the head of the International Monetary Fund (an arrangement that rather bluntly underscores the Western imperial nature of the international financial institutions).

Prior to her role at White House adviser, Ivanka spent 12 years at the Trump Organization as executive vice president of development and acquisitions. She also launched her own line of fashion products which, according to 2019 financial disclosures, reportedly brought in between $100,000 and $1,000,000 in rent or royalties.

Once in 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, Ivanka helped launch the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative, colloquially known as the “Ivanka Fund”: a World Bank-supported project to raise money for female entrepreneurs in developing nations. It was her work on the Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative that White House spokesperson Jessica Ditto cited in explaining Ivanka’s qualification for selecting the next World Bank leader. “She’s worked closely with the World Bank’s leadership for the past two years,” Ditto said.

But that initiative still left her pretty light on experience. “That’s a very thin base to try to establish credibility in this multilateral institution,” said Scott Morris, director of the U.S. development policy program at the Center for Global Development in D.C. “It’s hard to imagine that she would have been viewed as a credible leader. It would be the worst kind of exercise of U.S. power. I have to think as a candidate she would have encountered some resistance. But maybe [the bank’s members] would not have wanted to provoke the U.S. president.”

From the moment her father won the presidential election, Ivanka has been wrapped up in controversy: She falsely testified that she was uninvolved in the 2017 inauguration (a lawsuit alleged that the Inaugural Committee overpaid for event space at the Trump International Hotel in D.C.); she and her husband, fellow presidential adviser Jared Kushner, earned hundreds of millions in outside income while working in the White House; and her Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative was ultimately a flop.

Mnuchin often placed himself between the president and what the Treasury secretary saw as colossally counterproductive moves. His time as a Hollywood producer — making him a representative of the set whose approval Trump craved — gave him influence that others in the administration lacked. He pushed Trump to name Jerome Powell as head of the Federal Reserve and routinely talked him out of random government shutdowns. His successful effort to talk Trump into backing and signing the CARES Act was among his other significant achievements. He also had a habit of dodging responsibility for Trump’s worst excesses. On January 6, he made sure that he was in Sudan.

But given that there’s a growing discontent among the World Bank’s member nations over the U.S.’s unilateral ability to nominate the institution’s leadership, the Ivanka saga could serve as a warning against the status quo. “A growing number of countries don’t like this whole arrangement,” said Morris. “For them to hear how close it was to being the U.S. president’s daughter probably adds fuel to the fire that the Americans are so cavalier about this.”

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

Donald Trump. (photo: Getty Images)

“That was the advice that one person in the Justice Department was suggesting — but just one person. And [Trump] rejected all that,” Grassley told Newsmax of Justice Department official Jeffrey Clark’s gambit to get state legislatures to designate new electors. “And they’re trying to make it a scenario [where] he was trying to get the Justice Department” to get alternate electors.

We’ve already laid out the huge problems with this defense — most notable among them being the implication that Trump backed off the scheme for moral reasons. (The reasons were clear: It wasn’t going to work.)

But another aspect of this hasn’t been explored enough. And that’s this: the sheer desperation and ridiculousness of what undergirded this entire effort.

An interim Senate Judiciary Committee report released Thursday showed this effort revolved around some of the most specious conspiracy theories at the Trump team’s disposal — theories that in several cases had already been debunked and in every case didn’t pass the smell test.

On Dec. 27, Rep. Scott Perry (R-Pa.) contacted acting deputy attorney general Richard Donoghue at Trump’s behest. Perry proceeded to share a few theories with Donoghue, including that there were 205,000 more votes than voters in Pennsylvania and that more than 4,000 Pennsylvanians voted twice.

The same day, Trump called acting attorney general Jeffrey A. Rosen and offered both the former theory — about more votes than voters in Pennsylvania — and a theory that video from State Farm Arena in Atlanta “shows fraud” by election workers who counted ballots hidden under a table multiple times.

The theory about State Farm Arena had already been debunked extensively weeks earlier (indeed it was one of the most talked-about and debunked theories). The 4,000 voters-voting-twice theory came from matching first names, last names and dates of birth in voting records, but this too had been debunked as a fraud-finding method in the weeks prior.

As for the idea that there were more votes than voters (here’s what Perry sent Donoghue)? This was also pretty easily explained — and was just as quickly debunked. While there were nearly 7 million votes cast, a system used by the Pennsylvania secretary of state, called the Statewide Uniform of Registered Electors (SURE), recorded only 6.8 million voters at the time. The reason: The SURE data lagged, because it involved manually entering records about people’s voter histories.

The gap was due to incomplete data in multiple counties, but mostly in Pittsburgh-based Allegheny County, which accounted for 120,000 votes of the approximately 200,000-vote gap. How do you know the data was, in fact, incomplete? Because at the time, it would have meant the turnout rate in Allegheny County was less than 64 percent of registered voters, while statewide it was 76 percent. That doesn’t make any sense.

What’s more, it was clear that such data could lag, because even those pushing the theory acknowledged it:

Even the state GOP lawmakers’ news release notes that “three small rural counties have not fully posted results online” and that, thus, the totals aren’t complete. Why not allow for the possibility of other data also being incomplete, particularly data involving extensive voting histories?

Closer to the turn of the year, White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows began barraging DOJ officials with yet more theories. Here’s a look at what they were, and when they were debunked (in parenthesis):

- That 66,247 underage voters had unlawfully cast ballots in Georgia (debunked by GOP-run Georgia secretary of state’s office Dec. 23)

- That thousands of votes were unlawfully cast by individuals registered at P.O. boxes or who didn’t live in the area where they voted (debunked on Dec. 10 and Dec. 14)

- That the election was stolen using satellites in Italy (debunked in early January)

- That GOP poll watchers in New Mexico were not allowed to observe, and that late-night vote dumps suggested malfeasance (rejected by state Supreme Court in November, debunked in November, Trump lawsuit abandoned in mid-January)

One thing to keep in mind in all of this is that these weren’t just theories the White House and its allies were floating for public consumption; these were the things they used to try to convince seasoned, smart lawyers at the Justice Department that their claims had merit — merit enough to get the Justice Department to call the election results into question.

The theories were bad enough that Donoghue and Rosen privately derided them in their then-private correspondence:

When then-acting attorney general Jeffrey A. Rosen shared the email from Meadows with Donoghue, Donoghue responded, “Pure insanity.”

About an hour later, Meadows shared previously debunked claims about “signature matching anomalies in Fulton county, Ga.”

“Can you believe this?” Rosen wrote to Donoghue. “I am not going to respond to the message below.”

Donoghue responded: “At least it’s better than the last one, but that doesn’t say much.”

It is indeed a veritable smorgasbord of what the dregs of the Internet and extreme figures in the GOP had to offer on this stuff. But given that so many of the Trump team’s claims had been rejected in courts and otherwise debunked, this was apparently what they had to work with when the clock was ticking toward midnight and they badly needed an assist from DOJ.

It all can perhaps be best summed up by a Trump quote that Donoghue jotted down in his notes from their Dec. 27 meeting: “You guys are not following the internet the way I do.”

That much was certainly true.

Texas governor Greg Abbott. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/The Texas Tribune)

Texas governor Greg Abbott. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/The Texas Tribune)

Greg Abbott’s move comes as Biden administration set to issue federal vaccine rules for employers with more than 100 workers

The move comes as the Biden administration is to issue rules requiring employers with more than 100 workers to be vaccinated or test weekly for the coronavirus. Several major companies, including Texas-based American Airlines and Southwest Airlines, have said they would abide by the federal mandate.

“No entity in Texas can compel receipt of a Covid-19 vaccine by any individual, including an employee or a consumer, who objects to such vaccination for any reason of personal conscience, based on a religious belief, or for medical reasons, including prior recovery from Covid-19,” Abbott wrote in his order.

Abbott, who was previously vaccinated and also later tested positive for Covid-19, said in his order that “vaccines are strongly encouraged for those eligible to receive one, but must always be voluntary for Texans”.

Abbott previously barred vaccine mandates by state and local government agencies, but until now had let private companies make their own rules for their workers. It was not immediately clear if Abbott’s latest executive order would face a quick court challenge.

Abbott’s new order also carries political implications. The two-term Republican is facing pressure from two candidates in next year’s GOP primary, former state senator Don Huffines and former Florida congressman and Texas state party chairman Allen West, have attacked Abbott’s Coovid-19 policies and have strongly opposed vaccine mandates.

“He knows which the way the wind is blowing. He knows conservative Republican voters are tired of the vaccine mandates and tired of him being a failed leader,” Huffines tweeted.

West announced this this week he tested positive for Covid-19 and has been hospitalized, but also tweeted he remains opposed to vaccine mandates.

Texas has seen a recent decrease in new Covid-19 cases and hospitalizations. But a rising death toll from the recent surge caused by the delta variant has the state rapidly approaching 67,000 total fatalities since the pandemic began in 2020.

Members of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) take part in a demonstration against then governor Ulises Ruiz in November 2006. (photo: Alfredo Estrella/Getty Images)

Members of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO) take part in a demonstration against then governor Ulises Ruiz in November 2006. (photo: Alfredo Estrella/Getty Images)

The southern Mexican state of Oaxaca is known for its tradition of left political militancy. And its indigenous people have often been at the vanguard of that struggle.

In a new book, historian A. S. Dillingham narrates the prehistory of that explosive moment, focusing on the role of bilingual indigenous teachers in the Oaxacan teachers’ union throughout the twentieth century. Oaxaca Resurgent: Indigeneity, Development, and Inequality in Twentieth Century Mexico reveals the rich tradition of indigenous militancy and trade union struggle in Oaxaca.

Oaxaca Resurgent is the culmination of more than a decade of research, and Dillingham’s sources range from oral histories shared by trade union militants to secret documents produced by the Mexican security state. Against commonplace narratives of political acquiescence in Oaxaca, it reveals “a different history, a history in which questions of cultural liberation and social transformation were intimately linked,” as Dillingham writes in the book’s introduction.

In this conversation with Jacobin’s Jonah Walters, Dillingham describes the rich history of indigenous and trade union militancy in Oaxaca — including the 2006 movement, which some compared to the Paris Commune.

JW: When you set out to write Oaxaca Resurgent, did you think of it as a labor history or a history of indigenous political movements in Oaxaca?

ASD: I thought of it as a prehistory of a particular strike.

In 2006, I enrolled in a graduate seminar that took place annually in Oaxaca City. The seminar was interrupted by a massive teachers’ strike. It began as a traditional May Day strike, something Oaxacan teachers had engaged in since 1980. But that year, Governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz chose to brutally repress it.

A large social movement blossomed in support of the teachers. Walking around Oaxaca City in 2006, when activists controlled much of the city center, it became clear to me that I was witnessing a vibrant and historic social movement. Some people have even compared it to the Paris Commune of 1871. How did it emerge? The book began as an attempt to answer that question.

The teachers’ union in Oaxaca is the largest trade union in the state, with roughly seventy thousand members in 2006 and a range of political currents contained within it. As I talked to Oaxacan activists and intellectuals, a number of people encouraged me to look at the role of Indigenous bilingual teachers in the union, even arguing that they acted as a kind of militant vanguard for the movement as a whole.

Because I came to focus on those bilingual teachers — who are bilingual in Spanish and one (or more) Indigenous languages — I had to think deeply about the history of indigeneity in Oaxaca. This led me to examine a broader ideological project in Mexico called indigenismo, or “indiginism,” which became another key focus of the book.

ASD: In the nineteenth century, Mexican elites succeeded in liberating themselves from Spanish control. And after independence, one of the ways they tried to distinguish themselves from their former European colonizers was by invoking the pre-Hispanic past. This was also true well beyond Mexico: romantic invocations of a pre-Hispanic Indigenous past characterized elite discourse in nearly all the former Iberian colonies in the Americas.

The Mexican Revolution was one of the great social revolutions of the twentieth century, taking place roughly contemporaneously with the Russian Revolution of 1917. And because the revolution involved the mass participation of ordinary people, it brought Mexico’s Indigenous population, which is quite large and diverse, into the public light. This prompted a shift in elite ideology.

In the postrevolutionary period, a new state discourse coalesced that celebrated the Indigenous past while frequently marking living Indigenous people as barriers to modernization or progress. Even some left-wing intellectuals participated in a version of this discourse, identifying Indigenous people as barriers to the kind of class politics represented by peasant federations and trade unions.

But the official discourse of indigenismo never went without a response by people marked as Indigenous. There was a contradictory dynamic within indigenista politics, which in the book I call “the double bind of indigenismo.” Indigenismo rhetorically celebrated Indigenous people, but it also cast them as a problem to be overcome. For that reason, and perhaps counterintuitively, it sometimes proved valuable for Indigenous social movements, because they could use its vocabulary to make various demands on the state.

JW: What kind of place is Oaxaca?

ASD: Oaxaca, which is in southern Mexico, is today one of the poorest states in the country. But in the colonial period, when Mexico was New Spain, Oaxaca was a center of commerce and wealth. It was the center of an Indigenous population that maintained its own hierarchies and leaders, and which was able to negotiate with Spanish intermediaries to sustain several very successful industries, including silk and cochineal (a bug that creates a red dye).

Oaxaca became a center of colonial prosperity because of its varied topography — multiple mountain ridges, high-altitude valleys, a Pacific coastal plain. Microclimates in Oaxaca allowed for self-sufficient regional economies that could together buoy a large population. But with the increasing nationalization of the Mexican economy in the twentieth century, those same advantages became disadvantages.

The mid-twentieth century saw the rise of commercial agriculture, and Oaxaca’s topography did not fit with that model of capitalist development. Oaxaca did become increasingly integrated into the national economy, but that integration took the form of mass migration out of the state, as Oaxacans sought seasonal wage labor in other parts of Mexico and beyond. Today there’s a veritable Oaxacan diaspora that spans the continent.

JW: As you point out, at the very moment that economic modernization was devastating Oaxaca, there was a wave of academic interest in the supposedly backward or primitive ways of indigenous people there. How has that kind of elite attention contributed to the politics of the place?

ASD: I begin Oaxaca Resurgent with a story about a group of people in a Triqui community on the western edge of the state. In 1899, this community encountered an early anthropologist named Frederick Starr, who was traveling throughout Central America and southern Mexico attempting to photograph and measure the heads of various Indigenous peoples.

In Starr’s travel journals, I discovered the story of a group of Triqui women and girls who refused to be measured or photographed. They fled the town market where they had been selling their wares and were chased down by Starr and his assistants. Starr’s team eventually captured the women and forcibly measured them; I found their photographs in a research library in Oaxaca.

This story is a reminder that to chart the trajectory of a politics of representation for Indigenous people in Mexico, you must also consider the ways Indigenous peoples have refused representation, whether by the state or anthropologists.

By the mid-twentieth century, Mexico saw the rise of development thinking — what people sometimes call modernization theory. Applied anthropologists working on development programs tried to solve the “problem” of bringing Indigenous regions into the national economy and the nation-building project it represented. Predictably, in Mexico, Oaxaca was a site of much academic and government interest in thinking these questions through.

Some of those anthropologists and development workers were well-meaning left intellectuals. But even when they wanted to uplift these regions marked as unintegrated or impoverished, they often ended up equating poverty with indigeneity. Rather than confronting more structural issues, they ended up talking about the supposed need to change the behaviors of the poor. They thought these populations were poor because they didn’t speak the national language (Spanish), or because they were too tied to cultures and customs and traditions, or that they spent too much money on saints’ day festivals (which are essentially annual block parties).

At the same time, while there was that top-down dynamic, many of these development projects required local brokers to implement them successfully. Development agencies had to contract local “extensionists” who were fluent in Indigenous languages to serve as bridges between federal policies and local communities.

In the book, I follow how those local development workers, those bilingual “promoters,” became politicized and radicalized, oftentimes through their own frustrations with government efforts, which led them to develop alternative proposals for Indigenous development.

JW: What is the history of teachers’ unionism in Oaxaca?

ASD: As I mentioned before, Mexico created a new state in the aftermath of the revolution. In 1917, it ratified one of the most radical constitutions in the world, which guaranteed labor rights, including the right to join a trade union, as well as other social rights that far exceeded those enumerated in the eighteenth-century constitution of the United States.

The revolution was followed by a civil war that lasted ten years. The postrevolutionary state built itself, or rather reconstituted itself, through mass organizations, such as peasant federations and trade unions. For most of the twentieth century, the teachers’ union in Mexico — the National Union of Education Workers (SNTE) — was an instrument of state policy. It was also often a way for individuals to move up the political ladder of the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI).

One of the guarantees of the 1917 constitution was free secular education for all Mexicans. This meant that state actors eventually had to start reckoning with the diversity of the country itself — especially in terms of education policy. In the first half of the twentieth century, the Ministry of Education accomplished this by contracting auxiliary teachers — or bilingual “promoters” — to help facilitate Spanish language acquisition in the classroom. By the 1960s, many of the people who had been contracted as auxiliary teachers or bilingual promoters started to make demands to become fully trained federal teachers.

They wanted to be designated as federal teachers because then they would have access to the union, and through the union receive better pay and benefits. But this was also an anti-racist struggle to respect and value Indigenous educators as equal to the traditional federal teacher, who had prestige. They eventually won by the mid-1970s, and at that point those bilingual teachers were incorporated into the teachers’ union in Mexico.

Bilingual teachers brought with them an experience of political mobilization and radical politics, and allied with other reformers who wanted to democratize the union by taking control away from PRI leaders. Indigenous bilingual teachers ended up playing a crucial role in the fight to democratize the teachers’ union and the fight against austerity, which was on the rise in Mexico.

By the late 1970s, Mexico was participating in the US-led “war on drugs.” The Mexican government was conducting anti-narcotics raids in which they fumigated marijuana and poppy fields throughout southern Mexico. I found declassified state records that documented a counter-narcotic raid in Oaxaca in 1977 — in this case, the Mexican army and judicial police landed in a rural town and ended up detaining a principal and two teachers from a local primary school. This was because dissident teachers in Oaxaca were increasingly speaking out against the PRI. It was clear to me that security agents were more concerned about dissident teachers than drug production or trafficking.

State repression in Oaxaca connected to the drug war was a major contributor to the general dissatisfaction that, much later, found expression in the teachers’ strike and related social movement in 2006.

In 2006, Oaxacans established a mass social movement organization called Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO). This was basically an umbrella coalition that included representatives of the teachers’ union, but also members of other social movements, progressive Catholic organizations, radical urban youth, and nonprofits active in progressive causes. The APPO brought all these people together in a movement not just to address the education question but to transform politics in Oaxaca writ large.

It was the combination of national political calculations and brutal repression that put an end to the Oaxacan movement in 2006. Federal police, which are basically a militarized police force, were brought in. Some came on a highway from Mexico City and others arrived on planes, and they launched a siege to take control of Oaxaca City.

We know now that the Oaxacan governor also used escuadrones de la muerte, “death squads.” Unmarked vehicles full of ununiformed, armed men seized activists off the road to torture or disappear them. Many ended up in federal jails across the country. And in that movement’s wake, there was a massive escalation of violence and militarization all around Mexico.

JW: You consulted a wide range of archives in your research. But I understand you looked at Mexican state security archives in particular. What did you learn from those sources?

ASD: Mexico had its own equivalent of the United States’ FBI, which was the Federal Security Directorate (DFS). This was a state espionage agency, which during the second half of the twentieth century spied on everyone from dissident teachers to peasants to anthropologists who worked for government agencies, even high-ranking political officials and federal functionaries.

The records of the DFS were classified until the presidency of Vicente Fox in the early 2000s. Around 2008 or so, together with other historians, I began opening those boxes. The files are held in the national archives in Mexico City — a converted Porfirian prison called Lecumberri.

These security files ended up being an important source base for me, because state officials were keeping tabs on dissident teachers and anthropologists and others involved in Indigenous politics.

Obviously, one has to read files like that with a critical eye, because security agents often overstate threats. I compared what I learned in those files to the conversations I was having with retired teachers and government bureaucrats. In that way, I could cross-reference the security files with oral history. It was also nice to turn government spying around and use it to critique the state and tell a story of grassroots activism.

Unfortunately, during the presidency of Enrique Peña Nieto [2012–2018], access to those files was effectively closed. Now there’s an uphill battle for people who are interested in studying twentieth-century Mexico, especially topics related to the dirty war or the Cold War. The state has highly restricted the public’s ability to look at those files.

JW: How do you understand the relationship between indigeneity, neoliberalism, and multiculturalism?

ASD: The multicultural turn at the end of the twentieth century was a moment of historical contingency that I think we’ve failed to fully appreciate. When I look at the rise of multiculturalism, I don’t just view it as a top-down project — elites and their savvy technocrats duping us all. Instead, I locate its origins historically, from the bottom up. I think this is a history we should try to keep in mind as we imagine a better future.

On the Left, people have long had a healthy skepticism of neoliberalism and the rise of multicultural frameworks. That’s why many left and Indigenous activists have denounced these multicultural gestures as superficial and hollow — a way for powerful actors and institutions to superficially celebrate cultural difference without considering ongoing inequalities.

I sympathize with that position deeply, but I think it gives a bit too much power to the idea that neoliberalism has successfully defeated all forms of resistance. People sometimes argue that multiculturalism is the cultural logic of late capitalism without acknowledging that many multicultural policies — such as bilingual education in Mexico or ethnic studies in the United States — resulted from the demands activists were making, in the 1970s in particular.

The New Left in the late 1960s, and even more so in the 1970s, produced its own forms of cultural pluralism. New Left activists in Mexico and beyond tried to think about how to connect a politics of liberation, a politics of revolution, with the particular experiences of the marginalized communities they found themselves in. For many of these activists, the struggle against material inequality was linked to struggles around racism and cultural liberation.

Neoliberalism has effectively delinked those struggles. But that’s not because they’re inherently contradictory. Unfortunately, on the Left, you sometimes encounter people who tacitly accept that delinking, and say that to recognize the political value of cultural pluralism is to somehow not take class inequality seriously. But this is a poor form of revolutionary politics we need to move beyond.

How might we imagine more egalitarian and reciprocal forms of articulating our politics — and ultimately reorganizing society? I think there are lessons the international left can learn from the kind of political radicalism that emerged in Oaxaca in the 1970s.

To understand the global history of the Left, it’s worth looking closely at how Indigenous activists engaged with and transformed Marxism. In places like Oaxaca, radicals strove to understand how Marxism as a theory of emancipation could inform the experiences of their own communities, which oftentimes operated (and still do, to this day) under communal structures (usos y costumbres) through which people have both rights and obligations to the broader community.

Oaxacan intellectuals and activists developed a particular kind of theory in response to these questions — comunalidad, or “communality.” There are different versions of comunalidad, but it is generally concerned with transposing the mutual-aid dynamics of Indigenous communities onto a national or global scale. Rather than a society based on individuals and personal profit, comunalidad posits a society based on community, reciprocity, and mutual aid. It’s a tradition that has been overlooked that I think speaks to many of the pressing concerns of our world today.

A gray wolf. (photo: National Geographic)

A gray wolf. (photo: National Geographic)

The Idaho Department of Fish and Game late last month entered into an agreement with a nonprofit hunting group to reimburse the expenses for a proven kill.

The agreement follows a change in Idaho law aimed at killing more wolves that are blamed for attacking livestock and reducing deer and elk herds. Montana this year also expanded when, where and how wolves can be killed.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, at the request of environmental groups concerned about the expanded wolf killing in the two states, last month announced a yearlong review to see if wolves in the U.S. West should be relisted under the Endangered Species Act.

Idaho has managed wolves since they were taken off the list in 2011. State wildlife managers had been incrementally increasing wolf harvest during that time, but not fast enough for lawmakers, who earlier this year passed the law backed by some trappers and the powerful ranching sector.

Idaho Fish and Game Director Ed Schriever told lawmakers on the state Natural Resources Interim Committee during an informational meeting last month that the agency has been carefully tracking wolf kills.

“It is my opinion that they (U.S. Fish and Wildlife) will be looking at the change in harvest in Idaho over the next 12 months and looking at the components of that, and if there is a large change, and if it can be attributed to a change in regulatory mechanisms, that might be of considerable interest to them,” Schriever told lawmakers.

“I don’t think this thing is going to jump off of the rails, but I will assure you we are watching this very closely,” he said.

Schriever told lawmakers that wolf mortality through early September has not had a big spike compared to previous years. The new law took effect on July 1.

Idaho is also facing a potential lawsuit concerning the possible killing of federally protected grizzly bears and lynx due to the new law. Another environmental group has asked the U.S. Forest Service to protect wolves in wilderness areas in the two states from professional contract hunters and private reimbursement programs.

Idaho Republican Gov. Brad Little earlier this year signed the measure lawmakers said could lead to killing 90% of the state’s 1,500 wolves before federal authorities would take over management. Schriever said a new wolf population estimate will be available in January.

The $200,000 to pay for the reimbursement program is coming from licenses and fees paid by hunters to Fish and Game. That money will then be distributed by the state's Wolf Depredation Control Board in the agreement with the Foundation for Wildlife Management, a hunting group that describes its mission as protecting deer and elk herds.

According the group's website, the reimbursement program pays $2,500 for killing a wolf in an area where Fish and Game says wolves are chronically preying on livestock. The agency defines that as areas where at least one confirmed or probable livestock depredation has occurred each year for five years.

The group is paying $2,000 per wolf in hunting units where Fish and Game says predators are keeping elk from meeting management objectives. Hunters will get $1,000 per wolf in the northern tip of the state, and $500 elsewhere. The group notes reimbursements will be cut significantly if the money starts running out before June 2022.

Most of the high-dollar reimbursements are in central and west-central Idaho, and include designated wilderness areas.

Justin Webb, the group's executive director, didn't return a call from The Associated Press.

“This bounty system for wolves is one of the things that would contribute to the relisting of wolves,” said Jonathan Oppenheimer of the Idaho Conservation League, one of the groups that requested federal officials consider relisting. “This was a foreseeable consequence that the Fish and Wildlife Service would take a close look at some of the changes that were made.”

Besides setting up the reimbursement program, the new law also expands killing methods to include trapping and snaring wolves on a single hunting tag, no restriction on hunting hours, using night-vision equipment with a permit, using bait and dogs, and allowing hunting from motor vehicles. It also authorizes year-round wolf trapping on private property.

In Montana, state wildlife authorities approved a statewide harvest quota of 450 wolves, about 40% of the state’s wolf population. Methods for killing wolves that were previously outlawed can now be used. Those include snaring, baiting and night hunting. Trapping seasons have also been expanded.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment