Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

We have about twenty big dinner plates and twenty small plates and when was the last time we sat eighteen guests down to dinner in this little apartment? Not since Jesus was in the third grade. I have eight suits in my closet: when did I last get dressed up? The number of unread books on our shelves would sink a pontoon boat. And why the whiskey glasses? Nobody in this household drinks whiskey. Neither do our guests, they’re all left-wing liberals and whiskey, in case you didn’t know it, has become politicized and is now reserved for patriots who are out to Stop The Steal. I wish they’d steal our whiskey glasses.

Two trillionaires, Bezos and Musk, are trying to fly into outer space but you can get away from Earth quite cheaply simply by heading for 80 and 85 when a person starts to feel himself floating in the clouds, unconcerned with so much of what’s going on, such as those hundreds of cars moving at 5 mph down the distant freeway at 7:30 a.m., honking, angry — what is going on with those people? What’s all the fuss about?

The controversy in Nashville over the need for country music to create spaces of healing and equity for people of all identities and to fight oppression of minority points of view, which sprang up after the first nonbinary musicians were featured on the Grand Ole Opry, was interesting but Not My Problem. I love the songs I love and for me country music hit a peak with Loretta Lynn’s “Don’t Come Home A-Drinkin’ (With Lovin On Your Mind),” which was Loretta’s statement of empowerment and anti-oppression in hopes of changing lives and challenging patterns of discrimination so as to bring about evolution of behavior and clearly stating a moral imperative in order to liberate herself from systems of oppression to bring about a sense of authentic belonging and promoting values of mutual respect as an effective tool for social justice rather than perpetuate a structure of male privilege in daily life and mitigate its effects.

The two nonbinary singers, Morgan Newton and Oliver Penn, are demanding that Nashville issue a mission statement pledging to engage in anti-oppressive and inclusivistic musical storytelling that fights intolerance and cultural appropriation, but the way to change the world isn’t to demand change, it’s to write a terrific song as Loretta did. They say that Waylon Jennings’s “Rainy Day Woman” tolerates a structure of male privilege, and maybe it does, but it’s a great song. You disagree, then go write a better one. The Beatles’ first big hit, “Please Please Me,” was exclusionary and disempowering and built on a structure of exploitation, but their harmonies on the line “Come on, come on, come on, come on” made the song irresistible. “I Want To Hold Your Hand” never considered whether the hand, which presumably belonged to a woman, wanted to be held and the line “And when I touch you I feel happy inside” doesn’t consider whether she (or them or it) feels happy inside. You might be offended by the male privilege that’s made all too clear but the song kept running through your head, including the falsetto “OOOOO” and that’s the power of it.

Anyway, it’s an unjust and inequal and often oppressive world out there, and mission statements come flying like autumn leaves, and nonbinary and non-triplicate and quasi-quadrennials struggle for their share of the sunlight, and in Norway people are killing each other with bow and arrow, and the anger of those drivers on the freeway is almost palpable, and I feel some sympathy for all of the troubled, but only some, not a vast amount. I’m 79 and it’s Not My Problem, people. My problem is this computer, which has a bad habit of suddenly going blank and I’ve taken it to be fixed and they told me confiden

If you love your work, be sure not to finish it

The life of a writer is a wild adventure you wouldn’t imagine simply by looking at the lonely figure in the black cloak sitting hunched in her/his niche in the cloister, scratching corrections onto the parchment with a feathered quill pen, but it’s true and someone really ought to write about this. At the moment, I am looking at a galley of a new book of mine as sent by a graphic designer named David and I am stunned by the elegance of it, which makes my own words seem almost of classical quality, which makes me want to revise the work to bring it up to the quality of the design, meanwhile my crew of overseers is firing off memos insisting the book be finished by Friday. This is what I’m up against: David’s graphic artistry has shown me how wonderful my work almost is while editors are banging on the door of my cell, threatening to withhold food until I turn the work over to them. It’s ugly.

The book is set in a small town in Minnesota and I feel that a good street fight, an insurrection of farmers versus townsfolk, with a lot of hacking and clubbing and shouting and cursing, would add some interest and maybe also a good gas explosion. I’ve written many novels and never put a major explosion in one and it’s appealing to me now, the chance to have people I dislike file into a building and then blow it up. Terrorists do this all the time, so why not novelists?

It occurs to me, too, that my previous graphic designers were named Butch, Buddy, and Misty, and their surnames ended with -sen or -quist, and David’s name ends with a vowel, same as Caravaggio, Michelangelo, and Fra Angelico, and my literary reputation has been hampered by poor page design and bad taste in fonts. I think that with the addition of an insurrection and a gas explosion I could break out of my reputation for Midwestern nostalgia and be taken seriously by critics for the Times and Post who majored in women’s studies at Bryn Mawr and Smith, especially if the old white reactionaries who stage the insurrection are the ones who file into the building that minutes later goes up in a cloud of flame and smoke, but meanwhile I’m in the hands of deadline enforcement officers who want me to stop and hand over the goods.

Did Dostoevsky work under these conditions? James Joyce? Toni Morrison?

The real problem, however, is not only artistic but also my fear of finishing the book and dreading the onset of leisure time, which, in old age, only leads in one direction, brooding, mental deterioration, half-pound cheeseburgers, and watching MSNBC and Rachel Maddow, which leads to despair for the republic. I’ve spent the past year ensconced in fiction and was very happy most of the time. (I’ve never heard Rachel Maddow use the word “ensconced,” by the way. She might say “hopelessly trapped” or “barricaded” but “ensconced” is too comfy for her and she is not a creature of comfort.)

When the enforcers take possession of my hard drive and publish the novel, minus the clubbing and hacking and the gas explosion, I plan to take charge of my life and announce to my wife, who formerly was in charge of it, “My darling, I’m done with Manhattan. We’ve owned this apartment for twenty years and real estate values are skyrocketing and let’s clean up and move to Portugal.”

We spent a week in Portugal a couple years ago for her nephew’s wedding and we loved it. They are a sensible people, fishermen, farmers, sailors, explorers. When I told the nephew how I admired his wife’s ability to adapt to American culture and make friends and find her way around, he said, “Well, she’s Portuguese. She passes for Parisian but she’s her parents’ daughter.” Her father Antonio is an olive rancher and all-around handyman who stayed up all night dancing at the wedding and then drove us around the olive plantation showing off his trees and talking a blue streak in Portuguese. He is a happy man and keeps busy managing twenty or so unfinished projects. He’s a few years younger than I but he’s my model. I want to settle in his village and go to work writing unfinished novels.

A writer doesn’t need literary prizes to be happy, happiness lies in the work itself, sitting down in the niche with the quill pen and adding a few more curlicues. I am ensconced in my work. I don’t want to lose it and that means postponing publication as long as possible. They don’t teach this to MFA students but they should.

A few beams of light on our current situation

“Goodness gracious” was about as close as my mother came to actual profanity, that and “Oh fudge,” and now that our daily life is showered with profanity and obscenity, it is no more shocking than dog barks, whereas the words “Goodness gracious” still have (for me) a bite to them, and I can feel my mother’s dismay, which now I feel, hearing about the tidal wave of political narcissism opposed to the idea of social responsibility — Senator Graham was booed and harassed the other day by constituents when he suggested they consider getting vaccinated against COVID — people who deny that the state has a right to mandate vaccination or mask-wearing as a public health measure or enforce speed limits or restrain the sale of weapons meant for combat or the responsibility of parents to send their kids to school, and weird ideas that are being preached from pulpits by ministers who don’t realize that their own people are dying of COVID and in marginal states the plague may be delivering the 2022 elections to us socialists. To raging narcissism, I say, “Oh fudge.”

Nonetheless, I am happy. October has that effect on me and it’s heightened by sunny days and the fact that the suffering of us Minnesota Twins fans is at an end as we go into the postseason and last week we had the pleasure of seeing the plutocrat Yanks squashed by Boston, players who are up in Mark Zuckerberg’s pay bracket and who couldn’t buy a hit or even draw a walk. I am not proud of taking pleasure in the suffering of multimillionaires but it’s a long-standing American tradition. The Yankees’ star right fielder Aaron Judge said, “To me, it’s black and white. Either you win or lose. We lost.” Which, for a guy who could afford to hire a writer, or content provider, is not a memorable line, not even in the ballpark. Casey Stengel who earned a tiny fraction of Judge’s salary said, while managing the Mets, “You look up and down the bench and you have to say to yourself, ‘Can’t anybody here play this game?’” A great line and I’ve thought of it often in my life.

I thought of it a few hours before the game when I tried to sign up for ESPN so I could watch it and I had to use the round clicker on the remote to write. I am a guy from the Three Network era back just after the Civil War when ABC, CBS, or NBC would’ve carried the game and all I had to do was open a bottle of beer, but now I have to manipulate this weird device and after three failed attempts I called my wife on FaceTime and we struggled to get it done and there was some yelling but the marriage survived and I got to see the pinstripe guys slump off the field while the Red Sox danced and whooped and the fans were delirious in the Fenway stands, though surely they knew that this team will likely break their hearts as it has so often in the past.

“Can’t anybody here play this game?” comes to mind when I read about Congress and the debt ceiling hassle and the Republicans’ aversion to talking about climate change even as the reality of it is rather clear and auto manufacturers are planning for electric car production, but Republicans are satisfied with a policy of denial. This is not intelligent but they believe it’s a winning strategy. Goodness gracious. Who are these people? What game are we playing?

With my team packed up and gone home, I’m free to spend October with a light heart. This is the advantage of defeat: the dreadful anticipation of it is over, you got skunked, and you discover defeat is a sort of liberation. But Washington is another matter. The South lost the Civil War but went on to win the 20th century and today we’re living in a confederacy. We have a Confederate Supreme Court and soon will likely have a Confederate Congress. My mother was of a Depression generation that didn’t tolerate narcissism but here we are. But as Casey almost said, “The Democrats have shown me more ways to lose than I ever knew existed. They say there’s always hope, but sometimes that doesn’t always work. But never make bad predictions especially about the future.”

Lonely guy seeks old café and three buddies

I am an orphan, which is not so unusual for a man of 79, and like everyone else I know, I work out of my own home and at the moment I’m sitting at the kitchen table with a bowl of Cheerios beside the laptop and a cup of coffee (black). I have no office anymore. I’ve had offices, not cubicles but offices with doors and a window, sometimes a credenza, since I was 22 years old. I miss them.

If someone opens a Museum of the American Office, I volunteer to be a docent and I’ll show them around the office of fifty years ago with the mimeograph machine, the manual typewriter, and the big telephone with the long curly cord that went into the wall. There was no copier, we used carbon paper. Someone knocked on the door and I hid my copy of Portnoy’s Complaint in the top drawer and a woman poked her head in and said, “The meeting is about to begin.”

That’s what I miss, the meeting. They were like little morality plays, in which people assumed allegorical roles, Dreamers, Realists, Satirists and Strategists, and the outcome was usually to maintain inertia but they were entertaining. I was a satirist in my early years and then suddenly I became the boss and I was surrounded by realists, and at the end of my office career, I became a dreamer and the two women employees listened and took turns being the assassin who points out the deadly reality so not much happened but I was okay with that. The pleasure was in the meeting itself.

We cleared out the office because we didn’t need it, the copier went, the coffeemaker, conference table, the files were packed off to Deep Storage (where we’ll all wind up someday), and we went home.

Electronics made the office redundant, no need to be combed and suited up by 9 a.m. I imagine the Oval Office may be only a ceremonial room and Joe, though still the most powerful man in the world, may be working from his breakfast table in his T-shirt and pajamas like me. Maybe the Supreme Court will decide to go on conferring by Zoom, the justices at home in their judicial bathrobes.

But I miss it, those friendly Good Mornings as I, Mr. Boss Man, walk in. My wife says Good Morning but sometimes she also says, “You really need to do something about your hair. And your eyebrows. My gosh. How do you see through those things?” My employees never said that.

So now I sit at a laptop at my kitchen table, still in pajamas at noon, and I compose limericks like:

The poet Sylvia Plath

Suffered depression and wrath:

The day that she dove

Headfirst in the stove,

She should’ve just had a hot bath.

A man doesn’t need a staff to sit around a conference table and help him write five-line limericks. But it’s lonely and there’s a loss of status. When you can no longer say, “I have a meeting at the office this morning” people put (Ret.) after your name, and I don’t want that. I’ve thought of about getting myself a psychotherapist just to have someone to meet with and talk about stuff but I’d be trying to amuse her, which is my line of work, and she’d be probing for the dark dank cellars of my unconscious though there truly are none, I’ve looked, and my unconscious has no basement, it’s a solid concrete slab, nothing mysterious about it. I have friends who are in the therapy business and they listen much too closely and the way they say “Hmmm” and “Oh really?” makes me uneasy.

So I’m trying to get together some men to have lunch with. I’ve got one guy, a former Republican, formerly in the investment biz, a guy who turns to the sports page first thing every morning. He’s perfect. Now I need to find two more sort of like him. I’m a Democrat so I’d like a Republican and maybe a guy who knows about science. Race and ethnicity don’t matter. Two guys over forty. Nobody in the arts. If we met this morning, I’d look through my enormous eyebrows and tell about two lively small towns in Pennsylvania I saw this weekend, Sellersville and Jim Thorpe, and how walking around in them made me love this country more than ever. Someday I’ll find my group. Oyster stew and a grilled cheese. Coffee. Looking forward.

An ambulance brings a man to the hospital. (photo: Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images)

An ambulance brings a man to the hospital. (photo: Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty Images)

Gaige Grosskreutz, poses for a portrait at a park in Milwaukee on Sept. 26, 2020. Grosskreutz, who attended close to 100 nights of Black Lives Matter protests, lost part of his right biceps after being shot by Kyle Rittenhouse at a protest in Kenosha, Wis., but survived. (photo: Lauren Justice/WP)

Gaige Grosskreutz, poses for a portrait at a park in Milwaukee on Sept. 26, 2020. Grosskreutz, who attended close to 100 nights of Black Lives Matter protests, lost part of his right biceps after being shot by Kyle Rittenhouse at a protest in Kenosha, Wis., but survived. (photo: Lauren Justice/WP)

Gaige Grosskreutz, 27, filed the lawsuit Thursday in federal court in Milwaukee, just weeks before Rittenhouse’s murder trial is set to begin. It marks the second major legal action against the city and county of Kenosha since the Aug. 25, 2020, riot where Rittenhouse shot three people: Grosskreutz, who lost a chunk of his biceps but survived; Joseph Rosenbaum, 36, and Anthony Huber, 26, who both died.

Rittenhouse, 18, whose trial is set to begin Nov. 1, faces homicide charges in both deaths and an attempted homicide charge for shooting Grosskreutz as well as a charge for being a minor in possession of a firearm. Rittenhouse has pleaded not guilty to all charges and his attorneys are expected to argue that he acted in self-defense.

Grosskreutz’s complaint names both the city and county, which oversee their respective law enforcement agencies, as defendants. Kenosha Police Chief Eric Larsen, Kenosha County Sheriff David Beth and former Kenosha police chief Daniel Miskinis are individually named as well. It seeks a jury trial as well as unspecified punitive and compensatory damages.

Attorneys for the municipal agencies did not immediately respond to requests for comment Saturday. Attorney Sam Hill, who is representing Beth, rejected allegations in the lawsuit as false and said in a statement to multiple media outlets he would move to have the complaint thrown out.

The suit focuses heavily on law enforcement’s response in August 2020 when Kenosha had been gripped by protests — and later, riots — in the days after a White Kenosha police officer shot Jacob Blake, a now-30-year-old Black man. Officer Rusten Sheskey shot Blake at least seven times in the back as Blake was getting into his car; three of Blake’s children were present. The shooting damaged Blake’s stomach, kidney and liver, required removal of most of his small intestines and his colon and left him paralyzed from the waist down. The Justice Department recently declined to bring charges against Sheskey.

Grosskreutz was in Kenosha protesting the police response, which included firing tear gas and rubber bullets on demonstrators. The lawsuit contrasts that response with the way police treated White counterprotesters, even when the White protesters were armed.

The complaint opens with words a law enforcement officer spoke to Rittenhouse that night: “We appreciate you guys — we really do.”

“These were the words of Kenosha law enforcement officers — words of encouragement, appreciation, and thanks, spoken to Kyle Rittenhouse and a band of white nationalist vigilantes on the evening of August 25, 2020,” the complaint states.

According to cellphone video of the scene, Rosenbaum and Rittenhouse appear to argue, and Rosenbaum throws a plastic bag at the teen while running after him. An eyewitness said Rittenhouse was pointing his gun toward Rosenbaum and shot him after Rosenbaum tried to lean in and grab the gun.

After Rittenhouse fled the scene, protesters and other bystanders who eventually identify him as the shooter begin to chase him. Huber and Grosskreutz are among those pursuing Rittenhouse, who trips and falls as he tries to run. From the ground, he fires at Huber, who is holding a skateboard, and then shoots Grosskreutz as he approaches.

Grosskreutz told CNN last year that he believes in the right to peacefully protest and bear arms — which he said he did legally, unlike Rittenhouse, who was too young at the time to legally possess a dangerous weapon. Rittenhouse was 17 at the time.

“Nobody should have been hurt or died that night,” he said. “I never fired my weapon that night. I was there to help people, not hurt people.”

The complaint alleges police allowed Rittenhouse to walk away after shooting three people, making no effort to arrest, disarm or even question him. Officers did not stop the teen even as he approached them with his hands up after the shooting.

“The only reason Defendants allowed Rittenhouse to walk away after shooting three people was because he was white and because he was affiliated with their compatriots, who had Defendants’ explicit support,” the complaint said.

The night of the riots, Rittenhouse drove 20 miles from Antioch, Ill., to Kenosha, armed with an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle. He was allegedly prompted by a call-to-action via a Facebook group calling itself the Kenosha Guard. Former Kenosha city alderman Kevin Mathewson, who helped organize the action, wrote in the call out for neighbors to “take up arms to defend our City tonight from the evil thugs.”

The Kenosha Guard later denied having any affiliation with Rittenhouse. Mathewson told The Washington Post the day after the 2020 shooting that he was calling on citizens to protect residences and property and that law enforcement on the scene had a “positive” reaction to the citizen mobilization.

“They were handing out water to some of us, thanking us and greeting us very warmly,” he said at the time.

Claims in Grosskreutz’s case echo those in the lawsuit Huber’s family filed in August alleging that the city and its police and county sheriff’s departments openly conspired with White militia members, which gave them “license … to wreak havoc and inflict injury.” If Rittenhouse were Black, the complaint from Huber’s family reads, the “defendants would have acted much differently.”

A general strike. (photo: Left Voice)

A general strike. (photo: Left Voice)

In a recent opinion piece, former U.S. labor secretary Robert Reich argues that the September jobs report shows evidence of an “unofficial national general strike.” But that is a contradiction in terms.

While conservatives wring their hands over how big government spending on benefits is incentivizing people not to return to work now that the bosses and politicians decided the pandemic is over, Reich offers another explanation for the “labor shortage.” Pointing to high numbers of workers quitting their jobs each month, and to the numbers of people “in their prime working years” leaving the workforce entirely, Reich sees these trends as a sign that after a year and a half of pandemic lockdowns, layoffs, lack of childcare, and increased precarity, workers are less willing to accept the low wages, inadequate or nonexistent “benefits,” and long hours their employers offer. This is particularly evident in the tourism and logistics sectors, such as hotel work and trucking, both of which report hiring difficulties and are not rebounding as fast as economists predicted. He writes:

Corporate America wants to frame this as a “labor shortage.” Wrong. What’s really going on is more accurately described as a living-wage shortage, a hazard pay shortage, a childcare shortage, a paid sick leave shortage, and a healthcare shortage.

Here Reich is correct. There’s no shortage of labor, but rather the conditions of that labor have become — or in many cases already were — untenable. As even Reich admits, this is not a new problem, nor one that can be explained solely by the pandemic. In response to years of attacks on their living conditions that were then exacerbated (or brought into stark relief) by the pandemic, an increasing number of workers have decided they will no longer put up with the ways they’ve been required to work for the last several decades. “Many just don’t want to return to backbreaking or mind-numbing low-wage shit jobs,” Reich writes.

But workers aren’t just “fed up.” Most people don’t have a choice. Many can no longer work under the conditions they faced before the pandemic, especially now that the capitalists’ response to the pandemic has made it all the more likely that the pandemic and its effects will extend for years to come. For example, lack of access to childcare has effectively forced hundreds of thousands of people — most of them women — out of the workforce for the foreseeable future. According to the most recent jobs report, more than 300,000 women left the workforce in the last month, many citing lack of childcare. So while there may very well be plenty of open jobs, such as in the service industry, many people can’t afford to pay for childcare on the low salaries that have become standard in those sectors.

And it’s not just childcare. As a National Low Income Housing Coalition report stated this July, no one working full time at a minimum-wage job can afford rent for a two-bedroom apartment anywhere in the country. Millions of people in the United States can’t afford to pay their utility bills, and energy prices are only expected to rise this year. It’s not that people are simply “rethinking the way they work” after a year and a half of the pandemic, as many opinion columnists would like us to believe; many people cannot continue to work under the same pre-pandemic conditions. Many see no other choice than to drop out of the workforce to take care of loved ones or to seek higher-paying, less-demanding jobs.

Yet in the hundreds of thousands of workers quitting or not actively seeking work, Reich sees a sort of “disorganized” resistance to the pre-pandemic status quo. He writes, “American workers are now flexing their muscles for the first time in decades. You might say workers have declared a national general strike until they get better pay and improved working conditions.” He even goes so far as to put this on par with the tens of thousands of workers currently on strike, or about to strike, across the country, from the 60,000 IATSE workers in the entertainment industry who just announced a tentative strike date after a 98% strike authorization vote, to the 10,000 John Deere workers who just went on strike in three states, to the Kellog’s workers on strike in four states, to the Warrior Met coal miners who are entering the seventh month of their strike.

But let’s be clear: hundreds of thousands of people individually leaving the workforce or quitting their jobs isn’t any type of strike, unofficial or not.

It is a response to the same factors that have forced workers across the country to stand together and go on strike for better conditions, but characterizing it as a strike misses an essential part of what gives a general strike its power: the ability of workers to organize themselves across sectors to withhold their labor and bring capitalist production to a halt, collectively, on a large scale. A “disorganized” strike is a contradiction in terms. In ignoring this, Reich glosses over what could actually bring about the changes workers so desperately need — and for which many workers are already fighting.

Contrary to Reich’s claims, individuals leaving the workforce in droves and hoping that employers will raise wages as incentives to come back doesn’t exactly give all workers the best “bargaining leverage” to fight for better working conditions. It’s true, as Reich points out, “Average earnings rose 19 cents an hour in September and are up more than $1 an hour – or 4.6% – over the last year.” The bosses are feeling the pressure of unfilled positions and are making some concessions in an effort to boost hiring. Large companies and local governments that can take the hit are even offering sizable, one-time “signing bonuses” to lure workers back into the workforce.

But these are only temporary concessions that allow the bosses and the state to set their own terms, offering just enough to entice workers back — or starve them until they have no choice but to return. But more importantly, they leave workers without the strength to fight for what they deserve and protect themselves when the bosses look for ways to squeeze them later. What really gives workers leverage is their ability to stand together, withhold their labor, and organize themselves to fight for their demands — and potentially so much more.

Of course, Reich isn’t really interested in workers recognizing the full potential of their strategic position in society. In fact, the ruling class and its mouthpieces much prefer workers confronting the systemic issues that face them as a class individually, rather than organizing for their rights together in unions and striking until they get what they deserve. Ultimately, though it may be cloaked in progressive language about workers’ power, Reich’s analysis is a thinly veiled warning to the bourgeoisie: if capitalism is to continue relatively unchanged, then the powers that be must offer the working class some concessions to preempt more class struggle later. And that’s a door the ruling class doesn’t want to open.

After all, it was a general strike in 2019 in Chile that grew from explosive protests over rising subway fares into nationwide class struggle that saw the rise of workers’ health and safety committees and ultimately a constitutional convention to draft a new constitution.

Just a few months later in Ecuador, a general strike and mass protests forced the government to backtrack on its plans to cut fuel subsidies, which would have doubled the price of fuel, and forced the government to seek a restructuring deal. In the process, they denounced the catastrophic foreign debt and the IMF.

Just this year, workers organized in unions were at the forefront of resistance to the military coup in Myanmar. They came out in millions across the country to defend their rights and defy the junta.

These are “official” national general strikes, and they show just how much power the working class has when it organizes itself to fight back against the capitalist state using its own methods.

Thousands of workers currently leaving the workforce each month doesn’t get the working class any closer to building this type of power. Contrary to what Reich would have us believe, the fact that many workers see no other alternative is not a sign of the strength of the working class in the current moment, but its weakness. It is an expression of and adaptation to the attacks on unions over the years and the collaborationist policies of the union bureaucracies that pull every maneuver possible to avoid a fight and make nice with the bosses. Only 11 percent of U.S. workers are unionized, leaving the vast majority without a clear path to fight for their interests collectively. Added to this is the fact that the 14.3 million workers who are in unions are pacified by union leaders who are in the pockets of politicians and the bosses, refusing to put up little more than symbolic fights. Again and again they move to deprive workers of their greatest weapon against the bosses — the strike. They agree to contracts with “no strike” clauses and the prohibition of solidarity strikes. They half-heartedly threaten strikes, only to pull out at the last minute. They use union financial resources that could go towards strike funds on their bloated salaries and to make campaign contributions to capitalist politicians. In short, they do everything possible to undermine the participation of rank-and-file workers in a fight to defend their own interests.

It’s no wonder that many workers see no alternative but to quit their jobs. But recent rumblings in the labor movement offer a spark of hope that could light the way ahead. We see this in recent union drives in the tech industry and elsewhere. And nowhere is this more clear than in the tens of thousands of workers currently walking picket lines across the country. But for these recent labor struggles to build into a towering wave capable of winning much-needed concessions for the working class, workers need to put their collective power into audacious fighting strategies that challenge their misleaders and build the power necessary to turn this “unofficial” national general strike into an official, unstoppable one.

Imagine if the 60,000 IATSE workers preparing to strike this month tied their own demands for higher wages to the fight of Kellog workers to get rid of the two-tier wage system, and to the demands of 10,000 John Deere workers for bigger raises. This could pave the way for other sectors to join them, such as Amazon workers breaking their backs for $15 an hour. Imagine Uber and Lyft drivers, who take home a fraction of what they earn for those companies each day, were to walk off the job as well; or if restaurant workers, working more hours for less pay after a year of shutdowns, were to walk out. Banding together, these workers could win so much more than pay increases for individual contracts in individual workplaces. They could demand better working conditions for all workers, unionized and unorganized, employed or unemployed. They could demand a rise in the minimum wage to one that actually reflects the cost of living. They could put an end to the disastrous two-tier wage systems that pit workers against each other. They could demand free and universal healthcare, child care, and housing.

That is the power of the general strike. It is a weapon the working class will have to wield if we want to make the capitalists pay for the crisis they’ve created. We need a massive, organized workers’ struggle that can fight for our demands — to the end.

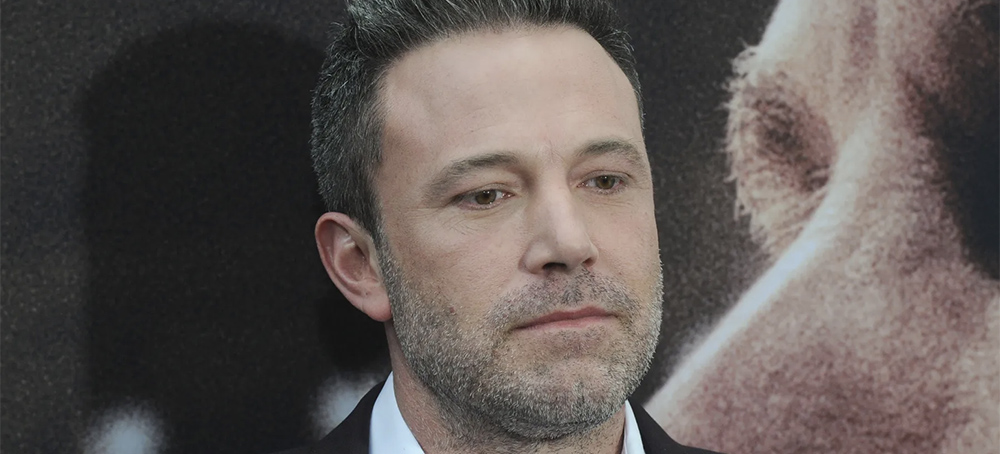

Ben Affleck at the premiere for The Way Back, Regal LA Live, March 1, 2020. (photo: Albert L. Ortega/Getty Images)

Ben Affleck at the premiere for The Way Back, Regal LA Live, March 1, 2020. (photo: Albert L. Ortega/Getty Images)

The app has created a space free of the problems that plague the rest of the Web, but only by leaving almost everybody out.

In truth, Jay needn’t have worried that Affleck’s profile was false advertising. Raya is the rare social network that insures that all of its users are who they say they are. Since it launched, in Los Angeles, in 2015, it has gained a reputation as the “celebrity dating app” and “Illuminati Tinder.” Impersonation isn’t tolerated, nor is anonymity, much less any form of harassment. The app is private; aspiring users must undergo an application process that can stretch on for months. (One applicant recently reported that she was approved after a wait of two and a half years.) Demi Lovato, Channing Tatum, John Mayer, Lizzo, Cara Delevingne, and Drew Barrymore have all reportedly been members. Nicholas Braun is a stalwart. Simone Biles met her boyfriend, an N.F.L. player, on the app. Once accepted, members must adhere to a rigid code of silence—no exposing other people’s profiles and no screenshotting within the app. Even tweeting too much about Raya, or publicly mentioning another member, can be grounds for a ban. Which means that Jay’s peak moment on the app was also her last. After she posted Affleck’s video on TikTok, the company quickly kicked her off. “Our decision is final,” the fateful message to rule breakers reads.

Such strict regard for privacy is, of course, vanishingly rare in the world of social media. A recent investigative series in the Wall Street Journal helped illuminate how Facebook—which is used by nearly three billion people each month—exploits its stores of personal data to serve content that may be detrimental to its own users. We’ve become accustomed to the public exposure and punitive chaos of social media. It’s hard to conceive of it working any other way. At the same time, smaller-scale and less automated platforms have gained ground, offering the promise of refuge. Discord, an app for real-time chats that supports more than nineteen million active communities, creates silos for users based on topics of interest. E-mail newsletters on platforms such as Substack are forming digital communities that are often closed to nonsubscribers, with comment threads serving as D.I.Y. discussion boards. Even Instagram’s Close Friends feature allows users to regulate who can see particular posts. But Raya, which has grown consistently in the past six years, is perhaps the most successful experiment yet in the search for safer, gentler, more private forms of social networking. The company’s vice-president of global membership, Ifeoma Ojukwu, told me that Raya is interested in the challenge of “scaling intimacy.” She added, “By no means are we trying to be for everyone.”

Raya’s founder, Daniel Gendelman, rarely grants interviews, but he met me recently at La Mercerie, an influencer-friendly café in SoHo, to discuss his vision for the company. He wore jeans and a monochrome T-shirt with a thin chain necklace—hipster-entrepreneur chic—and exuded an air of calm curiosity. (“If you were to just hear the phrase ‘founder of Raya’ in a vacuum, you would assume the guy is a tremendous douchebag,” one member told me. “But Dan is surprisingly earnest.”) Sitting on a turquoise velvet sofa, Gendelman recounted Raya’s origin story. In 2014, he had landed in Tel Aviv, in the aftermath of a startup implosion. He was looking to connect with other young people there but became frustrated with apps like Tinder, where the focus is on dating or hooking up. A different kind of app could facilitate networking and friendship as much as romance, Gendelman thought. He looked around us at the downtown café-society scene. “There are thousands of tables just like this, with people with good intentions who care about the world, who want a safe, exciting place to communicate,” he said.

In Los Angeles, in 2015, Gendelman launched Raya (in Hebrew, the word means “wife” or, in its masculine form, “friend”) out of his apartment in West Hollywood. Most social-media platforms rely on selling ads. Raya, instead, charged a subscription fee of $7.99 per month (now $9.99). At the time, dating apps still carried something of a stigma, but Raya’s veneer of curation and privacy set it apart. TJ Taylor, an early employee, recalled his in-box being flooded with invitation requests. “You needed to be on Raya—if you weren’t, you were severely missing out and looked at as a social outcast,” he said. The app’s popularity was driven by FOMO—the sense that whatever was happening behind the curtain was better than anything happening in public. Gendelman told me that he recalls some observers grumbling that the famous names spotted on the app must be paid placements. “We never asked a celebrity to join, ever,” he said. On the contrary, the fuss over celebrities online dating obscured the app’s more mundane goal which, according to Gendelman, was to develop a kind of curated LinkedIn, a space that would foster creative-industry collaboration and companionship.

That model seemed to hold even greater potential with the advent of the pandemic, when social networks became vital tools for communicating in isolation. In 2020, Raya added a series of new features including its Directory, a kind of bespoke Rolodex that allows members to search one another by city, industry, or company (W.M.E., for example, or Uber). You can find a Raya-approved architect or graphic designer to plan a renovation or make a portfolio. According to the company, the Directory has seen more than a million searches to date. Raya’s increased emphasis on work might be less a pivot than a reflection of how, for a millennial clientele, love, careers, networking, and identity formation often flow seamlessly together. Erotic capital intermingles with economic capital. Two perfectly curated lives frictionlessly intersect. “In the age of everybody having a personal brand, Raya’s the place where people compare personal brands,” one former Raya user told me. (He was kicked off the app for tweeting about it but requested anonymity for this piece, because he had hoped to get back on.)

“Networking through LinkedIn is too cold,” Edith Vaisberg, an art adviser and curator living in Mexico City, told me. “You follow a lot of people on Instagram—it doesn’t mean you want to get it on with all those people.” Vaisberg initially joined Raya for dating but turned to it again, in the early months of the pandemic, and discovered that it was a place to connect with potential clients in the absence of the usual art-world travel circuit. She recalled connecting on Raya with a painter she’d long wanted to meet. Another time, she went to a barbecue at the home of a guy she met on Raya and met two of his friends with whom she’d already matched on the app. Neel Shah, an L.A.-based screenwriter who joined Raya in 2015, described the membership as “people you wouldn’t have known to invite to your dinner party, but, if they showed up, you would have been happy they were there.”

Raya wouldn’t disclose the size of its user base, but a spokesperson told me that it expects to receive its millionth application by the end of 2021, and is on track to reach four hundred thousand this year alone. The company likes to play down its exclusivity, but its admission rate is in the single digits. The rigorous selection process and ongoing community maintenance require expensive staff commitments. Facebook outsources the majority of its content moderation to outside contractors. At Raya, by contrast, a quarter of the forty-person staff is devoted to application review and community support. Prospective members are evaluated based on their existing digital imprints and social connections. Eighty-seven per cent of successful applicants are referred by existing members or have Raya members among their phone contacts. Those who have exhibited disrespectful behavior elsewhere on the Internet are automatically disqualified. Like an élite college, Raya accepts, rejects, or wait-lists its applicants; every application gets a personal response, as does any complaint or query from an active member. Gendelman noted that, elsewhere online, “You can watch people partake in screaming at another person, saying really nasty things, and that’s just accepted.” Again, he offered the café we were sitting in as a metaphor: “If I did that to the people at the table next to us, I’d get thrown out.” Nivine Jay, Ben Affleck’s erstwhile target, recalled a Raya date with a man who became aggressive. “I messaged Raya, and they kicked him off immediately,” she said.

Last month, Raya granted me access to a temporary account. Just like that, I was in. The app’s interface resembled a combination of Instagram, iMessage, and Airbnb with people in place of apartments. A Maps page showed who was active in my city. The Directory feature presented a continuously sliding scroll of search suggestions that seemed pregnant with lucrative networking potential: “Members in Public Relations,” “Members at YouTube,” “Art Directors.” Backdrops of soothing stock photography showed abstract patterns, hotel interiors, vistas of nature. I encountered the profiles of well-known journalists, actors, athletes, and a slew of consultants and marketers. Some had set their preferences to “here just for friends.” (According to Raya, ten per cent of profiles use that setting.)

What seemed to tie everyone together was a fluency in digital media, a consolidation of identity online. A central feature of each profile is a slideshow set to a chosen song clip. Instead of haphazard selfies, the slides often included professional headshots and stills from television appearances. The images did not dispel Raya’s reputation as an app primarily for hot people. Similar to dating apps like the League, Raya wards off the ennui of endless scrolling by limiting the number of profiles users can check out each day. Whether you’re looking for romantic or professional collaboration, you still tap a check mark or an “X” button to accept or reject each match. One profile I matched with, belonging to a designer of 3-D-printed lingerie, formed a kind of holistic life-style portfolio, with product photo shoots and in-progress fabrications interspersed with selfies. I couldn’t tell whether she was looking for a date or a design commission.

Tapping around the app, I felt a bit like I was walking through a cocktail party I hadn’t been invited to, and was in violation of the dress code. Facebook and Twitter thrust you into a dramatic collision with vast numbers of strangers, but Raya ushers you into a walled garden of the Internet, where the already well-connected can connect free of worries. The result is an unsettling kind of homogeneity, reminiscent of Facebook’s early days as a network exclusively for Ivy League students—an élite group further solidifying itself online. Gendelman spoke to me in lofty terms about Raya’s success at solving the problems that plague other parts of the Web. “Social networking is not a term we want to use. It really needs to be a community,” he said. But community is always for a limited number of people, a small group of insiders separated from a much larger group of everybody else. At a certain point, intimacy is no longer scalable. A private social-media platform like Raya can certainly be safer. It is also by nature less open and more stratified than we’ve come to expect social networks to be. The future may look more like hundreds of Rayas, each with its own paying members and rigorous community regulation. But those users who don’t fit the mold or can’t pay may be left outside the walls, to continue living in a digital landscape that looks even worse than it does now.

Myanmar's military government chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who overthrew the elected government in a February 1 coup, presides over an army parade on Armed Forces Day in Naypyidaw, Myanmar, on March 27, 2021. (photo: Stringer/Reuters)

Myanmar's military government chief Senior General Min Aung Hlaing, who overthrew the elected government in a February 1 coup, presides over an army parade on Armed Forces Day in Naypyidaw, Myanmar, on March 27, 2021. (photo: Stringer/Reuters)

The decision taken by foreign ministers from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) at an emergency meeting on Friday night was an unusually bold step for the consensus-driven bloc, which traditionally favours a policy of engagement and non-interference.

Brunei, ASEAN's current chair, issued a statement citing a lack of progress made on a roadmap that the junta had agreed to with ASEAN in April to restore peace in Myanmar.

Singapore's foreign ministry said on Saturday the move to exclude junta chief Min Aung Hlaing was a "difficult, but necessary, decision to uphold ASEAN’s credibility".

A spokesman for Myanmar's military government blamed "foreign intervention" for the decision.

Junta spokesman Zaw Min Tun told the BBC Burmese news service that the United States and representatives of the European Union had pressured other ASEAN member states.

"The foreign interventions can also be seen here," he said. "We learned that some envoys from some countries met with U.S. foreign affairs and received pressure from EU."

An official junta statement on Sunday morning said ASEAN's decision went against its longtime central principle of consensus.

"Myanmar is extremely disappointed and strongly objected the outcomes of the Emergency Foreign Ministers’ Meeting as the discussions and decision on Myanmar’s representation issue was done without consensus and was against the objectives of the ASEAN, the ASEAN Charter and its principles," it said.

More than 1,000 civilians have been killed by Myanmar security forces with thousands of others arrested, according to the United Nations, amid a crackdown on strikes and protests which has derailed the country's tentative democracy and prompted international condemnation.

The junta says those estimates of the death toll are exaggerated.

ASEAN chair Brunei said a non-political figure from Myanmar would be invited to the Oct. 26-28 summit, after no consensus was reached for a political representative to attend.

"As there had been insufficient progress... as well as concerns over Myanmar’s commitment, in particular on establishing constructive dialogue among all concerned parties, some ASEAN Member States recommended that ASEAN give space to Myanmar to restore its internal affairs and return to normalcy," Brunei said in a statement.

It did not mention Min Aung Hlaing or name who would be invited in his stead.

Brunei said some member states had received requests from Myanmar's National Unity Government, formed by opponents of the junta, to attend the summit.

'JUSTIFIED DOWNGRADE'

ASEAN has faced increasing international pressure to take a tougher stand against Myanmar, having been criticised in the past for its ineffectiveness in dealing with leaders accused of rights abuses, subverting democracy and intimidating political opponents.

A U.S. State Department official told reporters on Friday that it was "perfectly appropriate and in fact completely justified" for ASEAN to downgrade Myanmar's participation at the coming summit.

Singapore in its statement urged Myanmar to cooperate with ASEAN's envoy, Brunei's second foreign affairs minister Erywan Yusof.

Erywan has delayed a long-planned visit to the country in recent weeks and has asked to meet all parties in Myanmar, including deposed leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who was detained in the coup.

Junta spokesman Zaw Min Tun said this week Erywan would be welcome in Myanmar, but would not be allowed to meet Suu Kyi because she is charged with crimes.

Malaysia's foreign minister said it would be up to the Myanmar junta to decide on an alternate representative to the summit.

"We never thought of removing Myanmar from ASEAN, we believe Myanmar has the same rights (as us)," foreign minister Saifuddin Abdullah told reporters according to Bernama state news agency.

"But the junta has not cooperated, so ASEAN must be strong in defending its credibility and integrity," he added.

Robert Thurman Jr., his daughter Robriana Thurman and his sisters Candence Thurman, Gail Thurman, Henrietta Thurman and Candace Thurman wait on Robert Thurman Sr. as he works a field in Pembroke Township. (photo: Rashod Taylor/ProPublica)

Robert Thurman Jr., his daughter Robriana Thurman and his sisters Candence Thurman, Gail Thurman, Henrietta Thurman and Candace Thurman wait on Robert Thurman Sr. as he works a field in Pembroke Township. (photo: Rashod Taylor/ProPublica)

At least 18 threatened or endangered plant and animal species, including the ornate box turtle and regal fritillary butterfly, have been sighted here. Mature oaks tower over verdant fields of clustered sedge and Carolina whipgrass. Warbling songbirds and buzzing cicadas add a mellow soundtrack to the tranquil scene.

Sixty miles south of Chicago, this wildlife reserve is among nearly 2,900 acres owned by private individuals and environmental groups — most prominently, The Nature Conservancy — trying to establish a network of nature sanctuaries in Kankakee County. Their efforts have overlapped with those of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which two decades ago put forward a plan to buy up and preserve thousands of acres of what conservationists consider a rare habitat, one that includes the nation’s largest and most pristine concentration of sandy black oak savanna.

But these well-intended efforts overlooked a key consideration: the support of the residents of Pembroke and surrounding areas. Across the region, the acquisition of land by both the federal government and private conservationists occurred — and planning for more continues — in the face of persistent objections from local communities, including residents of this longtime Black farming community.

Founded by formerly enslaved people and later a haven for Black Southerners fleeing racial violence during the Jim Crow era, Pembroke became renowned as a symbol of Black emancipation and touted as one of the largest Black farming communities north of the Mason-Dixon Line. In its heyday, farmers and ranchers here not only raised their own food but supplied fresh produce to Kankakee and Chicago. Today, a small number of Black farmers are trying to hang on to what little they have left, while other parts of the township have struggled as well, with loss of jobs, a declining population and a crumbling village hall.

Some land for these nature sanctuaries was purchased at county auctions after local residents fell behind on their property tax payments, or from outsiders who picked up the delinquent parcels and flipped them, raising echoes of predatory practices that have long plagued Black landowners.

Adding to the opposition in Pembroke is the cold, hard math of property taxes. Newer environmental designations and restrictions have allowed outside groups to receive tax breaks that local elected officials argue are eroding an already precarious tax base.

The loss of Black-owned land in this community exposes a cruel irony. Pembroke has been one of the few places Black landowners could gain a foothold in Illinois, in part because this land was passed over by white settlers who presumed its sandy soils were worthless. And now, after generations without large-scale development or landscape-destroying corporate farming, this land has become sought after by outside conservationists because Pembroke’s savannas remain largely untouched.

Years of protest have done little to dissuade those pushing for more land to be dedicated for conservation.

Local residents have already seen what the future might hold. Most of the sites reserved for conservation ban long-standing local traditions like hunting and picking wild fruit, restrictions designed to remain in place forever, even if the land changes hands. In a community known for Black cowboys, new conservation-minded owners barred horseback riding but, in a couple of instances, protected the right to cross-country ski, not a popular pastime in Pembroke.

Before the arrival of private conservationists, there were no permanent legal restrictions on this land. And, in a place where neighbors knew each other, landowners permitted horseback riders to travel historic trails and passersby to pick wild blackberries regardless of property lines.

The tension has become an ongoing case study in how predominantly white environmental organizations and government agencies — willfully or not — can marginalize communities of color by prioritizing conservation goals over the wishes of residents.

For their part, the conservationists working in Pembroke say they are protecting the area’s most valuable resources and paying taxes on many properties after previous owners had fallen behind and contributed nothing. The Nature Conservancy has stopped buying at tax auctions and says it wants to learn from its experiences in Pembroke. “We understand that for our conservation goals to work in earnest, we need to listen to the residents who know their community best,” the conservancy said in an emailed statement.

But as conservationists and the federal government continue to press on toward their ultimate goal of preserving savannas, some Pembroke residents like Cornell Ward Jr. find themselves on the outside looking in.

One muggy and overcast July afternoon, Ward, a thin-framed 63-year-old man with salt-and-pepper dreadlocks, stood on a gravel road outside Sweet Fern Savanna.

Ward remembers a time when much of Sweet Fern Savanna belonged to Black farmers, including him. Peering beyond the barbed wire fencing and signs threatening to prosecute trespassers, he could see the patch of land where he once grew soybeans. The small patch of land — two adjacent parcels, totaling 3 acres — represented a chance for him to carry on a family legacy that extends back 60 years in Pembroke. Ill and unemployed, Ward lost his properties after he failed to pay $1,511.40 in taxes; they were purchased about a decade ago at county auctions by the preserve’s owner, an 85-year-old conservationist from Chicago’s south suburbs.

“How did they get all of this?” Ward wondered aloud.

Humble Beginnings and Lost Land

No one knows how Joseph “Pap” Tetter escaped the horrors of slavery in North Carolina, only that he, his wife, children and extended family arrived in what would become Pembroke Township in a wagon one day around 1861.

Tetter homesteaded 42 acres of land, which he parceled out and sold to fellow settlers. Proceeds went to help liberate more enslaved people via the underground railroad, according to oral histories.

Unlike the black, spongy soil that made Illinois an agricultural powerhouse, Pembroke’s sandy soil — widely considered some of the poorest in the state — didn’t retain moisture that would allow commodity crops like corn to thrive. But the land offered a fresh start for people who had been owned as property and forced to farm under threat of violence. Through trial and error, they found what could survive the sandy soil, growing specialty crops like okra, collards, peas and watermelons.

“It was available for African American farmers to come in and settle, because it wasn’t being snapped up by European American farmers,” said Mark Bouman, a program director at the Field Museum's Keller Science Action Center in Chicago who has worked with residents, including a local project in conjunction with The Nature Conservancy, and has studied Pembroke’s history. “And so it was kind of like the leftovers.”

Ward’s family moved to the area in the late 1950s after briefly resettling in Chicago following the lynching of 14-year-old Emmett Till in their home state of Mississippi.

Ward’s father, a construction worker, used recycled lumber and materials to build the family’s house on land in northeastern Pembroke, where they raised chickens, goats, pigs and cows. Ward and his 10 brothers and sisters tilled the fields, sowed vegetable seeds and pulled the harvest from the earth by hand.

When Ward’s father died in 1999, he left no will. The siblings couldn’t agree on the fate of the property. Eventually, the family lost the land due to unpaid taxes. On his own, Ward still owned properties elsewhere in Pembroke but then lost those as well. Now some of that land is part of Sweet Fern Savanna.

Farming in Pembroke required long hours in the field, perseverance and faith; the small operations never yielded great wealth. But families carved out a modest living, enjoying the tranquility and spaciousness of the countryside.

Holding on to the land, however, proved tough. Pembroke’s farmers have suffered from the same racial inequities that permeate the American agriculture industry. Without capital or access to loans, they often used outdated equipment or planted by hand. Most farmed their land without irrigation systems, commercial fertilizers and pesticides — the hallmarks of modern agriculture. Many didn’t grow at the scale that would warrant crop insurance, leaving them vulnerable to drought or floods.

As time passed, Black farmers in Pembroke owned less and less land, due in part to financial hardship and lack of access to legal services that complicated the process of bequeathing property to heirs.

Their plight was not unlike that of other Black farmers across the country. In 1920, Black farmers owned about 15 million acres; by 2017, they owned around 4.6 million acres, according to a federal report.

In Illinois, an agricultural behemoth, Black-owned farms collectively make up only 18,659 acres — less than a tenth of a percent of the state’s agricultural lands.

Outsiders Gobble Up Acres

The push to preserve and restore rare natural habitats in Kankakee County, where Pembroke is the largest township by area, might have stalled out two decades ago if the only party interested was the federal government.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service drafted the first plans to create a national wildlife refuge at the Illinois-Indiana border more than 20 years ago, but it was stymied when local residents raised objections and an Indiana congressman blocked federal funding. “We will not establish a national wildlife refuge here until we get funding from Congress, and Congress will not support funding unless the people want it,” Bill Hartwig, then-regional director of the service, told the Chicago Tribune in 1998.

There were no such promises from The Nature Conservancy, which had endorsed the federal plan and accumulated land on the Indiana side of the border. Without any announcement or public input, it began buying on the Illinois side too.

The Arlington, Virginia-based land trust has been praised for its efforts in protecting more than 125 million acres of land globally. But the organization also has been the subject of scrutiny for its real estate dealings.

A 1994 government watchdog report found some environmental land trusts, including The Nature Conservancy, had profited handsomely in some cases from selling land to the federal government. A 2003 Washington Post investigation found the organization had imposed permanent land-use restrictions on some of its properties to guard their natural features, but later sold the land to current and former trustees at reduced prices, some of whom built houses there.

The Nature Conservancy temporarily suspended that program and later announced it would cease selling land to its board members, trustees and employees altogether.

In Kankakee County, The Nature Conservancy started by purchasing 128 acres of forest on the edge of a large commercial farm in Pembroke for $183,000 in 2000. But much of Pembroke consists of tiny, slender tracts of land, meaning the organization had to work on a much smaller scale to expand its footprint.

Some of those tracts became available through public auctions of land lost due to unpaid taxes in Kankakee County. The Nature Conservancy said it has collected 201 deeds at tax sales, totaling 448 acres. It’s not possible to determine the race of all the former owners of the forfeited land, but the population of Pembroke is predominantly Black; local residents and politicians say most of the owners affected by tax sales were Black too.

Because the tax-sale properties tended to be small, those parcels made up less than one-fifth of the conservancy’s acreage in Kankakee County, according to the organization’s own figures. But, among local elected officials, the purchases raised questions about the ethics of buying land forfeited in financially distressed communities.

Those sales, along with the local belief that conservationists were serving as an extension of Fish and Wildlife, fueled a backlash. After an auction in 2015, The Nature Conservancy stopped buying through the tax sales.

That same year, Fish and Wildlife reemerged to reveal it would be pursuing the dormant plans for what it called the Kankakee National Wildlife Refuge and Conservation Area, and the next year it accepted a 66-acre donation to establish the refuge. (The refuge is intended to be primarily in Kankakee County, with a small portion in Iroquois County; the initial donation consisted of land in Iroquois.)

Sharon White, who was Pembroke Township supervisor at the time, joined with other area politicians from the U.S. Congress, the state legislature and local government to push back. The Kankakee County Board voted 22-2 in favor of a resolution objecting to plans for the refuge.

The Nature Conservancy, because of its deep pockets, drew special attention, and White met with conservancy officials.

In November 2016, White placed an advisory referendum on the ballot, asking: “Should The Nature Conservancy be allowed to purchase land within Pembroke Township to establish a conservation marshland?”

Voters left no doubt about their preference, answering “no” by a margin of 708-123. (The Nature Conservancy and its supporters say the vote was misleading because it misstated the type of habitat they are seeking to safeguard in Pembroke; conservationists want to protect savannas.)

“Coming from outside, assumptions were made by the conservation organizations that what they did for the good of the Earth, everybody would automatically love it,” said Bouman, the Field Museum director. “They’ve learned.”

In response to the local outcry, The Nature Conservancy took conciliatory steps, agreeing to temporarily halt land acquisition efforts for eight months. It also agreed to participate in ongoing efforts by the Field Museum and local residents in a Pembroke community planning project.

But conservancy leaders struck a different tone in emails with federal and state government officials. Those emails were obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by ProPublica and examined for this story. Conservancy officials acknowledged the resistance from Pembroke residents and elected officials, but minimized the situation as a “melodrama” in internal documents circulated in a 2016 email.

In an email later that year, Fran Harty, then director of terrestrial conservation at The Nature Conservancy, urged Fish and Wildlife Service officials not to scrap the refuge plans despite community resistance.

“It is important that USFWS does not pull out all together because it will feed the

idea that all you have to do is throw a tantrum and USFWS will pack up and leave,” Harty wrote.

In 2017, Harty speculated how financial hardships for farmers might favor the group’s strategy.

“All it takes is two years of bad corn prices and it changes the chess board,” Harty told a Fish and Wildlife representative.

Officials from The Nature Conservancy’s Illinois chapter, including Harty, who retired in September, declined to be interviewed but provided a statement saying the organization will continue to work with residents of Pembroke toward its conservation goals.

“TNC does not tolerate environmental racism or injustice of any kind as we pursue our land and water conservation work in Illinois and across the world,” the statement said. “TNC’s pursuit of conservation must be inclusive and conducted with humility, trust, and respect.”

White remains skeptical of that commitment, even more so after learning of a 2015 email unearthed by ProPublica.

In 2015, while White was engaged in talks with The Nature Conservancy, she was behind on taxes for some of the parcels she owned in Pembroke. During that time, Harty shared a list of tax-delinquent parcels in Pembroke in an email to a federal official ahead of a county auction, with the note: “Fyi. I will let you know how this works out.” Highlighted in yellow were seven parcels owned by White.

In an interview, White acknowledged she was having trouble keeping up with her taxes due to financial hardship at that time. She paid her taxes, plus interest and late fees, to redeem the deeds before her properties were put up for auction.

In a recent interview, White said she had no idea that her properties, mostly wooded lots neighboring her three-bedroom home, had been discussed by The Nature Conservancy and Fish and Wildlife.

“They knew me and they were trying to buy properties from underneath me,” White said.

A spokesperson for The Nature Conservancy said the organization wasn’t interested in purchasing these parcels, and only highlighted White’s properties “on an information basis to show the areas that were tax delinquent.”

The recipient of the email was John Rogner, who at the time was a Fish and Wildlife Service coordinator. Rogner, now the assistant director of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources, declined to comment about the exchange, saying he did not recall the contents or context of the message.

Regarding the agency’s push for a national wildlife refuge despite the longstanding opposition in Pembroke and elsewhere in the county, the Fish and Wildlife Service said it has sought further public input and will be publishing a final planning report. The agency also emphasized that it will only buy land from willing owners.

“We want to create a sustainable plan for both people and wildlife,” Fish and Wildlife said in a statement. “This is a formative, collaborative process that’s mostly about listening.”

Rogner said that part of the federal process also includes working closely with private conservation groups. That’s what happened in Kankakee County.

“They had already brought under protection significant parcels of land,” Rogner said about The Nature Conservancy, “thus accomplishing some of what the service might have done under the refuge authorization. We coordinated with them in that they shared information about their land conservation so that we could better define what the service role should be.”

Fish and Wildlife also has a relationship with the Friends of the Kankakee, a nonprofit created by Marianne Hahn, the suburban woman who founded the Sweet Fern Savanna.

The group’s stated mission is to support the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Kankakee wildlife refuge. The 66 acres donated by Friends of the Kankakee turned the refuge from an idea to a reality.

A Way of Life Threatened

Pamela Basu, the eldest of the Ward children, is the only one who still owns land in Pembroke and farms there.

As she watches the conservationists buy up parcels and add restrictions, she sees a way of life disappearing.

When Basu was growing up, property lines meant little in a community where neighbors knew each other. Horseback riders followed historic trails. Hunters pursued wild game in the woods.

Basu belongs to a thinning cadre of elders trying to carry on the community’s traditions. She still walks the historic trail on her property, where she collects wild herbs and berries that she uses to concoct sauces, jams and tinctures. Each year, she hosts festivals featuring a farmer’s market, live performances and a nature walk.

“When I was growing up, you could walk from one end of the community to the other with trails,” said Basu. “You can’t walk through the woods anymore. You picked berries, herbs — you knew where things were. We’ve lost that part of our culture, and now you can’t pass that on to other generations.”

Outsiders are increasingly determining the future of the land. Over the years, commercial farmers and real estate speculators have purchased land lost or sold by Pembroke residents. In the past two decades, conservationists also took an interest in the area.

Even though conservationists share a love of the land with the farmers, they often have a very different view of how it should be used.

Among them is Hahn, a retired microbiologist. For years, Hahn volunteered at a nature area near her residence in Homewood, Illinois. But she was vexed by her lack of authority in the preserve. “If somebody wanted to put a trail right through the middle of a prairie, I couldn’t do anything about it. So I thought, why don’t I get my own nature preserve?”

Her larger goal: “My concept of all of this is that, in a small way, I'm saving God's creation.”

A friend and fellow conservationist suggested she make a trip to Pembroke, an area with cheap land and abundant biodiversity. She did and was stunned by the rare prairie plants growing right along the roadside.

She bought 60 acres of land near the center of Pembroke Township two decades ago. This would become the foundation of the township’s first state-designated conservation area: Sweet Fern Savanna.

Creating the nature reserve meant that fields that once produced crops would need to be restored to their previous form. To Hahn, that made perfect sense.

“The parcels aren’t good for farming; people can’t make a living on them. They let them go for taxes — anyone can buy them,” said Hahn, who acquired a small number of the land parcels for Sweet Fern Savanna from auctions. “Should we not buy something that’s being offered to the public at an open auction?”

Over the years, the reserve has more than doubled in size. Signs mark the perimeter, warning, “No Horses. No ATV’s. Violators will be prosecuted.” The site is cordoned off by barbed wire fences, which Hahn said she installed after trash, including roof shingles, was dumped on her property.

Visits to the reserve are allowed only with Hahn’s written permission. For those she lets onto the property, Hahn permits them to hike, birdwatch, cross-country ski, camp and hunt. She said she allows one of her Pembroke neighbors to run his dogs on her property and a friend to hunt wild turkey and deer. Though she has chided trespassing horseback riders, she said, she has never prevented any of her neighbors from picking wild berries there.

Camping and cross-country skiing will no longer be allowed in 2026, according to state records that outline land restrictions for the site. Hahn has also included a special provision to allow a single burial site.

“It was not my intention to create a park. It was my intention to have a nature preserve,” Hahn said.

Hahn’s reserve is one of seven protected areas covering more than 1,100 acres in Pembroke. Five belong to The Nature Conservancy, and, like Hahn, the nonprofit has signed legal agreements with the state imposing some permanent restrictions on these properties in perpetuity with little, if any, public input. These designations are proposed by the landowner, then approved by the Illinois Department of Natural Resources and, in some cases, the governor.

Within the nature preserves created by the conservancy, hiking and sightseeing are allowed. But hunting, fishing, camping, campfires, motorized vehicles and horseback riding are not permitted. The preserves also permanently ban farming, agricultural grazing and time-honored traditions like harvesting wild fruit and plants. (Fish and Wildlife, meanwhile, does allow for wild herbs and fruits to be harvested on the acres it owns, after getting input from the community.)

At Tallmadge Savanna Land and Water Reserve, The Nature Conservancy permits cross-country skiing and deer hunting. But hunting privileges are only granted to those who have completed eight hours of volunteer conservation work.

Local residents wonder why recreation in these natural areas has to be limited.

“I haven’t seen any benefit to the community,” said White, the former township supervisor, who keeps horses in nearby Watseka, Illinois, which is in a different township. “I believe in conservation. There are national parks all over the country where there are hiking paths, horseback riding and camping. So why is it that is restricted to that extent in our community?”

What Is Best for the Local Economy?

The changes brought on by conservationists go beyond how the land is used.

After gaining ownership, conservationists have obtained state designations or imposed land restrictions that drastically reduce what they have to pay in property taxes.

The Nature Conservancy, for example, has enrolled some of its Kankakee County land in the state’s Conservation Stewardship Program, which allows the property to be assessed at 5% of its fair market value. Separately, conservancy land that is earmarked for nature preserves are only assessed at $1 per acre.

As a result, the nonprofit didn’t owe taxes on at least 38 of its parcels in 2020, comprising 382 acres, according to county tax records. That’s because the amounts owed are so small that the county treasurer doesn’t even send out a bill. In some instances, the conservancy pays less than the previous property owners were billed.

In a community where the median household income hovers around $29,000, local residents say it has been difficult to have land seized for failure to pay taxes and then see the new owners get a hefty tax break. In one instance, a Black farmer forfeited a 3-acre parcel of land in 2004 after falling behind on a $580.90 annual tax bill. The Nature Conservancy bought his land at tax sale, and two years later obtained a state conservation designation that allowed the organization to pay $19.60 annually in taxes — 96% less than the yearly amount the farmer lost it for.

But The Nature Conservancy argues that its presence can actually benefit local tax rolls, which can be hurt when landowners fall into delinquency. Organization officials say the group has paid more than $425,000 in county taxes since 2001.

Such arguments, however, have proved unconvincing in Kankakee County. Politicians and residents — Black and white — have strongly opposed conservation-related restrictions and tax breaks.

Antipathy has been especially intense in Hopkins Park because of the village’s desperate need to reverse years of economic stagnation and disinvestment. The conflict pits The Nature Conservancy, which in a 2019 tax filing reported $1.1 billion in revenue, against the mayor of a village that collected less than $37,000 in taxes for that year. Mayor Mark Hodge has led the chorus of naysayers who believe The Nature Conservancy moved too quickly to acquire land, undercutting local development plans along the way.

The conservancy purchased six parcels on Main Street, one of a limited number of places within the township served by water and sewer lines. It also bought land within several residential subdivisions. Though some of these properties were on major township roads, in some cases these areas still had a rural feel, marked by undeveloped land and trees.

“They bought property on our Main and Central streets,” Hodge said. “When they own the property, that means a house can’t go there, a business can’t go there because they are not willing to relinquish it. That would be tax revenue that we would receive for any water, sewer and other utilities. It’s unfortunate.”

He added: “It’s obvious that this is David and Goliath, the big guy trying to crush the small guy.”

The Nature Conservancy said it is unaware of any instances where its landholdings have blocked potential development. Conservancy officials said they considered selling one Main Street parcel to a developer interested in bringing a discount store to the site, but the developer withdrew for unknown reasons.