Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

But George W. Bush’s “Brooks Brothers Mob” took it to another level exactly 37 years later.

And the MAGA Monster’s attack on January 6, 2021, is far from over.

Like the 1865 murder of Abraham Lincoln, the elimination of JFK moved America toward the fascist totalitarianism we face today.

Debate still rages over who actually killed President Kennedy…and whether he would have pulled us out of Vietnam. But there’s no doubt that murder—combined with those of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy—-tore devastating holes in the fiber of American democracy. The movements for racial equality, social justice and an end to empire have yet to fully recover from those fascist hits.

On the 37th anniversary of the Kennedy assassination, an outright fascist coup followed in lock step. With the 2000 Florida vote count in deep dispute, a violent “Brooks Brothers Mob” physically terrorized Miami-area poll workers recounting the ballots in the very tight race between Vice President Al Gore and Texas Governor George W. Bush.

Dressed like Yuppies, these Hitlerian Brown Shirts were partly coordinated by Roger Stone, a vicious Nixon/Bush/Trump Dirty Trickster still assaulting American democracy. Future Supreme Court operatives John Roberts, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Barrett all played tangible roles in the Florida2000 attack.

That fascist mob prevented a credible count of the Florida contest. Bush lost the natonal balloting by 500,000 votes, but allegedly won Florida by 537. A later full recount showed Gore was the legitimate winner in Florida, which would have given him the Electoral College.

But in the wake of the 11/22/2000 murder of the electoral process, the Supreme Court’s

absurd Bush v. Gore decision gave W the White House. The horrendous Bush2 nightmares of 9/11, the Iraq/Afghan Wars, another stolen election in Ohio 2004, the Katrina drowning of New Orleans, the 2007-9 Big Short crash followed in a cavalcade of catastrophe.

On January 6, 2021, Trump—-aided by Roger Stone, among many others—-followed suit with his assault on the Capitol. The intent was forever the same—-to destroy American democracy and sub in a dictatorship.

Trump lost the 2020 election by more than 7,000,000 votes, the highest margin of defeat for all but two American incumbents (Herbert Hoover in 1932, Jimmy Carter in 1980).

But like any fascist autocrat, Trump had long since announced he would accept no electoral outcome that did not assure his forever presidency. What many Americans have yet to grasp is how dead serious he was about doing it….how close he came…and how obsessed and those around him are about still winning.

As Congressional hearings are now showing in devastating detail, January 6 was no random attack. Trump, Stone, Steve Bannon, attorney John Eastman, Rudy Giuliani and others in that fascist inner cabal had detailed plans for overturning the 2020 election and making Trump America’s own Iron Heel. The blueprint was intricate, detailed….and came within perhaps an hour of succeeding.

As we are seeing in ever-more horrifying detail, the Trump Junta had worked out the numbers on how exactly how many state delegations to the Electoral College they needed to subvert to win. They projected how blackmailing or killing Mike Pence could give them the White House essentially forever. How police protection at the Capital could be sabotaged. How their well-funded, militarily-coordinated mob could do in 2020 what their better-dressed predecessors had done in Florida 2000.

The plot temporarily failed for many reasons—-but not for lack of intent. Ever incompetent, January 6 was just another of Trump’s innumerable bankruptcies.

But he is still very much in business. And his road to dictatorship is painfully clear.

The viral holes in American democracy are many and deadly: money dominating politics, corrupted legislatures, the Electoral College, gerrymandering, disenfranchisement of the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico, the debilitating Drug War, stripped voter rolls, corrupt secretaries of state and local election officials, voter suppression, class/race/generation-based electoral terrorism, rigged vote counts, fake recounts, pre-determined audits and more.

As Trump has made clear, if there are fair and reliable elections in America, no Republican would ever win another office.

The Election Protection/Voter Enhancement movement that erupted from stolen Florida 2000 and Ohio 2004 has moved mountains. Despite the usual comatose response from the corporate wing of the Democratic Party, it has laid the groundwork for an electoral process that can actually work.

In 2020, the Pandemic’s demands for universal paper balloting by mail, with digital scanning and reliable vote counts, made all the difference. Among much more, the EP movement’s work for the Georgia Miracle and against the fake “Ninja” Arizona “recount” has been emblematic and essential.

But it was very very close. Had hackable electronic voting machines dominated in 2020 instead of the paper balloting demanded by the Covid and coordinated by the Election Protection movement, Trump would now be rounding up dissidents (probably including you) and sending us all to Guantanamo and the rest of the American prison gulag, for indefinite detention and likely execution.

That remains the Trump-Stone-Bannon dream, and they’re committed to making it come true in 2022 and 2024.

The game plan is simple: raise as much money as needed to buy the upcoming elections. Retain the Supreme Court as the ultimate election thief, as in Bush v Gore and so many other anti-democracy rulings before and since. Protect the Electoral College. Deny DC and Puerto Rico statehood. Deepen gerrymandering. Capture Confederate/Heartland state legislatures and use them to pass repressive registration laws, rig the balloting and flip the Electoral College. Take the secretary of state offices and local election boards throughout the US to corrupt the electoral process on the ground. Terrorize voters and vote counters. Fake recounts and audits where there are losses. Repeat the 2000 Brooks Brothers assault where necessary. Assassinate whoever gets in their way, as per Evers/X/King/the Kennedys.

The Trump-Stone-Bannon cabal has made it absolutely clear they seek a fascist dictatorship, and will do all the above and more to get it.

We have no excuses. We know what is coming. We know how to organize to defeat it.

What are you gonna do about it?

Harvey Wasserman co-convenes the Grassroots Emergency Election Protection Zoom Mondays, 5pm ET via www.electionprotection2024.org. His People’s Spiral of US History will be published in January, 2022 at www.solartopia.org.

Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

Tony and Cherie Blair bought a £6.5 million office in Marylebone by acquiring a British Virgin Islands offshore company. (photo: WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Tony and Cherie Blair bought a £6.5 million office in Marylebone by acquiring a British Virgin Islands offshore company. (photo: WPA Pool/Getty Images)

Crushing the tax haven racket is a big political challenge, but the steps needed are straightforward and simple.

The investigation should be particularly enraging for ordinary citizens everywhere because it found 35 current and former world leaders who are making use of complex financial maneuvering to conceal their wealth, avoid taxes, or both.

At the same time, readers may feel some despair: The malfeasance that the ICIJ’s reporting reveals appears so byzantine that stopping it seems beyond the capacity of democratic governance. In 2004, President George W. Bush encouraged Americans to embrace this sense of futility, saying there was no point in raising taxes on the wealthy because “real rich people figure out how to dodge taxes.”

In reality, though, there is no technical reason the world of international financial secrecy and all its associated injustices could not be eliminated. The challenge is purely a political one. This doesn’t mean it’s not daunting, especially since the Pandora Papers show that the people who write the laws often are doing so not just on behalf of their wealthy patrons but also for themselves. But it does mean that no one should fall for specious claims that it’s impossible.

This is especially important now as societies worldwide split ever more grievously in two. It’s bad enough that tax havens shift the tax burden from the superrich onto everyone else. The greatest damage they cause, however, is feeding the accurate, corrosive understanding across societies that there is one set of rules for regular people and a completely different one for those ensconced at the top of the pyramid.

For example, one especially infuriating discovery in the Pandora Papers is that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair and his wife avoided over $400,000 in taxes by buying an offshore firm that owned a London townhouse worth almost $9 million. Blair was by far the most significant prime minster of the past 40 years from the Labour Party, the counterpart to the Democrats in the U.S. There simply can’t be functional liberal politics, which asks everyone to contribute to the common good, led by people like Blair, who actively evade doing so.

To understand what can be done about offshore tax havens, it’s important to understand who uses them, and why. First, they can serve as a means for tax avoidance, which is carried out on a large scale by corporations and is generally legal (partly because corporations help write the laws). Second, there’s tax evasion, which is mostly carried out by individuals and is illegal.

The Pandora Papers are generally not about corporate tax avoidance. Ending corporate tax avoidance would require changing our current “territorial” tax system, under which corporate profits are taxed in the countries where the companies claim they were earned, to a “formulary apportionment” system, under which taxes would be assessed on less easily gamed metrics, such as sales or payroll.

Rather, the Pandora Papers revelations are about the behavior of individuals. Tax havens allow individuals to hide assets thanks to two simple attributes: The havens often do not report the assets to the relevant tax authorities, and they have strict secrecy laws that can obscure who the ultimate owners of assets are.

Gabriel Zucman, an associate professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley, proposes several straightforward ways to address this. Zucman is one of world’s leading experts on tax havens and the author of the short, general audience book “The Hidden Wealth of Nations.”

Zucman points out that there has been progress on the first front already. The Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, passed by Congress in 2010, imposed the U.S.’s rules on financial institutions worldwide. Under FATCA, banks in the Bermudas, Switzerland, the Cayman Islands, and every other country must search their records for accounts held by U.S. citizens and then report their income to the IRS.

FATCA’s passage created momentum for similar measures in other countries. What is needed now, Zucman says, is for this momentum to continue and for other countries, individually or collectively, to join together to require foreign banks to transmit the income of each country’s citizens to that country’s tax authorities.

However, thanks to trusts and shell corporations, financial institutions can in many cases truthfully say that they don’t know who owns the assets they hold. This problem could be dealt with by an international financial registry of exactly which individuals own which assets.

Zucman believes such a registry is “in no way utopian.” Countries already have such registries for one kind of wealth: property. And while it’s little known, there are now private registries for many other kinds of property. The Depository Trust Company keeps track of the ownership of all stock issued by U.S. companies. Euroclear France does the same for French corporate stock. Euroclear Belgium and Clearstream do so for bonds issued by U.S. companies but denominated in European currencies.

The already existing databases could plausibly be merged into one. This would require the supervision of a public institution with extensive financial expertise. But we already have one of those: the International Monetary Fund.

This would not directly solve the problem of financial obfuscation — the IMF under this scenario would only have information pointing to ownership by trusts, anonymous corporations, and the like. Untangling the various layers of secrecy would be expensive, laborious, and sometimes impossible.

But Zucman has a sneaky solution: The IMF should collect a 3 percent wealth tax on all stocks, bonds, mutual funds, land, and property in such a registry that would be refunded if the ultimate owners unmasked themselves.

The individuals revealed in the Pandora Papers would thus have two options: They could keep their assets secret, and thereby be eaten away by the 3 percent tax every year to the point where there was no financial advantage to utilizing tax havens, or they could reveal themselves, making their assets taxable and therefore also making tax havens pointless.

Again, this is undoubtedly a large political mountain to climb. And those who oppose financial transparency will claim that there is no way to force tax haven countries to comply. But this is simply false: The U.S. and the European Union have enormous power that they constantly wield against other nations when they wish to. Zucman calculates that France, Italy, and Germany could compel even a rich country like Switzerland to agree to any needed transparency changes by placing a tariff of 30 percent on Swiss products. This would cost Switzerland more than it takes in as a tax haven. It would also be legal under World Trade Organization rules, because that level of tariff would allow the three countries to recover approximately the same amount in tax revenues that Switzerland is costing them.

Meanwhile, there are many international public interest organizations that understand the significance of the issue and are trying to push it onto the global agenda. “This is where our missing hospitals are,” a representative for Oxfam International said in a press release, in response to the publication of the Pandora Papers. “This is where the pay-packets sit of all the extra teachers and firefighters and public servants we need. Whenever a politician or business leader claims there is ‘no money’ to pay for climate damage and innovation, for more and better jobs, for a fair post-COVID recovery, for more overseas aid, they know where to look.”

Members of Congress have only been required to disclose their finances since 1978. Until 2010, Americans could hold assets overseas that would not be reported to the IRS. A provision banning shell companies in the U.S. was recently inserted into a National Defense Authorization Act that was passed over a veto by President Donald Trump just before he was extracted from office. Financial secrets have been dragged out into the light before, and they can be again.

Harvey Wasserman co-convenes the weekly Election Protection 2024 ZOOM. His People's Spiral of US History is at www.solartopia.org.

Reader Supported News is the Publication of Origin for this work. Permission to republish is freely granted with credit and a link back to Reader Supported News.

A protestor calling for the closure of the Guantanamo Bay Prison on January 11, 2016, in front of the White House. (photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

A protestor calling for the closure of the Guantanamo Bay Prison on January 11, 2016, in front of the White House. (photo: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images)

Can America’s legacy of torture be a “state secret” if it isn’t even a secret?

Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn (often referred to as “Abu Zubaydah”) is a Palestinian man who is currently held at the US prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. After he was captured in Pakistan in 2002, American officials concluded that Zubaydah was one of al-Qaeda’s top leaders, and he was repeatedly waterboarded, locked in a tiny coffin-sided box for hundreds of hours, denied sleep, and forced to remain in “stress positions,” among other abusive interrogation tactics — all in a vain effort to extract information that Zubaydah never possessed.

In 2006, the CIA formally concluded that it had made a mistake. Zubaydah, according to the agency, “was not a member of al Qaeda.” He has never been charged with a crime, but nevertheless remains a prisoner at Gitmo. According to his lawyers, Zubaydah cannot even testify in any legal proceeding regarding his torture, “because the Government summarily decided nearly twenty years ago that he would remain incommunicado for the rest of his life” — a decision that is confirmed by internal CIA communications from 2002.

None of the most important facts regarding Zubaydah’s detention and torture can reasonably be disputed. In 2014, the Senate Intelligence Committee released a lengthy report detailing the CIA’s use of torture. Although the full report is classified, Zubaydah’s name appears 1,343 times in an unclassified “executive summary” of that report and its accompanying documents.

Among other things, this summary reveals that Zubaydah “became ‘completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth’” during a waterboarding session.

There is overwhelming evidence that, for at least part of his ordeal, Zubaydah was held at a secret CIA facility in Poland. In 2015, the European Court of Human Rights determined that Zubaydah was held at such a facility in Poland from December 2002 until September 2003. Aleksander Kwaśniewski, the former Polish president who was in office during this period, admitted in 2012 that the Polish government “agreed to the intelligence cooperation with the Americans,” though he claimed that “we did not have knowledge of any torture.”

Yet the primary issue in Zubaydah is whether the United States can claim that Zubaydah’s torture and his detention at a CIA facility in Poland are “state secrets” that can be kept from Polish prosecutors investigating whether any Polish nationals were complicit.

In 2010, Zubaydah’s lawyers and several human rights groups filed a criminal complaint in Poland seeking an investigation into any Polish officials who contributed to Zubaydah’s detention and torture. Initially, this complaint proved fruitless, but after the European Court of Human Rights determined that “the treatment to which [he] was subjected by the CIA during his detention in Poland ... amount[ed] to torture,” Polish prosecutors reopened their investigation.

To aid this investigation, Zubaydah’s lawyers asked a US court to compel the testimony of two psychologists, James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen, who helped develop the torture techniques used on Zubaydah and other detainees — Mitchell and Jessen’s company was paid $81 million by the CIA to devise and oversee the agency’s use of torture. Zubaydah’s lawyers also seek documents from Mitchell and Jessen related to their client’s torture.

A federal appeals court held that at least some of the information sought by these attorneys should be made available to them. Although the Supreme Court has long held that the federal government may prevent private parties from obtaining information that, “in the interest of national security, should not be divulged,” the appeals court reasoned that the government cannot hide information that is already public.

“In order to be a ‘state secret,’ a fact must first be a ‘secret,’” Judge Richard Paez wrote in a fairly nuanced opinion laying out the process a trial court should use in determining what information about Zubaydah’s detention and torture may be disclosed to his lawyers — and, ultimately, to Polish investigators.

The federal government, meanwhile, has taken the firm position that nothing may be disclosed. Even if many of the facts about Zubaydah’s torture are widely known, the government argues in its brief, “first-hand evidence from Mitchell and Jessen would confirm or deny the accuracy of existing public speculation and risk significant harm to the national security.”

The government is so committed to its position that many publicly available facts cannot be confirmed that its brief even suggests that some of the information confirming that Zubaydah was tortured, and that he was detained in Poland, may be some kind of elaborate false flag. “Intelligence officers routinely deploy tradecraft to cloak the true nature of their activities and misdirect attention,” the brief explains. And thus, it claims that “public information” about Zubaydah “can be of uncertain reliability.”

So the Supreme Court must dive into the rabbit hole that is the Zubaydah case, with the United States unwilling to admit many facts that it cannot reasonably deny.

The “state secrets” doctrine, briefly explained

Some information presents such a genuine threat to national security that it should not be disclosed, even if a litigant would otherwise have a valid claim to it. Imagine, for example, that a party to a lawsuit wanted to know about troop movements in the middle of a war, or if they wanted to see documents that would reveal US diplomats’ bottom line in an ongoing negotiation with a foreign nation.

The seminal case involving federal claims that certain information is a state secret is United States v. Reynolds (1953). Reynolds involved a lawsuit brought by three widows whose husbands died while they were aboard a test flight of an Air Force bomber that contained secret electronic equipment.

The widows sought the Air Force’s official report on the accident, but the Air Force refused, claiming that it could not be disclosed “without seriously hampering national security, flying safety and the development of highly technical and secret military equipment.”

In agreeing that the government could withhold this report, the Supreme Court announced several principles that guide state secrets cases. Among other things, the Court explained that information should remain a secret when “there is a reasonable danger that compulsion of the evidence will expose military matters which, in the interest of national security, should not be divulged.”

At the same time, the Supreme Court required the government to clear certain procedural hurdles in order to prevent it from invoking this state secrets privilege too often. Among other things, the government may not claim this privilege unless there is a “formal claim of privilege, lodged by the head of the department which has control over the matter.” This senior government official must also engage in “actual personal consideration” of whether the privilege should be invoked — they cannot delegate this task to a subordinate.

The Court noted that the privilege is strongest when a party could obtain the information they seek through other means, and weakest when the opposite is true. “Where there is a strong showing of necessity,” according to Reynolds, “the claim of privilege should not be lightly accepted.” Nevertheless, the Court added that “even the most compelling necessity cannot overcome the claim of privilege if the court is ultimately satisfied that military secrets are at stake.”

Though the Supreme Court did not make this point explicitly in Reynolds, the judiciary is often in a position of weakness when the government claims that certain information must remain a state secret. The trial judge in Reynolds, for example, ordered the government to turn over the contested Air Force report so that the judge could review it in private to determine if it contained material that should be withheld. But the government refused to do so.

Ultimately, if the federal government simply insists that it will not turn over certain information no matter what, there’s not much that the courts can do.

The final chapter of the Reynolds case, moreover, offers a cautionary tale about what can happen if the courts are too quick to trust the government in state secrets cases. When the accident report at the heart of the case was declassified in the 1990s, the public learned that it did not even mention the equipment that the Air Force wanted to keep secret.

According to a Senate Judiciary Committee report, however, it did “contain embarrassing information revealing Government negligence (that the plane lacked standard safeguards to prevent the engine from overheating).”

What does all of this mean for Zubaydah?

The factors laid out in Reynolds offer fodder to both parties in the Zubaydah case. On the one hand, it’s hard to argue that at least some of the information sought by Zubaydah would “expose military matters which, in the interest of national security, should not be divulged,” when that information is already widely known and was already disclosed in the unclassified summary of a Senate Intelligence Committee report.

At the same time, it’s unclear that Zubaydah can make a “strong showing of necessity.” Why does he need Mitchell and Jessen to reveal information that is already in the public record?

Judge Paez’s opinion for the appeals court drew a line between information that is already known and information that remains secret. Some of the information sought by Zubaydah, Paez’s court ruled, such as “the identities of foreign nationals who work with the CIA,” should not be disclosed because doing so “risks damaging the intelligence relationship [between the United States and Poland] and compromising current and future counterterrorism operations.”

At the same time, already-public information such as “the fact that the CIA operated a detention facility in Poland in the early 2000s; information about the use of interrogation techniques and conditions of confinement in that detention facility; and details of Abu Zubaydah’s treatment there” could potentially be disclosed — although, even under Paez’s opinion, it’s not clear if Zubaydah is entitled to any of the information he seeks.

If a trial judge determines that there is no way to reveal the less sensitive information sought by Zubaydah without also disclosing genuine state secrets, then, under Paez’s approach, all of the information should be suppressed.

At this point, you may be wondering what all this means. Frankly, it is unclear what’s actually at stake in this case, at least for Zubaydah, if the only information he’ll be able to obtain is stuff that is already available to the public.

But even if Zubaydah has little chance of walking away with much new information about who is responsible for his torture, the case could have profound implications for future cases where the government wishes to keep certain information secret.

The federal government seeks an extraordinary level of judicial docility whenever it raises a state secrets claim. Its brief is gravid with phrases like “utmost deference,” and suggests that only executive branch “officials possess ‘the necessary expertise’ to make the required ‘[p]redictive judgment’ about risks to the national security.”

These are not frivolous arguments. The Court has historically warned judges against intruding too far into questions of foreign policy or national security — although the Court’s current 6-3 conservative majority has not always heeded these warnings since Democratic President Joe Biden took office.

But, as the Court emphasized in Reynolds, “a complete abandonment of judicial control would lead to intolerable abuses.” Imagine a world where the government can commit any atrocity, then keep the truth of that atrocity secret forever.

This is why state secrets cases are hard. They require judges, often acting on imperfect information, to make difficult choices about when the interests of justice overcome fears about national security.

But Zubaydah also isn’t a typical state secrets case. It’s a case about whether the government will reveal horrible truths that are already largely known.

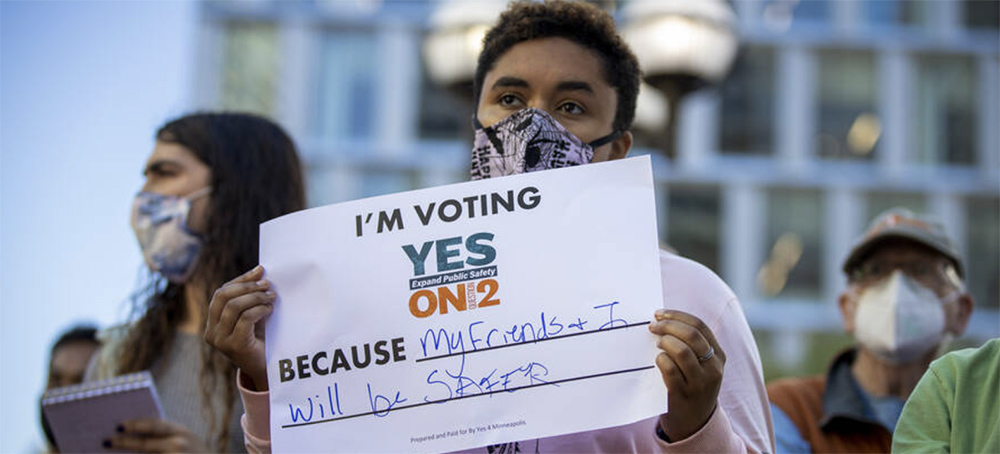

Olivia Wreford joins the September 17 rally organized by Yes 4 Minneapolis in support of a ballot measure to overhaul the city's police, up for a vote in November after a lawsuit briefly knocked it off the ballot. (photo: Henry Pan/In These Times)

Olivia Wreford joins the September 17 rally organized by Yes 4 Minneapolis in support of a ballot measure to overhaul the city's police, up for a vote in November after a lawsuit briefly knocked it off the ballot. (photo: Henry Pan/In These Times)

Will the city at the center of last summer’s racial justice protests decide to remake public safety? We’ll soon find out.

Yes 4 Minneapolis is working to amend the Minneapolis City Charter by removing a mandate for a mayor-controlled police department with a certain number of officers per resident (0.0017, to be exact). In its place, the amendment establishes a Department of Public Safety under the joint control of the mayor and the 13-member Minneapolis City Council.

The radical restructuring would allow for future revisions. The new department could be led by a civilian and could easily redirect funds from armed officers to alternative responders, such as social workers. It would also be subject to more democratic control: the City Council represents a more diverse constituency than the mayor, who is primarily elected by wealthier, whiter parts of the city.

For the better part of a year, the campaign has been scrambling to respond to a slew of cheap shots from the opposition, a loose coalition of liberal politicians, the police chief and nonprofit and business leaders. The most recent curveball was a last-minute lawsuit that alleged the amendment question, which will be on the ballot in November, should be thrown out because of so-called misleading language.

On September 14, a district judge ruled to disallow the ballot question. On September 15, Yes 4 Minneapolis converted a planned get-out-the-vote rally to a demand-the-vote rally, where they would take the fight “to the streets,” Yes 4 Minneapolis communications director JaNaé Bates said. On September 16, the Minnesota Supreme Court overturned the earlier ruling. By September 17, the rally was back to its original purpose and had lost the momentum that could have carried people “to the streets.”

A shifting purpose wasn’t the rally’s only problem. The event was held at People’s Plaza to take advantage of the stately, copper-roofed Minneapolis City Hall as the backdrop. Periodically, however, trains blasted past, which would have drowned out the speakers had they not already been drowned out by the plaza’s fountains. According to Bates, the police had nixed the generator needed to power a sound system. Instead, speakers used a cheap microphone that barely carried sound unless it was held against their lips.

The rally felt like a distillation of the campaign’s general problems — complication after complication, wrapped up with much confusion. The opposition, meanwhile, has kept the campaign off-balance. One poll shows 49% support for the amendment to 41% opposed it. A month before the election, doorknockers suggest the split is even tighter.

Dirty tricks

The Black Lives Matter movement began as a social media hashtag in 2013 in the wake of George Zimmerman’s acquittal in the extra-judicial killing of Trayvon Martin. Committed activists grew the campaign into a nationwide Movement for Black Lives network grounded in an argument for police abolition.

Policing in the United States, abolitionists argue, is built on the institution of slavery and the genocide of Native Americans. These atrocities are the foundation of policing. Its architecture is heavily influenced by Jim Crow.

Meanwhile, the scope of policing continues to expand. For example, in the past four decades, police budgets have ballooned while mental healthcare budgets have shrunk — and police have had to absorb the mission of mental health practitioners. Police abolitionists argue that policing cannot competently do everything demanded of it and cannot be reformed away from its core mission of using racialized violence to protect “the interests of the wealthy,” as one Minneapolis abolitionist organization, MPD150, writes.

Instead, the Movement for Black Lives calls for reimagining public safety, with mental health experts, school counselors, trauma-informed interventionists and restorative justice programs taking the place of the police, as well as funds for education, jobs, clean air, a universal basic income and other supports for communities historically stripped of resources.

In the Twin Cities, Black Visions Collective has been doing that long-term abolitionist work. The group shut down a key transit line in 2018 during Super Bowl LII in a protest for Black lives, and in 2019, with allied group Reclaim the Block, got $242,000 shifted out of the $193 million police budget to fund the Office of Violence Prevention.

Then, on May 25, 2020, Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd. The city became the epicenter of a fiery global protest movement, which also became (by some counts) the largest in U.S. history.

“We never thought 2020 would happen the way it did,” says Kandace Montgomery, Black Visions co-executive director. “Changing the [city] charter was something that we had predicted for a few years down the road, like 2023. But the opportunity presented itself.”

Black Visions and Reclaim the Block moved quickly to pressure the city council for action. Two weeks after Floyd’s murder, a veto-proof majority of nine councilmembers publicly pledged to defund and dismantle the police department. Minneapolis seemed poised to become a test case of abolition.

By December 2020, the council had been all but thwarted.

An initiative by the council to dismantle the police department was blocked from the November 2020 ballot by the Charter Commission, a judicially appointed board. The council pivoted to cut the department’s budget — but a group of Minneapolis residents swarmed the budget hearings in opposition in late 2020. Two councilmembers who had pledged to defund then voted to maintain the police staffing level, effectively thwarting the budget cut.

Later, it would be revealed that the leader of the “grassroots” pro-police effort, Bill Rodriguez, was actually a public relations consultant from the suburbs who had lied repeatedly about living in Minneapolis. Rodriguez was supported by an economic development consultant named Eric Won, who holds a mayoral appointment on a city budget advisory committee. Together, according to emails obtained from the city, the two men offered to use Won’s influence to support business development in Councilmember Alondra Cano’s ward shortly before she voted to keep police staffing at its current level.

The same tranche of emails shows Won and Rodriguez also coordinated with Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, Police Chief Medaria Arradondo and a group of well-connected business and conservative community leaders, politicos and nonprofits.

This work grew into the coalition opposing the amendment change, composed of several interest groups.

The business and corporate interests were primarily represented by the Minneapolis Downtown Council, which sees the police department as necessary to keep downtown profitable. Real estate developers represent another significant part of the coalition, joined by the North Central States Regional Council of Carpenters.

Don and Sondra Samuels, leaders of anti-poverty nonprofits and two of the three plaintiffs in the lawsuit that temporarily threw out the ballot question, are the most visible of the centrist-leaning community and faith leaders. Members of this faction, mostly from North Minneapolis (a historically Black part of the city, due to a legacy of redlining), have been working for decades to incrementally reform the police department; they fear a sweeping reorganization of public safety could undo their efforts. They have a close relationship with Arradondo, a self-described “Northside baby” who also worked there as a beat officer.

The old guard of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party (the DFL is Minnesota’s Democratic Party, due to a fluke of history), mainly former city officials, represents another part of this coalition. They generally oppose comprehensive public safety reform in alignment with centrist Dems nationwide, including President Joe Biden, partly out of fear the GOP will use it as a wedge issue against them.

The last group, of course, is the police themselves. Arradondo has spoken out against the amendment, though the police union has remained quiet on the issue after becoming a flashpoint in the summer 2020 protests.

The mayor sits at the center. Frey signaled his broader political ambition in 2019 after a Twitter spat with former President Donald Trump. If re-elected in November, Frey will be mayor until 2025, leaving him free to run for governor or Congress in 2026. He may see this moment as an opportunity to build a constituency for a state or national run.

Of course, the factions are not clear-cut. Don Samuels is a former DFL city councilmember, and about half of the board of directors of Sondra Samuels’ nonprofit are corporate executives, consultants or lawyers.

“We did not go into this fight delusional,” says Yes 4 Minneapolis’s Bates. “[We knew] we were coming up against the Police Federation, big corporate lobbyists and corporate developers, as well as the current mayoral apparatus. They have been leveraging every bit of money and power against us.”

In short, Minneapolis has become a microcosm of the national opposition to the defund and abolish movement, with conservatives, wealthy interests and center-liberals driven by concern for neighbors, fear for property and an eye to their own political fortunes.

A slow start

The summer 2020 protest movement kindled a general openness to the question of defunding police (and the question of what investments can truly reduce crime), with some polls showing 41% support for shifting money from police departments into violence prevention initiatives. But as protests waned, the status quo reasserted itself. Trump and other Republican leaders used the movement to stoke fear, police unions threatened doom, Democratic mayors balked at budget cuts and the Democratic National Committee ran from “defund.”

In Minneapolis, after the Charter Commission blocked the first amendment attempt, activists decided to get the question on the ballot themselves. “[We] felt really clear that we needed to build a really robust coalition and a full campaign to get this thing on the ballot,” says Black Visions’ Kandace Montgomery. “And then get 50% plus 1 of the people in Minneapolis to vote for it.”

The plan sounded simple enough. What the amendment should actually say was more complicated.

Black Visions and Reclaim the Block sit on the radical end of a vibrant ecosystem of left-wing activism in the Twin Cities. Organizations range from TakeAction Minnesota, an advocacy group aligned with progressive Dems, to such openly socialist organizations as the base-building renters’ rights group Inquilinxs Unidxs por Justicia (United Renters for Justice). (Full disclosure: My wife, Jennifer Arnold, is executive director of Inquilinxs Unidxs, a member of Yes 4 Minneapolis.)

Black Visions had a strong roster of potential allies willing to talk police overhaul, but between fall 2020 and summer 2021, its coalition was slowed by a need to get “in alignment,” says Bates. The key divide was over the long-term vision of public safety: abolition or reform.

Montgomery argues for the abolition of policing — an institution grounded in racism — in favor of a completely different model of community investment. “When communities are well-resourced, they’re at their safest,” she says.

More reform-minded coalition members believe instead that police are necessary, but the notoriously violent Minneapolis Police Department needs to be replaced with something new.

The well-funded opposition, meanwhile, has built its campaign on spreading confusion about the amendment itself. For months, it has insisted the amendment would get rid of the police or the police chief. And Bates says those tactics worked.

“The lies and different disinformation initially did what it was created to do — to throw us off of our square and create confusion,” Bates says.

Legal battles further muddied the waters. The opposition has brought three related lawsuits to date. The first was against the city to demand it hire more police officers (as mandated by the City Charter). The judge ruled in its favor.

The second lawsuit targeted the original ballot question language, and the judge ruled in its favor, too. During Rosh Hashanah, the judge gave councilmembers (several of whom are Jewish) mere hours to revise the wording, lest it get tossed off the ballot.

The third lawsuit is the one that temporarily knocked the amendment off the ballot.

Yes 4 Minneapolis brought its own suit, too, challenging the wording of an explanatory note that would have accompanied the ballot question. The judge ruled in its favor, saying the note read like a “warning label.”

“We were trying to get in alignment while also facing absurd lawsuits, while also trying to land ballot language,” Bates says. “Some of your usual campaign activities had to be delayed.”

Yes 4 Minneapolis collected 20,000 signatures for a petition in April to secure the ballot question, then focused on internal organizing through August. Thanks in part to that work, Bates says the coalition reached an understanding: Reformers and abolitionists agree the status quo isn’t working.

Meanwhile, the opposition continues to promote disinformation, falsely claiming in glossy mailers that the amendment would “eliminate” the widely popular police chief, Arradondo, for example. Some of the attempts have backfired, however, such as a mailer that implied Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison opposed the amendment. In response, Ellison publicly announced his support.

Coming from behind

Yes 4 Minneapolis has done doorknocks, phone banks and information sessions, but much of their staff time has been spent just making sure core supporters understand the amendment, Bates says. They are only now starting to focus on the general electorate.

As of July 27, Yes 4 Minneapolis had more than $475,000, according to the most recent campaign finance filings. But it had spent just $6,200 on Facebook ads, compared to the opposition’s $47,000, as of September 27. (Neither side had paid for Google ads.)

“We’ll be on a lot of different platforms to engage different constituencies” in the coming weeks, Corenia Smith, campaign director for Yes 4 Minneapolis, told In These Times in mid-September.

Despite the slow start, Yes 4 Minneapolis has some advantages, first and foremost being its coalition members, including Black Visions, TakeAction Minnesota (which has spearheaded dozens of campaigns since 2006, from school tax levies to opposing voter ID laws) and Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 26 (with more than 8,000 members). Many of the groups are electoral campaign veterans and base-building organizations that have also engaged voters on the issue for months. TakeAction has been doing phone banking since March and doorknocking since the end of July, according to Katie Blanchard, TakeAction movement-building director. Black Visions has been doing doorknocks since the end of July, according to Montgomery. “Every coalition partner has been doing something in the field,” she says.

Yes 4 Minneapolis is finding it can flip some “no” voters simply by explaining what the amendment actually does. “It’s been really nice when we have conversations on the doors and we can correct [misinformation],” Smith says. “People just saying, like, ‘Oh, I totally thought it was this [other thing].’ ”

That point of distinction actually leads to another, potentially huge, advantage. In its hubris, the opposition chose for its main slogan, “a both/ and approach” — as in, both reform and police — which is what the ballot question is actually about. So if Yes 4 Minneapolis can get its message out, the opposition has nowhere to pivot. Even Mayor Frey has announced his support for a Department of Public Safety, though he opposes using an amendment to create it.

In another recent development, Bates came on in July to co-lead the campaign with Smith. A former nurse, Smith had just a few months of organizing experience when she was hired in February — a deliberate move by the campaign to cut against “a history of not trusting community members, not trusting Black folks, not trusting women to lead and not supporting them,” Bates explains.

Bates adds five years of experience as communications director for Isaiah, a faith-based racial and economic justice group. The campaign is also bringing on veteran politico Javier Morillo, former president of SEIU Local 26, as a political advisor.

Light at the end of the tunnel

Twenty minutes into the rally on that cool day in September, things were already languishing. There were maybe 100 attendees, almost exclusively staff of member organizations, volunteers and press.

Bates took the final slot. She set aside the cheap microphone and held up a bullhorn, opening with a chant: “We are here. We won’t leave. We’ll have a city where we can breathe.”

She praised the rallygoers for their hard work. She recounted the campaign, blow by blow. She criticized what she called undemocratic attempts to prevent the vote. She encouraged people to do more volunteer work. And then she closed with another chant.

Her 10-minute speech was longer than it needed to be, but Bates understood the opportunity. Where other speakers addressed the press, perhaps hoping the journos would carry some nugget of narrative back to the electorate, Bates spoke to the people who had come.

The Yes 4 Minneapolis campaign has been off to a slow start for many reasons, and the final vote is anyone’s guess. A volunteer named Jesse Mortenson, who has done a dozen doorknocks and phone banks, thinks it’s going to be tight. “About a third of people are ready for change,” Mortenson says. “About a third feel that something is wrong, but aren’t sure this is the right thing to do.”

And the last third?

“Twenty percent of Minneapolis votes Republican, so that’s most of that number,” Mortenson says.

If Bates continues to take a more prominent role, if volunteers keep turning out, if experienced allies continue their support and if the opposition doesn’t find a new way to sink things — then the campaign might just scramble into a clear lead. That’s a lot of ifs, but the campaign is in a better position than it was at the beginning of summer.

Meanwhile, Minneapolis remains the closest city in the nation to reinventing public safety from the bottom up.

Activists gather to protest the execution of Ernest Lee Johnson at the Boone County Courthouse. Johnson's execution is set for Tuesday. (photo: Julia Eastham/Missourian)

Activists gather to protest the execution of Ernest Lee Johnson at the Boone County Courthouse. Johnson's execution is set for Tuesday. (photo: Julia Eastham/Missourian)

Pope Francis was among those speaking out on behalf of Ernest Johnson, who killed three in 1994

Ernest Johnson died from an injection of pentobarbital at Bonne Terre state prison. In his written last statement, Johnson said he was sorry “and have remorse for what I do”. He said he loved his family and friends and thanked those who prayed for him.

He was pronounced dead at 6.11 pm, nine minutes after the dose was administered. A Missouri corrections department spokesperson said four relatives representing all three victims were present. Johnson’s witnesses included relatives and his lawyer. No relatives spoke after the execution.

The corrections spokesperson, Karen Pojmann, said 59 protesters gathered on the edge of the prison grounds.

It was the first execution in Missouri since May 2020 and the seventh in the US this year. The state moved ahead with executing Johnson despite claims by his attorney that doing so would violate the US constitution’s 8th amendment, which prohibits executing intellectually disabled people.

Johnson had a history of scoring extremely low on IQ tests, dating back to childhood. His attorney, Jeremy Weis, said Johnson also was born with foetal alcohol syndrome and lost about one-fifth of his brain tissue when a benign tumour was removed in 2008.

A representative for Pope Francis was among those who urged the Republican governor, Mike Parson, to grant clemency, telling him in a letter that the pontiff “wishes to place before you the simple fact of Mr Johnson’s humanity and the sacredness of all human life”. Parson said on Monday he would not intervene.

It was not the first time a pope has sought to intervene in a Missouri execution. In 1999, during his visit to St Louis, Pope John Paul II persuaded the then Democratic governor, Mel Carnahan, to grant clemency to Darrell Mease, weeks before Mease was to be put to death for a triple killing. Carnahan, who died in 2000, was a Baptist, as is Parson.

In 2018, Pope Francis changed church teaching to say capital punishment can never be sanctioned because it constitutes an “attack” on human dignity. Catholic leaders have been outspoken opponents of the death penalty in many states.

Racial justice activists and two Missouri members of congress – the Democratic representatives Cori Bush of St Louis and Emanuel Cleaver of Kansas City – also called on Parson to show mercy to Johnson, who is black.

Johnson’s crime shook the central Missouri city of Columbia nearly 28 years ago. He was a frequent customer of a Casey’s general store and court records show that on 12 February 1994 he borrowed a .25-caliber pistol from his girlfriend’s 18-year-old son, with plans to rob the store for money to buy drugs.

In a 2004 videotaped interview with a psychologist shown in court, Johnson said he was under the influence of cocaine as he waited for the last customer to leave at closing time. Three workers were in the store: the manager, Mary Bratcher, 46, and employees Mabel Scruggs, 57, and Fred Jones, 58.

On the video, Johnson said he became angry when Bratcher, who claimed not to have a safe key, tried to flush it down the toilet. He shot the victims with the borrowed gun, then attacked them with a claw hammer. Bratcher was also stabbed in the hand with a screwdriver. Police found two victims in the store’s bathroom, and the third in a cooler.

“This was a hideous crime,” said Kevin Crane, the Boone County prosecutor at the time. “It was traumatic, and it was intense.”

Police officers searching a nearby field found a bloody screwdriver, gloves, jeans and a brown jacket, and questioned Johnson within hours of the killings. At Johnson’s girlfriend’s house, officers found a bag with $443, coin wrappers, partially burned cheques and tennis shoes matching bloody shoe prints from inside the store.

Johnson had previously asked that his execution be carried out by firing squad. His lawyers argued that Missouri’s lethal injection drug, pentobarbital, could trigger seizures due to the loss of the brain tissue when the tumour was removed. Missouri law does not authorise execution by firing squad.

Johnson was sentenced to death in his first trial and two other times. The second death sentence, in 2003, came after the US supreme court ruled that executing the mentally ill was unconstitutionally cruel. The Missouri supreme court scrapped that second death sentence, and Johnson was sentenced a third time in 2006.

Of the six previous US executions this year, three were in Texas and three involved federal prisoners.

The peak year for modern executions was 1999, when there were 98 across the US. That number has gradually declined and 17 people were executed last year– 10 involving federal prisoners, three in Texas and one each in Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama and Missouri, according to a database (pdf) compiled by the Death Penalty Information Center.

People wade through floodwaters in Chaiyaphum province, northeast of Bangkok, Thailand. (photo: Thanachote Thanawikran/AP)

People wade through floodwaters in Chaiyaphum province, northeast of Bangkok, Thailand. (photo: Thanachote Thanawikran/AP)

The WMO's data show that water-related hazards have increased in frequency over the past 20 years. Since 2000, flood-related disasters have risen by 134 percent compared with the two previous decades, while during the same period the number and duration of droughts also increased by 29 percent.

In its new report entitled "The State of Climate Services 2021: Water," the WMO says that 3.6 billion people globally had inadequate access to water at least one month per year in 2018, and by 2050 this number is expected to exceed five billion.

"The situation is worsening by the fact that only 0.5 percent of water on Earth is useable and available freshwater," the report says.

The WMO's data show that water-related hazards have increased in frequency over the past 20 years. Since 2000, flood-related disasters have risen by 134 percent compared with the two previous decades, while during the same period the number and duration of droughts also increased by 29 percent.

Most drought-related deaths occurred in Africa, indicating a need for stronger end-to-end warning systems for drought in that region. Most of the flood-related deaths and economic losses were recorded in Asia, while Africa was hit the most by drought-related deaths.

"Increasing temperatures are resulting in global and regional precipitation changes, leading to shifts in rainfall patterns and agricultural seasons, with a major impact on food security and human health and well-being," says WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

Last year saw a continuation of extreme water-related events, which displaced millions of people and killed hundreds across Asia, while in Africa more than two billion people still live in water-stressed countries and suffer lack of access to safe drinking water and sanitation, according to the WMO chief.

Underlining the important role of water resources management in reducing water-related disasters, the WMO recommends that countries, especially small island developing states and least developed countries, increase investment in integrated water resources management and in drought and flood early warning systems.

The WMO also urges countries to fill the capacity gap in collecting data for basic hydrological variables, which underpin climate services and early warning systems, and national level stakeholders to co-develop and operationalize climate services with information users to better support adaptation in the water sector.

A warning sign is posted for people to stay out of the water after a major oil spill off the coast of California came ashore in Huntington Beach, Calif., Oct. 4, 2021. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

A warning sign is posted for people to stay out of the water after a major oil spill off the coast of California came ashore in Huntington Beach, Calif., Oct. 4, 2021. (photo: Mike Blake/Reuters)

The companies in charge had a duty to prevent the spill, the plaintiffs say.

The federal lawsuit, filed Monday in the Central District of California Western Division, claimed the companies in charge of operating the rig and connected pipelines caused harm to people, wildlife and the local ecosystem by failing to prevent the spill from the platform about 4.5 miles from shore, known as "Elly."

The lawsuit also accuses the defendants of failing to warn or provide the public with "adequate and timely notice of the hazards and their impacts."

"At the time of this complaint's filing, deceased animals were washing up covered in oil on the shorelines of the Affected Area and a large ecological reserve nearby had suffered tremendous damage," the lawsuit stated, defining the "Affected Area" as the stretch of coast between Huntington Beach and Newport Beach and the defendants as Amplify Energy Corporation its subsidiary, the Beta Operating Company and other affiliates that may also hold responsibility.

A maximum of 144,000 gallons leaked into the Pacific Ocean after a pipe broke Saturday morning, according to officials. By early Sunday morning, the oil had reached the shore, fanning out over an area of about 5.8 nautical miles and entering the Talbert Marshlands and the Santa Ana River Trail, according to the city of Huntington Beach.

As a result, nearby beaches were closed to facilitate the cleanup and prevent residents from inhaling toxic fumes from the crude oil. Dana Point Harbor, about 30 miles south of Huntington Beach, became the latest location to close on Tuesday morning.

About 300 people are currently cleaning up the oil spill and an additional 1,500 people will be working on the effort by Wednesday, Gov. Gavin Newsom said Tuesday afternoon.

The main plaintiff in the lawsuit, Peter Moses Gutierrez, is a disc jockey who frequently performs on Huntington Beach, according to the lawsuit. Gutierrez expects to lose a "substantial amount" of business in the foreseeable future as a result of the spill, the complaint alleges.

Gutierrez and other plaintiffs claim they have also been exposed to toxins from the oil, according to the lawsuit.

The nearly 18-mile Elly pipeline and the facilities that operate it were built in the late 1970s and early 1980s, according to the lawsuit.

The pipeline was likely leaking before the damage was discovered Saturday morning, Orange County supervisor Katrina Foley stated over the weekend. Officials from a division of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife stated in a report that they were notified of an "observed sheen" off the Huntington Beach coast at 10:22. p.m. on Friday, according to documents obtained by ABC News.

The U.S. Coast Guard was notified of the leak on Saturday morning, Amplify CEO Martyn Willsher told reporters.

In a letter to Amplify Energy Corp., the U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Material Safety Administration demanded corrective actions to the failed pipeline following the leak. In the letter, the associate administrator for pipeline safety said the oil platform's control room received low-pressure alarms on the San Pedro Bay Pipeline at around 2:30 a.m. PDT Saturday, indicating a possible failure. But the line was not shut down until 6:01 a.m. -- 3 and a half hours later.

Then, "over six hours after the initial alarm and three hours after the company shut down the pipeline, Beta Offshore reported the Accident to the National Response Center (NRC) indicating there was a release of crude oil in the vicinity of its pipeline near Platform Elly," the letter states.

The U.S. Coast Guard submitted a second NRC report at 03:41 p.m. ET, on Sunday reporting oiled marine life and dead fish, according to the letter, and the U.S. Coast Guard submitted a third NRC report later that day, at 05:20 p.m., reporting that the failure may have been caused by a crack in the pipeline.

Officials are looking into whether a ship anchor struck the underwater pipeline, damaging it, Willsher told reporters at a news conference Monday.

The Beta Operating Company has been cited 125 times for safety and environmental violations since 1980, The Associated Press reported, citing a database from the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement. It has been fined a total of $85,000 for three incidents.

Newsom met with Orange County officials Tuesday afternoon and said he supports their calls to shift away from using fossil fuels. He said he will not support new offshore drilling in California.

"This tragedy did not need to occur and does not need to persist into the future," he said.

Newsom said more permits were sought in 2020 to abandon oil drilling sites compared to permits establishing new ones. There hasn't been a new offshore lease in half a century, "and there won't be," he said.

The governor added that more volunteers will be allowed to help with the cleanup as long as they take a four-hour course on proper procedure.

The plaintiffs are requesting a jury trial to determine whether the defendants violated state laws and whether the defendants breached a duty and caused harm to the plaintiffs in the class-action lawsuit. The jury will also be asked whether restitution and compensatory or consequential damages should be awarded to the plaintiffs.

Representatives for the Amplify Energy Corporation did not immediately respond to ABC News' request for comment. Calls to the Beta Operating Company were not answered.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment