Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Manchin, the Democratic senator from West Virginia — whose vote is essential given scorched-earth Republican opposition to anything Biden might propose — is reportedly against the Clean Energy Payment Program, the core of Biden’s attempt to take action on climate change, and wants to impose work requirements on the child tax credit, a key element in plans to invest in the nation’s children.

You might be tempted to view this impasse as an indictment of America’s wildly unrepresentative political system, which effectively allows the interests of a small state — West Virginia has substantially fewer residents than the borough of Brooklyn — to dominate national concerns. But it’s actually worse than that: Manchin appears ready to veto policies that would be in the interests of his own constituents.

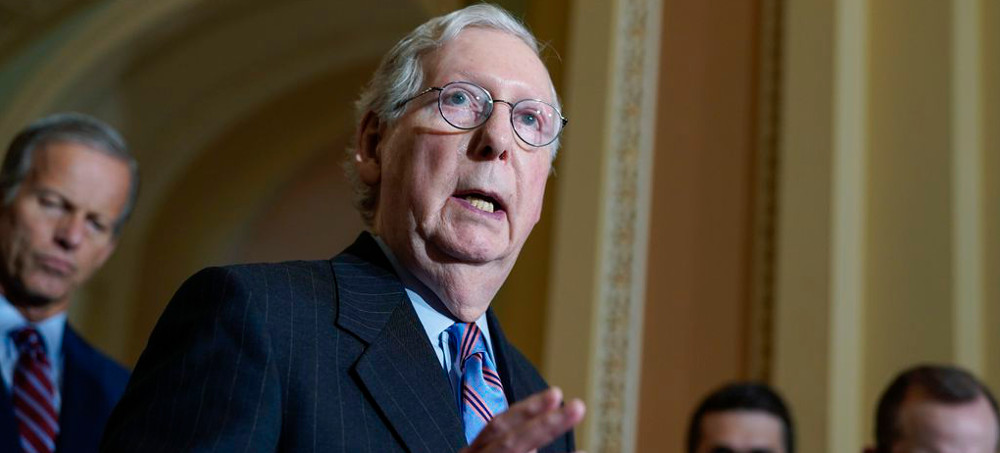

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell spoke to reporters after a Republican strategy meeting at the Capitol on Tuesday. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell spoke to reporters after a Republican strategy meeting at the Capitol on Tuesday. (photo: J. Scott Applewhite/AP)

Democrats are ready for the GOP to stonewall their massive voting-rights bill. It’s the next fight over the filibuster that really matters

Original story below.

It’s not often the leader of the United States Senate holds a vote knowing it will fail. It’s even less often that the Senate leader calls a doomed vote for one of the most important bills in his party’s legislative agenda.

Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) is about to do just that. The Senate will vote Wednesday on the Freedom to Vote Act, a once-in-a-generation bill to safeguard the right to vote, disclose dark money, and stop the partisan operatives who tried to steal the last election from stealing the next one. The vote is almost certainly going to fail. Democrats hold 50 seats, they need 60 votes to beat a Republican filibuster, and there’s no indication that even one GOP senator, let alone 10, plans to break ranks and support the bill.

But for the Democratic lawmakers and outside activists pushing the bill, failure on Wednesday’s vote isn’t just expected — it’s part of the plan. They say it’s one of the final steps in a years-long, carefully choreographed strategy, one more proof point that Republicans won’t support even the most popular voting-rights and clean-government reforms.

And if not a single Republican will vote for those reforms, then Democrats have no choice but to negotiate a change to the filibuster rules that will allow them to pass the Freedom to Vote Act and try to shore up America’s battered democratic system in time for the 2022 elections.

Even with years of planning, the odds are long they pull it off. They have to win over centrist Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) and rogue Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.), not to mention half a dozen other senators who’ve privately expressed doubts about changing the filibuster. But those close to the action, the congressional aides and activists on the inside, believe this is their moment.

A Tidal Wave of Lies

The timing of tomorrow’s vote — and the even more critical fight to follow — couldn’t be more urgent. From January to September, 19 states have passed 33 new laws that will make it harder to vote and easier to sabotage elections, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. Some of these laws seek to reduce the number of polling places available to voters and limit the number of hours for early voting. Some of these laws reduce the window of time available to apply for a mail-in ballot and minimize the number, location, and availability of dropboxes in which you can safely submit your mail-in ballot. Some of these laws increase criminal penalties for local election workers who try to assist citizens in exercising their right to vote, whether it’s giving out water or snacks to voters waiting in line, helping voters with disabilities turn in their ballots, or encouraging voters to request mail-in ballots.

Those are the only bills that have become law. According to the Brennan Center, more than 425 bills that include measures to restrict voting access have been introduced in 49 states this year. To be sure, there are state lawmakers pushing to improve voting rights at the state level, with at least 25 states passing 62 laws in 2021 that would help expand voting access.

But Daniel Weiner, a voting-rights expert at the Brennan Center, says the wave of voter-suppression laws this year is an unprecedented assault on access to the ballot box, driven, in large part, by Republican legislatures acting on former President Donald Trump’s baseless claims about a stolen election. “A lot of it has been driven by falsehoods about the 2020 election, particularly around things like vote-by-mail,” Weiner says.

Soon after winning control of the House, Senate, and White House earlier this year, the Democrats came out with the For the People Act, their answer to the growing assault on voting and democracy by Trump-inspired GOP lawmakers. The For the People Act was like the pot roast of progressive politics: A doorstop of a bill, Democrats had grabbed every reform idea they had in the cupboard and tossed it in the bill — combat gerrymandering, drag dark money into the daylight, protect the franchise, crack down on big-money super PACs.

The bill passed easily out of the House. But it died on arrival in the Senate. Not only would no Republican support it; Sen. Manchin, a key moderate member of the Democratic caucus, announced his opposition to the bill, saying it was a partisan piece of legislation affecting an issue that required bipartisanship. “Congressional action on federal voting-rights legislation must be the result of both Democrats and Republicans coming together to find a pathway forward,” Manchin said at the time, “or we risk further dividing and destroying the republic we swore to protect and defend as elected officials.”

In the same statement, Manchin also declared his opposition to weakening the filibuster. Democrats quickly offered up a revised version of the bill, one that Manchin was generally more supportive of, but it died in the face of a Republican filibuster. And with that, it seemed, the For the People Act was well and truly dead.

Manchin in the Middle

But the small group of Democratic lawmakers and the dozens of activist groups pushing for the bill took hope from another statement of Manchin’s. In a tweet in May about the need to reauthorize the landmark Voting Rights Act, Manchin said that “inaction is not an option.” The rest of the tweet talked about the need to act in a bipartisan way to reauthorize the VRA, but it was those initial five words — “Inaction is not an option” — that Senate Democrats and their allies seized upon. Speaking on the Senate floor last month, Sen. Schumer said: “As Senator Manchin said earlier this year regarding congressional action on voting rights, inaction is not an option. I agree with Senator Manchin in that regard.”

After the defeat of the For the People Act in June, Manchin released a list of requests for what he wanted to see in a retooled voting-rights bill. Democrats spent the rest of the summer incorporating Manchin’s demands into a new compromise bill called the Freedom to Vote Act. The new bill, which was announced in late September, contains much of what was found in the For the People Act — provisions to increase disclosure of dark money, make Election Day a federal holiday, enact automatic voter registration at DMV offices, and pass nationalized standards for expanded access to early and same-day voting. While the bill pares back reforms to the Federal Election Commission, redistricting reform, and the use of voter-ID policies, it includes a raft of new protections against efforts to subvert or sabotage the vote-counting and certification process along the lines of what happened after the 2020 election.

Despite the changes to parts of the bill, reformers say it would still make huge improvements to everything from voting and campaign funding to shoring up American democracy against the next onslaught of “stop the steal” skullduggery. “Following the 2020 elections, in which more Americans voted than ever before, we have seen unprecedented attacks on our democracy,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-Minn.), a leader on voting rights in the Senate, tells Rolling Stone. “We must take action. The Freedom to Vote Act will protect the right to vote by setting basic national standards to ensure all Americans can cast their ballots in the way that works best for them, regardless of what ZIP code they live in.”

Democrats not only crafted the Freedom to Vote Act to address Manchin’s concerns, they also gave him several weeks this fall to try to find 10 Republican senators who would support the new bill. From June onward, Democrats have adopted a Manchin-centric strategy, according to multiple congressional aides who have worked behind the scenes on the bill.

Recent reporting indicates Manchin has not found GOP votes for the new bill, even though it contains policies that are popular with Democrats, Republicans, and independents, according to recent polling. “It’s lawmakers on the Republican side of the aisle in Washington standing against this reform; it’s not Republican voters,” says Rep. John Sarbanes (D-Md.).

Filibuster Reform — or Bust

Which brings us to Wednesday’s vote. The vote is not about whether to pass the Freedom to Vote Act — it’s a procedural vote on whether to begin debating the bill. If Republicans filibuster that vote, as they’re expected to do, then the final phase of Senate Democrats’ strategy begins.

To pass the Freedom to Vote Act, Democrats will need to change the filibuster. Beltway media outlets use scary language to describe this process — “going nuclear” or using the “nuclear option” is the typical formulation — but in truth, the Senate changes the rules of how it does business all the time. Between 1969 and 2014, the Senate made 161 such changes, according to research by the Brookings Institution. The Senate changed the filibuster during Barack Obama’s presidency to confirm lower-court judges by a simple 50-vote majority; it did so again during Donald Trump’s presidency to confirm Supreme Court justices and cabinet secretaries.

The bigger hurdles to filibuster reform are Manchin and Sinema. Manchin himself called for filibuster reform in 2011, but has since come out strongly against it, saying the existing rules of the Senate protect small, rural states like his. “We will not solve our nation’s problems in one Congress if we seek only partisan solutions. Instead of fixating on eliminating the filibuster or shortcutting the legislative process through budget reconciliation, it is time we do our jobs,” he wrote in April.

Sinema, for her part, takes the opposite position of her more liberal counterparts: She argues that a strong filibuster is good for the Senate and for democracy. “The filibuster compels moderation and helps protect the country from wild swings between opposing policy poles,” she wrote in a June op-ed. The filibuster, she rightly points out, has been used to stop policies that Democrats deem dangerous or hateful — indeed, Democrats used the filibuster hundreds of times during Donald Trump’s four years in office.

If anyone can convince Manchin and Sinema — and that’s a big if — it’s President Biden. Publicly, Biden has signaled his support for bringing back the talking filibuster, which would require physically holding the Senate floor and speaking continuously for however long you intended to block a vote. Privately, as Rolling Stone first reported, Biden has told Schumer he’s ready to pressure Manchin, Sinema, and other resistant Senate Democrats to vote in favor of filibuster reform of some kind.

This is the endgame, Democrats and activists say. It will play out over the next few weeks, this pressure campaign to get all 50 Senate Democrats to approve filibuster changes in order to pass the Freedom to Vote Act along party lines. If Democrats can’t find the votes to so much as tweak the filibuster, then their once-in-a-generation voting-rights bill is dead.

All year long, Democratic leaders have invoked Manchin’s line that “inaction is not an option.” Senate Democratic leader Schumer, likes to go one step further. “Failure,” he says, “is not an option.” That vow will now face its toughest test yet.

Former President Donald Trump. (photo: Getty)

Former President Donald Trump. (photo: Getty)

The investigation by Westchester District Attorney Miriam E. "Mimi" Rocah is examining property valuations at Trump National Golf Club Westchester, north of New York City. A source with knowledge of the investigation has confirmed that the town that collects local taxes from the course, Ossining, has received a subpoena from Rocah's office for documents.

The investigation was first reported by The New York Times. The Times also reports that Rocah has subpoenaed records from the golf club.

Rocah's office declined to comment on the case.

Trump and the town of Ossining have tussled for years over property tax assessments.

In a 2018 interview with WNYC and ProPublica, Town Supervisor Dana Levenberg noted that Trump once claimed a value for tax purposes that was less than a tenth of what the town believed the property was worth. After Trump was sworn in, his business continued its pattern of suing Ossining over its property tax assessments.

In that interview, Levenberg pointed to the awkwardness of facing a lawsuit from the business of a sitting U.S. president. "It is certainly uncomfortable at best," she said.

Levenberg did not comment on the district attorney's probe.

A Trump organization spokeswoman, Kimberly Benza, responded over email: "The suggestion that anything was inappropriate is completely false and incredibly irresponsible." She noted that Trump and the town of Ossining agreed to a compromise on valuing the property last July.

That agreement reduced the property's assessed value and resulted in a refund for Trump of $875,000, according to the New York Times.

Rocah's probe adds to Trump's considerable legal headaches in New York. In July, Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr. brought an indictment against the Trump Organization and its longtime chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, over what Vance says was a 15-year scheme to avoid state, local and federal taxes through undeclared perks and other illegal maneuvers. The Trump Organization and Weisselberg have pleaded not guilty.

The New York Attorney General, Letitia James, is conducting her own civil probe of Trump Organization business practices.

Both Vance and James have signaled an interest in examining Trump's financial statements about another Westchester County property, the Seven Springs estate. But the Ossining golf club does not appear to have drawn their attention.

The Trump National Golf Club Westchester boasts a waterfall more than 100 feet high, tennis courts and a pool. Members of the club have included Jack Nicholson, Bill Clinton and Rudy Giuliani. Trump purchased the land for the club in a foreclosure sale in 1996, paying $8 million. Trump began contesting his property tax assessments as early as 2002.

Rahm Emanuel, President Biden's nominee to be ambassador to Japan, attends a hearing to examine his nomination before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Oct. 20. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

Rahm Emanuel, President Biden's nominee to be ambassador to Japan, attends a hearing to examine his nomination before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Oct. 20. (photo: Patrick Semansky/AP)

Emanuel, a consummate Democratic insider and former chief of staff to President Barack Obama, conceded that he could have done more to remedy the “distrust” among Chicago’s Black residents during his mayorship and said he remains troubled by the killing of 17-year-old Laquan McDonald.

“There’s not a day or a week that has gone by in the last seven years I haven’t thought about this,” he told members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

The confirmation hearing took place on the seven-year anniversary of the police shooting, which resulted in the firings of police officers and a federal probe. The delayed release of dashboard-camera video of the shooting after Emanuel won his second term for mayor — 13 months after the incident — led to accusations of a coverup.

But most Democrats on the panel, as well as some Republicans, suggested that the matter should not prevent Emanuel from obtaining the coveted diplomatic post.

“You can’t be a mayor, especially in a city like Chicago, without picking up some scar tissue on the way,” Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) said. “Your description of what you learned along the way . . . those lessons were challenging and painful for you during your entire tenure, but you served in an admirable way.”

In an early display of diplomatic dealmaking, Emanuel secured an introduction at the hearing from Sen. Bill Hagerty (R-Tenn.), who urged members of both parties to support the nomination. Emanuel also received positive remarks from several Democrats and the top Republican on the committee, Sen. James E. Risch (Idaho).

Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-Ore.) stuck out among lawmakers for peppering Emanuel with questions and expressing skepticism over his claims that the reason he didn’t move to release the dash-cam footage sooner was to avoid prejudicing the legal proceedings.

“The mother of Laquan McDonald learned about the nature of the shooting when she was called by the funeral house who said to her, ’Do you realize your son was shot multiple times, his body was riddled with bullets?’ She didn’t know . . . that information hadn’t been shared with her,” Merkley said.

“It seems hard to believe that all those things happened and yet you were never briefed on the details of the situation when you were leading the city,” he added.

Emanuel noted that his nomination came with the support of the leadership of the Chicago Black Caucus and the great uncle of McDonald.

“This is a tragedy that happened,” Emanuel said. “No city of any size has not confronted the gulf and the gap that exists between police practices and the oversight and accountability. I made efforts. . . . They missed the mark because they totally missed how deep that distrust is.”

The largely cordial atmosphere during the hearing stood in contrast to the opposition Emanuel’s nomination faced among progressive lawmakers in the House, such as Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.), who called the appointment “deeply shameful.”

A number of the panel’s most liberal members did not attend to question Emanuel, including Sens. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii), Cory Booker (D-N.J.), and Edward J. Markey (D-Mass.). It was unclear why.

Earlier in the day, the Senate panel also examined the nomination of Biden’s nominee for ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns.

The career diplomat and former ambassador to NATO also won bipartisan praise as he conveyed his preference for a tough policy on China.

Burns accused Beijing of “stonewalling” the international community about the origins of covid-19, saying it needs to be more transparent about the virus. “We need to push the Chinese to come clean about what happened,” he said.

Burns also said China’s “genocide in Xinjiang” and aggressive actions toward Taiwan must stop. China rejects the U.S. government’s view that its campaign of mass detention and sterilization of Uyghur Muslims amounts to genocide.

A woman waves a Black Lives Matter flag Tuesday outside the Glynn County Courthouse in Brunswick, Ga., where jury selection is underway in the murder trial of three men charged in the death of Ahmaud Arbery. (photo: Octavio Jones/Reuters)

A woman waves a Black Lives Matter flag Tuesday outside the Glynn County Courthouse in Brunswick, Ga., where jury selection is underway in the murder trial of three men charged in the death of Ahmaud Arbery. (photo: Octavio Jones/Reuters)

There were no remnants of Ahmaud Arbery’s blood on the streets of this coastal town after he was fatally shot on Feb. 23, 2020. No flowers or stuffed animals to memorialize the 25-year-old Black man who had been on a jog when prosecutors say two white men tracked him down and killed him.

Other than a man mowing his lawn, it was uneventful on the streets that are lined with modest homes and prodigious trees.

Nine miles away, inside the Glenn County Courthouse, though, jury selection had begun for the trial of the two men — Travis McMichael and his father, Gregory McMichael — and a neighbor, William Bryan, who videotaped the encounter on his cellphone. Lawyers for the three men say they were acting in self-defense; all three are charged with murder.

Outside the courthouse, a collection of religious and civic leaders — Black and white — met on the steps of the building in a show of unity.

It was as much a collective prayer for the survival of the town as it was an attempt to comfort Arbery’s family.

All eyes on the jury

While the courthouse rally Monday emphasized the community's coming together as the trial began, the possibility that the McMichaels and Bryan may be acquitted is leaving residents tense and anxious.

“Bottom line,” said Micah Rich, a Brunswick native who now lives in Savannah, “if these men are not found guilty, the jury is telling us that our lives don’t matter, that you can see a guy get killed on video, a guy who was doing nothing but jogging, and no one pays for it. If we have to go through the jury somehow justifying that, well, I’m not predicting an explosion. You can count on it.”

And therein lies the pressure on the 12 people who will make up the jury. It’s not just three defendants on trial, local leaders said.

“The criminal justice system is on trial — again,” said John Perry, a former president of the Brunswick NAACP who resigned to run for mayor. “Part of my message has been that we can passionately pursue justice without peace being the expense. ... But for the Black community, we’ve been appalled by what we saw on that video. So the trial will let us know as Black and brown people if we have a justice system that we can trust to be fair for all people.”

Of major concern for the Black community is the jury pool. Brunswick is predominantly Black, but the trial is taking place in Glynn County, where only 16 percent of the residents are Black, 4 percent Latino and 78 percent white. Jury selection for the trial is expected to last at least two weeks, as 600 people are were called for the process this week and potentially another 400 next week to find 12 jurors and four alternates.

“It is a lived experience for Black people in America that we can never take for granted that a white person will be convicted for killing a Black person,” attorney Benjamin Crump, who represents Arbery’s father, Marcus Arbery, said near the courthouse. “We are here focused on justice. A slap on the wrist would not be enough.”

Mario Williams, a civil rights lawyer from Atlanta, said the video, while decisive to many, may not be enough to sway a jury that he predicts will probably be composed of mostly white members.

“Even with video evidence, you’re doubtful,” Williams said. “And it also makes us have doubt because of where they are drawing that jury pool from. You’re in southern Georgia, which does not have a stellar history of dealing with prejudice and racism against Blacks. So, it’s scary because the thinking is, ’Can this jury pool do the right thing?’”

A complicated aftermath to a shocking shooting

How the case unfolded has not instilled confidence, either. Arbery was followed by the McMichaels and Bryan — because the father and son said they believed he had broken into homes in their neighborhood — cornered him on a street and Travis McMichael shot him with a shotgun. The McMichaels, who have been accused of being motivated by racial animus, have said they thought Arbery was a burglar. Bryan said he was just a witness.

No charges were brought until Bryan, who trailed the McMichaels in a separate car, released the cellphone video nearly three months later, and only after mounting public pressure and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation had seized the case from the Glynn County Police. Now, the McMichaels and Bryan face state charges of malice murder, felony murder, aggravated assault, false imprisonment and criminal attempt to commit a felony. Each has pleaded not guilty.

The district attorney at the time, Jackie Johnson, faces charges of obstructing prosecution of the McMichaels; the elder McMichael was a former police officer who had worked in the D.A.’s office as an investigator for more than 30 years before he retired in 2019. Several judges and prosecutors also recused themselves from the case. Superior Court Judge Timothy Wamsley from Savannah presides over the trial.

The defendants also face federal charges for hate crimes in a trial set for February 2022.

Arbery’s aunt, Diann Arbery Jackson, said she watched the video of her nephew’s death Monday morning before heading to court. “It does something to you,” she said, fighting back tears. “We just want justice.”

Some fear that a lack of what the Black people in town perceive as justice could result in civil disobedience.

“It’s not going to take much,” said Dwala Nobles, a Brunswick native who works with the local Episcopalian Archdiocese’s racial justice team. “When you have the visual evidence, then it’s very clear because your eyes are not lying to you. So, to have anything other than a guilty verdict means that those bodies sitting on that jury didn’t see what you saw. And the question would be: Why?

“That’s a level of denial that got us in this position in the first place in this country.”

Perry, the mayoral candidate, pointed to several changes that have followed Arbery’s death: The city hired its first Black police chief, Johnson was voted out as district attorney, and the Georgia Legislature repealed the state’s citizen arrest law and passed new hate crimes legislation.

“We’re still working together in the spirit of unity to make sure that race relations are what they need for us to be a healthy and thriving community,” Perry said.

Williams noted, however, that a harmonious community will be hard to achieve if there are no guilty verdicts.

“All hell’s going to break loose if they come out there with one of those typical, nonsensical verdicts,” he said. “There could be a lot of property damage and a lot of people that get hurt. And unfortunately, they’ll turn around and blame the people who are upset and rioting instead of blaming the people who actually are enforcing and ingraining racism throughout our judicial system.”

Bolivia President Luis Arce speaks during a morning briefing at the National Palace on March 24, 2021, in Mexico City, Mexico. (photo: hector Vivas/Getty)

Bolivia President Luis Arce speaks during a morning briefing at the National Palace on March 24, 2021, in Mexico City, Mexico. (photo: hector Vivas/Getty)

Citing a previous Intercept investigation, the Bolivian government said it has evidence of a plan to kill Luis Arce, a protégé of Evo Morales.

Bolivian authorities connected the plot to an effort, previously reported by The Intercept, by ex-Defense Minister Luis Fernando López to import U.S. mercenaries into Bolivia ahead of the election to block the left from returning to power after Morales had been ousted in a coup a year earlier.

Leading the advance team in Haiti that ultimately assassinated the president, according to Colombian authorities, was Colombian mercenary German Alejandro Rivera García, now held in Haitian custody.

According to the Minister of Government Carlos Del Castillo del Carpio, Rivera, who goes by “Colonel Mike,” entered Bolivia on October 16, 2020, under passport No. AV 969623, two days before the Bolivian election. He came into Bolivia from Colombia via the Viru Viru airport in Santa Cruz and stayed at the Hotel Presidente in La Paz, near the presidential palace.

The Intercept could not immediately independently verify the Bolivian government claims.

The Haitian president assassins were organized by the Doral, Florida-based security contractor Counter Terrorism Unit Federal Academy LLC, which is run by Antonio Enmanuel Intriago Valera and Arcángel Pretel Ortiz, who acted as a recruiter. Both Pretel and Intriago entered Bolivia between October 16 and 19, Bolivian officials said. Like Rivera, they entered via Viru Viru airport in Santa Cruz, the home base of the country’s right-wing opposition.

Two other men — Ronal Alexander Ramírez Salamanca, a former member of the Colombian Police, and Enrico Galindo Arias — entered through the Colombia-Viru Viru route, later staying with Rivera at the Hotel Presidente. As Del Castillo highlighted, the hotel is just blocks away from Plaza Murillo, where Arce’s presidential inauguration later took place.

At the press conference on Monday, Del Castillo said that the government had obtained and searched the emails of Joe Pereira, who The Intercept had identified as an organizer of a mercenary plot with López, the ex-defense minister, and that documents found in his possession confirmed the reporting. Del Castillo added that the newly uncovered documents laid out the specific goal of assassinating Arce.

The Intercept previously obtained audio of Pereira conspiring with López by phone. On the calls, López implicated ex-Interior Minister Arturo Murillo as supportive of the plan. Murillo has since been arrested in the United States and faces corruption-related charges.

According to Del Castillo, Pereira’s emails indicated that he sought to hire more than 300 mercenaries, including a former Blackwater contractor and a shooter who had trained with the U.S. military. (In the call shared with The Intercept, Pereira had promised López he could recruit “up to 10,000 men.”)

The Bolivian plot did not come to fruition. Arce dominated the field, making a runoff unnecessary by winning 55 percent of the vote and crushing the right-wing candidate by 40 points. The extent of the victory appears to have drained the energy of the renewed coup plotting.

Split Rock, with ladder. (photo: Kate Munning/Land Conservancy of New Jersey)

Split Rock, with ladder. (photo: Kate Munning/Land Conservancy of New Jersey)

Owl is a member of the Ramapough Lenape Nation, a community of a few thousand people who have lived in the Ramapo Mountains of New York and New Jersey for longer than anyone can remember. Among their white suburban neighbors, rumors about them have circulated for generations. As recently as 2012, a travel website called Weird NJ alluded to “stories of a degenerate race of people who live an isolated existence from the civilized world.” Outsiders have posited all sorts of theories about their origins, pegging them as the descendants of fugitive slaves or deserters from the Revolutionary War, but the Ramapough regard these tales as insidious lies. They say that they are among the last remaining members of the Ramapough Munsee band of the Lenape, the first inhabitants of the fields and forests that once stretched across what is now New York City and its suburbs. “This land has always been sacred to us,” Owl said.

On a recent Tuesday, Owl and a few dozen other tribe members and supporters gathered in a government building in Rockland County for a hearing that would potentially determine the fate of one of the most sacred parts of that land. If the county legislature were to vote in their favor that evening, the tribe would legally take possession of the Split Rock site, protecting it from the encroaching threat of real-estate development. The surrounding hills were too steep and rocky to have attracted much interest from developers in the past, which helps explain how the Ramapough, some of whom can see the New York City skyline from their front steps, have been able to hold on to their ancestral home for as long as they have. But in recent years, an influx of wealth into the area has driven more and more Ramapough out of their houses and off their land. Now there was a danger that they could lose access to Split Rock itself.

For the time being, the mountain property belonged to the Rockland County Sewer District, which operates a wastewater-treatment plant at the bottom of the hill. The District had decided to auction off the undeveloped 53-acre parcel in 2019, but developers had yet to snatch it up. The Land Conservancy of New Jersey, along with the Ramapough tribe and other partners, had swooped in and asked the District to halt the auction. After conducting an appraisal, the Land Conservancy offered to buy the property for $290,000. The environmentalist group had forged close ties with the Ramapough, and had made arrangements to turn the land over to the tribe if the deal went through. Both the tribe and the environmentalists envisioned an unbroken expanse of woodland eventually stretching from the southern tip of New Jersey all the way up to New York’s Bear Mountain, and thought of the Split Rock land as an important piece of that puzzle. It was now up to the Rockland County Legislature to decide whether to allow the sale to go forward.

At the hearing, Chief Dwaine Perry, the senior leader of the tribe, stepped up to the podium in a gray blazer and a traditional Ramapough Munsee roach, a headdress made primarily from the hair of a deer tail. A Vietnam veteran, he noted that the Lenape had allowed George Washington to use the Ramapo Pass during the Revolutionary War, giving the Continental Army a key strategic advantage over the British. Like all important tribal decisions, this one was likely made at the Split Rock site, he said. Later, I asked if he had spent much time there as a kid. “The only thing I really knew about Split Rock was that the women, the elders, would go up there and do ’something Indian,’” he said. “At the time, what that meant was, ’You do not ask.’” He now understood why they had been so careful to keep their ceremonies a secret. In the 1960s, white supremacists burned crosses on the mountain, a deliberate act of desecration, he figured. Less has changed since that time than one might hope. Last year, someone spray-painted an American flag on one of the boulders.

The next speaker was David Johnson, an independent archeologist who said he had studied hundreds of Native American ceremonial sites. Split Rock was “one of the most important” of all of them, he said. A lifelong resident of Poughkeepsie, Johnson spent years investigating the Nazca Lines, a network of ancient geoglyphs in the desert of southern Peru. “Then I came back to New York State and realized I had this in my backyard,” he told me. According to Johnson, Split Rock sat at the center of a complex of similar sites — boulders that had been moved by glaciers and modified, in various ways, by human hands. If you knew how to interpret these formations, you could travel across the region from one site to another as though following a “Rand McNally map of the Native Americans.” The Lenape viewed each of these sites as a portal between the present world, the underground realm of ancestors, and the spiritual world of the sky above, Johnson said. At least once a year, Split Rock’s connection to the celestial world would have been especially clear. On the morning of the winter solstice, according to Owl and other witnesses, sunlight shoots through the shaft in the rock, projecting a laserlike beam onto a nearby boulder.

The possibility of developers claiming the property represented just the latest threat to the Ramapough land and people. As a 2007 report by the state of New Jersey had noted, the Ramapough faced “blatant discrimination” and “significant and direct threats to their physical and economic well-being.” In just the last few years, an oil company had attempted to thread a pair of pipelines through the mountains; a private homeowners association called the Ramapo Hunt … Polo Club had been trying to shut down the tribe’s prayer camp; and the Environmental Protection Agency had announced what the tribe considered a dangerously inadequate plan to clean up the toxic sludge that the Ford Motor Company had dumped on their land back in the ’60s and ’70s. “It is a great stain on the history of the United States what has been done to Native Americans in this country,” Itamar Yeger, a county legislator, said at the hearing. The proposed measure was “one small step that we can take” to “right the wrongs,” he added. The measure was put to a vote, and the legislators, all of them, let out a chorus of ayes.

Afterward, as tribe members mingled outside, some expressed amazement that the hearing had gone so well. Stewart and Joyce DeGroat, cousins, reflected on the long history of real-estate scams that had cheated the Lenape out of nearly all of their land. According to the well-known apocryphal legend, the Lenape sold the island of Manhattan for some trinkets and beads in 1626. “We make some of the best jewelry in the world,” Stewart said, holding out a beaded necklace that Joyce had made for him. “Why would we need beads from you?” Joyce told me that she hoped that the perception of the Ramapough was finally changing. “I know a lot of people look at us like we’re in a cult,” she said. “We’re not a cult, all right? We know who we are.”

Owl regarded the hearing as a hopeful sign for the planet as a whole. “All Indigenous ceremonies are about respecting the environment, and that’s part of what’s important about this decision,” he said. “If we listen to Indigenous people and honor our ancestors, perhaps we can live in a better way than we’re living now.” Back when I visited the site with him, he had guided me through a brief meditation, and then had led me to the edge of an escarpment. In the distance, beyond the gray ribbon of the Hudson, rose the hazy outline of Manhattan. I asked Owl if everything that we were looking at had once been Lenape land. “It still is,” he said.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment