Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Meanwhile, the bipartisan redistricting commissions some states have set up are turning out to be yet another good political idea that never stood a chance against the prion disease afflicting one side.

Republican House candidates won 53 percent of the statewide vote in 2020 but would hold a projected 65 percent of seats under the new lines, which were approved by the state Senate redistricting committee on Monday. The number of safe GOP seats would double, from 11 to 22, while the number of competitive districts would fall from 12 to just one. Nine Texas House Republicans, including Van Duyne, currently hold seats in districts won by Biden or where Trump won by five points or less, but they’re all drawn into districts that Trump would have carried by double digits. This will push state and national politics even further to the right, as Republicans worry more about primary challengers than Democratic opponents.

Those are the macro atrocities. At the micro level, the size of the Texamander becomes even clearer. Again, from Mother Jones:

Perhaps the most shocking example of gerrymandering occurs in the statehouse map in Bell County, home to Fort Hood, a large military base north of Austin. Republicans split the city of Killeen, which is 40 percent Black, into two bizarrely shaped districts—with one donut-shaped district encircling the other—to protect two white GOP state representatives. “The only motivation for chopping Killeen up is that [if they didn’t], African Americans and Latinos would be able to elect the candidate of their choice,” Texas NAACP President Gary Bledsoe told the Texas Tribune.

(Brief Guy Clark Lyric Interlude: “And she took up with this drummer in some good time Texas scene/And she loved him till the day they shipped him back home to Killeen.” Thank you.)

Elsewhere, the process in Virginia is close to collapse. From the Richmond Times-Dispatch:

On Wednesday, the commission could not agree on what it is trying to accomplish from a political standpoint. It deadlocked on separate 8-8 party-line votes on whether to seek a map with five Democratic-leaning districts, five Republican-leaning districts and one toss-up district, or a map with five Democratic-leaning districts, four GOP-leaning districts and two highly competitive districts.

The deadlock raised the likelihood that the bipartisan commission of eight citizens and eight legislators, established through a constitutional amendment that Virginia’s voters overwhelmingly backed, will fail to agree on maps of the state’s congressional districts or its legislative districts, leaving both tasks to the state Supreme Court.

For some time, “independent bipartisan commissions” were the hot number among solutions to the problem of the ‘Mander. But, since there’s no such thing as a bipartisan anything anywhere anymore, some of them have turned into fool’s gold. Michigan voted in an independent commission a few years back, and civil rights leaders there are up in arms at the new maps that it produced this year. From the Detroit News:

The proposed maps for the state House, state Senate and U.S. House fail to preserve the ability for minority voters to have a voice in government, argued Johnson, who is a member of Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's cabinet. "They dilute minority-majority districts and strip the ability for a minority voter to elect legislative representatives who reflect their community and affect any meaningful opportunity to impact public policy and lawmaking," he said.

Other commentators argued the Michigan Independent Citizen's Redistricting Commission's proposed maps dilute the voting power of Detroiters by putting residents of the overwhelmingly Black city into districts with nearby Oakland and Macomb county suburbs. They urged commissioners to create districts that are majority Black and majority Detroit residents to protect city residents' ability to elect people who represent their needs.

And then, of course, there’s Wisconsin, where everything seems to get both worse and more obvious by the day. From Wisconsin Public Radio:

The People's Maps Commission's proposed district lines would still give an edge to Republicans when it comes to which party controls the Legislature. That's because of Wisconsin's "political geography," where Democrats live more closely together in cities while GOP voters are more spread out.

The commission heard public testimony on redistricting during a series of virtual meetings and took submissions from the public on what the next map should look like. "We trust that our transparent and deliberate process will more clearly reflect the communities where Wisconsinites live, work and vote," said People's Maps Commission chair Christopher Ford.

Republicans had said previously that they won't pass any maps produced by the commission, but Vos indicated in his statement Wednesday that the Legislature "took into account" plans submitted to the panel. Vos also set up his own redistricting portal recently to take similar submissions from the public.

Vos has also indicated that the Legislature intends to pass its redistricting plan before Nov. 11.

The new Wisconsin maps will cement Republican domination of the state legislature for another decade. And this whole thing is headed into the deepest jungles of Depositionland. These commissions are turning out to be yet another good political idea that never stood a chance against the prion disease afflicting one side.

In other news, the latest hot development pandemic-wise seems to be police and firemen leaping in front of TV cameras in order to quit rather than submit to the tyranny of a mandated stronger immune system. This symptom of the pandemic erupted acutely in the state of Washington, where Governor Jay Inslee has been the model of how a governor should act and has been ever since the state got seriously slugged by the first wave of the virus. This has not meant much to the 127 state police officers who were canned this week for being publicly insubordinate, including this guy, who I am happy is no longer carrying a gun in any official capacity. From the Washington Post:

In a parting message broadcast across the agency’s dispatch system, he announced that he was “being asked to leave because I am dirty,” referring to his defiance of the state’s coronavirus vaccine mandate for government employees. The 22-year veteran thanked his colleagues — and offered some choice words for the governor. “This is the last time you’ll hear me in a state patrol car,” said LaMay, 50, who recorded his remarks. “And Jay Inslee can kiss my a--.”

With that, he dropped the radio. Staring into the camera, he said, “That’s it.”

Good for you, pal. I’m happy for the citizens of Washington. And, incidentally, the anti-vax agitation among the country’s police unions is yet another reason why police unions have become such nests for the retrograde that they hardly seem to truly be representing the best interests even of their membership.

And we conclude, as is our custom, in the great state of Oklahoma, whence Blog Official Dust Bowl Bowler of the Year Friedman of the Plains brings us the latest on what the state’s attorney general has been up to recently. From Fox23:

“There are currently no rules that require employers to mandate the COVID-19 vaccine for employees. I urge Oklahoma employers to disregard the Biden Administration’s wishes to the contrary. In the event federal emergency rules are issued that place such an unlawful demand upon employers, our office will be joined by other state Attorneys General across the country to quickly sue and seek an injunction against any implementation or enforcement,” said O’Connor.

O’Connor also said that religious, medical, and personal exemptions could be approved by employers.

“Wishes to the contrary” is a very nice way to hand-wave the Supremacy Clause, AG O’Connor. There will be lawsuits, which this genius likely will lose, and Oklahoma taxpayers will have to pay for them, over and over again.

This is your democracy, America. Cherish it.

Pro-choice protesters march outside the Texas State Capitol in Austin. (photo: Sergio Flores/Getty Images)

Pro-choice protesters march outside the Texas State Capitol in Austin. (photo: Sergio Flores/Getty Images)

Instead, the justices said they will hear arguments next month on whether the Justice Department has standing to sue Texas over a law that denies women the right to choose abortion.

The outcome is mostly a setback for the Biden administration and abortion rights advocates. They had asked the court to block the law as constitutional and procedural issues were weighed.

Instead, the court, over a dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, allowed the law to remain in effect. And the justices said they would weigh only the procedural issues, not the question of whether the Texas law is constitutional.

The Biden administration had argued that Texas was using a private bounty scheme to deny women their constitutional rights.

The Texas Heartbeat Act, known also as Senate Bill 8, authorizes private lawsuits against doctors who perform abortions after a fetal heartbeat can be detected, usually at about six weeks. State and local officials have no role in enforcing the law, but the threat of lawsuits has shut down most abortions in Texas.

It takes the votes of five justices to block or suspend a law, and it appears the court’s conservatives continue to doubt whether abortion rights advocates, including the Justice Department, can challenge a law that relies on future lawsuits by unknown individuals.

This is the second time the court has refused to block the Texas law. On Sept. 1, the conservative majority by a 5-4 vote allowed the Texas law to take effect, saying the case “presents complex and novel ... procedural questions.”

That decision drew sharp reaction because it allowed the nation’s second largest state by population to effectively ban most abortions, even though the Supreme Court has said for nearly 50 years they were constitutionally protected up to about 24 weeks.

A week later, Atty. Gen. Merrick Garland announced the Justice Department was suing Texas for violating the constitutional rights of women there. He won a ruling from a federal judge in Austin, who put the law on hold. But the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals set aside the judge’s ruling by a 2-1 vote in a one-paragraph order.

Responding quickly, the Justice Department filed an emergency appeal on Monday urging the Supreme Court to intervene.

Instead the U.S. attorneys won only a hearing on whether the federal government has standing to sue Texas. The court said it will hear arguments on that issue on Nov. 1.

Dissenting alone on Friday, Sotomayor said the court had been urged again “to enjoin a statute enacted in open disregard of the constitutional rights of women seeking abortion care in Texas. For the second time, the court declines to act immediately to protect these women from grave and irreparable harm,” she wrote in U.S. vs. Texas.

“Texans deserved better than this,” said Amy Hagstrom Miller, founder and chief executive of Whole Woman’s Health, which operates four clinics in Texas.

“We’ve had to turn hundreds of patients away since this ban took effect, and this ruling means we’ll have to keep denying patients the abortion care that they need and deserve.”

The justices are already set to reconsider the right to abortion in a case from Mississippi, which has imposed a 15-week limit on abortions. After winning a review of that issue, that state’s attorneys raised the stakes, arguing the court should overturn the 1973 Roe vs. Wade decision entirely and allow states to make nearly all abortions a crime.

The court will hear arguments on Dec. 1 in that case, Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization.

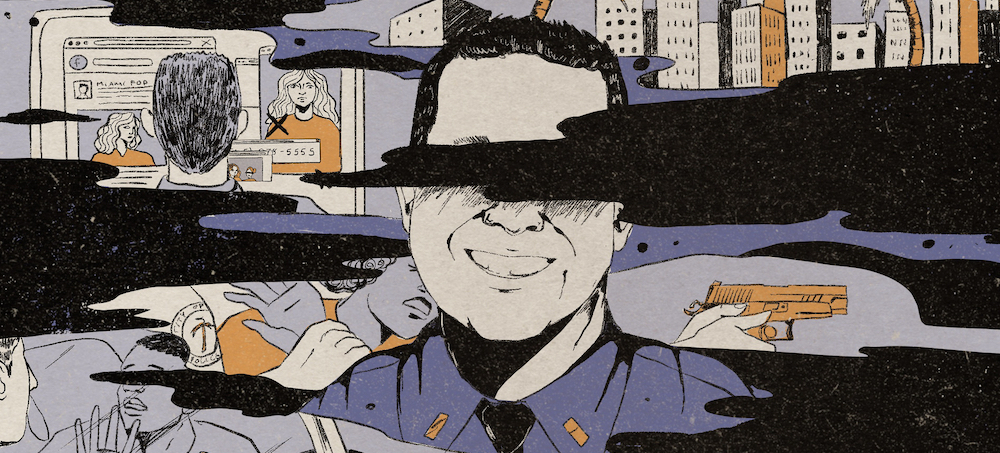

"Captain Javier Ortiz holds a special distinction as Miami's least-fireable man with a badge." (image: Evangeline Gallagher/POLITICO)

"Captain Javier Ortiz holds a special distinction as Miami's least-fireable man with a badge." (image: Evangeline Gallagher/POLITICO)

ALSO SEE: Shane Bauer | How a Deadly Police Force Ruled a City

“This is my neighborhood and I run this shit the way I want to,” police Capt. Javier Ortiz allegedly told a man who wanted to file an Internal Affairs complaint against him.

Over his 17 years on the job — including eight as the union president of the Fraternal Order of Police in South Florida — 49 people have complained about him to Internal Affairs as he amassed 19 official use-of-force incidents, $600,000 in lawsuit settlements and a book’s worth of terrible headlines related to his record and his racially inflammatory social media posts, many of which attacked alleged victims of police violence.

Yet Ortiz has repeatedly beaten back attempts to discipline him. He returned to work in March from a yearlong paid suspension during which state and federal investigators examined whether he “engaged in a pattern of abuse and bias against minorities, particularly African Americans … [and] has been known for cyber-stalking and doxing civilians who question his authority or file complaints against him.” The investigation was launched after three Miami police sergeants accused him of abusing his position and said the department had repeatedly botched investigations into him.

But investigators concluded their hands were tied because 13 of the 19 use-of-force complaints were beyond the five-year statute of limitations, and the others lacked enough hard evidence beyond the assertions of the alleged victims. The findings underscored a truism in many urban police departments: The most troublesome cops are so insulated by protective union contracts and laws passed by politicians who are eager to advertise their law-and-order bona fides that removing them is nearly impossible — even when their own colleagues are witnesses against them.

The story of Ortiz shows the steep public costs of the way elected officials of both parties use the police to keep themselves covered politically: They can demand justice for victims after especially egregious acts of brutality, even while they support contracts and laws that protect officers accused of abuse. They can soothe the victims and at the same time enjoy the benefits of supportive police unions.

Ortiz’s reinstatement in March was no surprise to the many people in Miami who have watched him escape any meaningful punishment for years.

“I’ve known Javi for 15 years. One thing I realized: Wherever he is, you want to be nowhere near him. He’s done nefarious things,” says Miami Police Lt. Jermaine Douglas, who once starred in the true-crime TV series “The First 48,” and more recently accused Ortiz of unfairly disciplining him, a complaint that was upheld by a civilian investigative panel.

“Javi is a bad cop protected by bad leaders,” adds Douglas. “You can say it’s a bad system. The system itself is broken. But at some point, you have managers and leadership above him who are supposed to tame that, to address that.”

But the bosses have claimed there’s little they can do, either.

As a police officer with an encyclopedic knowledge of labor law and grievance procedures, Ortiz shielded himself over the years with the extensive protections woven into the local union’s collective bargaining agreement and Florida’s “Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights,” a police-friendly law that passed decades ago and has been continuously beefed up with bipartisan support. He has also availed himself of a controversial judicial doctrine, called qualified immunity, which shields police from certain forms of liability.

Among the special provisions that have made policing Florida’s police so difficult is a rule in the bill of rights that says all investigations must be wrapped up in 180 days. Critics say the rule is a vehicle for sympathetic colleagues to protect an officer simply by dragging their feet. In its review of Ortiz, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement reported that between 2013 and 2018 seven citizen complaints against him were voided because the department failed to finish investigating within the prescribed time limit.

An even more significant obstacle in the bill of rights is a rule that officers must be shown all evidence against them before they are interviewed about complaints — a right that isn’t afforded to civilians and that flies in the face of normal investigative techniques. It allows officers to tailor their responses to the evidence, avoid being caught in lies and even, says former Miami police chief Art Acevedo, “interfere with the investigation or retaliate” against witnesses.

Upon taking over the department last March, Acevedo reviewed Ortiz’s record and determined that the rules protected him. “Unfortunately — and fortunately for him [Ortiz] — I could take no action,” Acevedo says.

Instead, it was Acevedo, who once received national attention as the Houston police chief when he walked alongside Black Lives Matter protesters, who got fired Oct. 11 by the city manager after a spate of alleged offenses including making an insensitive comment about “Cuban mafia” in heavily Cuban Miami.

Now, the new acting chief, Manny Morales, is telling City Hall insiders that Ortiz has to go — not because of his interactions with the public, but due to his repeated run-ins with other officers on the 1,300-member force.

On Thursday, Morales once again suspended Ortiz with pay — his third time.

But even if Morales decides to fire Ortiz, that might not be the end of the story. A union provision allows officers to ultimately appeal their firings to an outside arbitrator who must be approved jointly by the union and management. Since arbitrators must satisfy management and the union in order to get future appointments, they try hard to show their concern for both sides, overturning a significant percentage of cases, according to critics of the process.

Ortiz has never benefited from this provision directly, but one former chief, Jorge Colina, told POLITICO that the arbitration clause and other cop protections made him “gun shy” about going after Ortiz and others.

Ortiz declined to comment for this story. But one of Ortiz’s lawyers and friends, Rick Diaz, said his client is a man of deep integrity who adheres to an older code of no-nonsense lawmen.

“Ortiz is policing in the past. I think it’s the best way to describe Ortiz,” Diaz says. “He’s policing with an attitude of zero tolerance, strong law-enforcement attitudes in an environment that no longer will tolerate that kind of zero tolerance. And as a result of that, you are butting heads with complaints. You’re butting heads with colleagues. You’re butting heads with supervisors. You’re butting heads with the media. You’re butting heads with judges. You’re butting heads with Internal Affairs.”

While the volume of complaints against Ortiz is large, Diaz emphasized that Ortiz’s official record is clean and he has received just two reprimands for “minor infractions” years ago.

The head of the state’s Fraternal Order of Police, Bobby Jenkins, wouldn’t comment on the specifics of the complaints against Ortiz but said the criticisms about union contracts, the police bill of rights and federal qualified immunity are “incorrect.”

“They fire people all the time. Some get their jobs back. Some don’t. If they didn’t fire him [Ortiz], it means they didn’t have enough to fire him,” Jenkins says. “The reason the police officers’ bill of rights came about was because police officers weren’t given rights like everyone else. You’re entitled to see evidence before you. They can’t lie and tell you it’s there when it’s not there. That’s what it really boils down to.”

But the sheer volume of complaints against the 42-year-old Ortiz tells a different story. Records from the Miami police, Florida Department of Law Enforcement and lawsuits show that those who complained that Ortiz brutalized or harassed them run the gamut: a teacher, a college student, bar patrons, motorists, a maintenance worker installing electrical lines, a drone operator and even two National Football League players arrested at different times in different incidents. In one of Ortiz’s early headline-grabbing cases, he wound up pulling his gun on a trespassing animal rights activist trying to free a pilot whale.

In most cases, people reported being falsely arrested, roughed up or retaliated against for videotaping police or threatening to file complaints. One man reported having his eye socket cracked in a beatdown Ortiz initiated. A woman in another Ortiz arrest said her wrist was broken. Yet another woman claimed she was flung down an escalator outside a bar. Another man reported having nerve loss from overly tight handcuffs.

Throughout, Ortiz never wore or was required to wear a body camera (he agreed to that only this summer), so when citizens complained, it was often their word against Ortiz’s.

Meanwhile, his superiors consistently gave him “satisfactory” job-review ratings in the categories of “use of force” and “contact with the public,” according to employment records.

But Ortiz’s record stands out sharply compared with those of his peers. The 49 citizen complaints against him are 2½ times more than the combined complaints against the department’s four other captains. Those other captains also have a combined 16 use of force incidents on their records, three fewer than the 19 on Ortiz’s record.

Racial issues also stand out. Of the complaints against Ortiz that state and federal investigators reviewed for their civil rights investigation, 39 percent were by Black people and 34 percent by Hispanics, a POLITICO review found.

Ortiz’s controversies aren’t limited to his arrests. As union boss, Ortiz clashed with city commissioners, mayors and even one of his chiefs. He gained national headlines for trying to organize a boycott of a Beyoncé concert for being “anti-police.” Though he previously identified as white and Hispanic, he tussled with a Black city commissioner last year after claiming he was Black. He once organized a protest that ended with angry cops storming City Hall. And he helped push a union lawsuit that led to the weakening of the city’s independent Civilian Investigative Panel, which examines police misconduct.

His willingness to strike back has left Miami politicians reluctant to take him on over the years.

“There’s a distinct hesitancy in Miami to take on the police union, mostly tied to politics and a lack of political will — there’s this fear of the union,” says Melba Pearson, policy director of Florida International University’s Center for the Administration of Justice.

Within both parties, law-and-order politics are still popular in Miami, whose culture of violent crime under the palms has been showcased in TV shows like “Miami Vice,” movies like “Scarface” and the Netflix documentaries “Cocaine Cowboys.”

And the police union is a player in Miami politics.

When POLITICO asked two former Miami city managers, the officials who negotiate the police union contract on behalf of the City Commission, why they didn’t seek tougher terms, they blamed politicians who perpetually fear a police backlash.

“These guys are very well-organized,” says Emilio Gonzalez, who served as Miami city manager from 2018 to 2020. “They’re incredibly smart. They manage their own pension. They know the rules. And the reality is the commission rolls. Politicians don’t want to say no to the FOP. And so the question you have as staff is, ‘How much pain are they going to inflict on me before the inevitable happens anyway?’”

As union president, Ortiz wielded outsize political clout on his own.

City Hall observers say Miami Mayor Francis Suarez made his peace with Ortiz after he was first elected to the office in 2017 and settled a lawsuit filed by the FOP over police wages that had been cut seven years previously during a fiscal emergency. The two men had briefly attended the same high school and more recently have been photographed in chummy grip-and-grin pictures together.

Suarez, a moderate Republican who is trying to turn Miami into a tech hub, said he has had a mixed relationship with Ortiz.

Ortiz backed Suarez’s opponent in his 2009 race for the City Commission and was “very arrogant, very aggressive,” Suarez recalls. “Other times, he acted like he knew you and that you were friends. In Spanish, we would say he displayed a lot of confianza, he would treat you as if you were his close friend when there really wasn’t a relationship there.”

The two later developed a working relationship, Suarez says. He declined to comment on the specific allegations against Ortiz, but quickly added that he’d like to add further accountability measures to the police contract. However, no such language has been introduced into the current negotiations, according to the mayor’s office.

“You don’t want people badgering employees to settle political scores, but we need more ability to have accountability,” Suarez says. “You can have an officer who has racked up 30, 40 or more complaints and maybe none of them is sustained. But should that person be a Miami police officer, or a police officer anywhere? Is that person really in the right place? Is there a mechanism for the city manager to say ‘It’s time to move on, that this isn’t the right profession for you, or for our residents — who are our bosses — if they are constantly complaining about you?’ There’s a disconnect here.”

City Hall watchers and activists are skeptical that Suarez or city commissioners will do anything to bring about change.

“The problem with Francis and these guys saying all this is that they’ve been in office for years — for Francis, it’s 12 years — and what have they done?” says Al Crespo, a longtime activist ran his own news-breaking, and often foul-mouthed, tip sheet, The Crespogram, for a decade. “They talk a good game in the city and throw up this smoke-and-mirrors bullshit, saying ‘Oh, we should do this or that.’ Well, why aren’t you doing it?”

Javier Ortiz was born in 1979 to Cuban-American parents in Miami’s hothouse of anti-communist exile politics, where being tough in defense of one’s beliefs is seen as a virtue and necessity. He attended Christopher Columbus High School, which has traditionally educated the city’s Cuban-American elite, along with its crosstown rival, Belen Jesuit Preparatory School, also a top Roman Catholic academy for boys.

Growing up, classmates recall, Ortiz was more of a victim than a bully.

“He was a very quiet kid, lanky and kind of goofy,” recalls one classmate who graduated with Ortiz in 1997. “He got picked on a lot. It’s an all-boys school and there’s this juvenile testosterone — so kids would flick him in the head or loosen his tie.”

The classmate, who went on to work in the legal profession and encountered Ortiz years later in the course of his work, said he didn’t want to have his name used for fear of retaliation.

“There was this kid I knew who was quiet, almost seemed too sweet, didn’t talk too much, head down,” he said, describing Ortiz. “And then, when I encountered him years later, I was like, ‘Man, this guy?’ I would never have imagined that the Javier Ortiz who was so vulnerable and quiet has turned into this. It’s completely disjointed from the Javier Ortiz that I knew.”

A yen for law enforcement may have transformed him, along with the power that goes with having a badge. Ortiz attended Miami-Dade College and then Florida International University, where he majored in criminal justice and interned with the Miami police, according to Sgt. Stanley Jean-Poix, who quickly became a critic.

“Within a couple days, I thought, ‘This guy is going to be a problem,’” Jean-Poix says now. “He would talk in police code. He would want to pat down guys with me like he was already an officer. Just overzealous and hyper. I thought that whoever picks up this guy is going to have a problem. Guess who picked him up? Miami police.”

Miami police have a long record of citations for excessive force, dating back to the leadership of Chief Walter E. Headley during the civil rights era of the 1960s.

“When the looting starts the shooting starts,” Headley infamously said in 1967, when he promised violent repression in the city’s “Negro areas.” (Headley’s threat was repeated on Twitter by former President Donald Trump in response to last summer’s unrest after George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis cop.) Headley’s legacy also endures through the undying loyalty of the Miami FOP, whose full title is the Walter E. Headley, Jr., Miami Lodge No. 20, Fraternal Order of Police.

Complaints of brutality and unjustified killings of Black people reached a boiling point in the 1980s, leading to violent uprisings in 1982, 1989, 1990 and 1991.

In the midst of it all, the department’s culture of corruption made history with the “Miami River Cops” case that resulted in the firing, demotion or suspension of 100 police officers, including the conviction of 20 officers involved in robbing and murdering drug dealers and distributing cocaine.

While the convulsions of the ’80s were not repeated in subsequent decades, the department’s reputation remained troubled.

After a rash of police shootings — many targeting Black people — Miami voters approved the creation of the Miami Civilian Investigative Panel in 2001.

Then, in 2003, the Department of Justice issued a “technical assistance letter” that “uncovered serious deficiencies in MPD’s investigative practices and observed that officers’ use of deadly force was sometimes avoidable.”

That report came in response to a federal trial that resulted in the conviction of four former Miami officers who planted guns on suspects and lied about four unrelated police shootings that left three unarmed Black men dead and wounded an unarmed homeless white man.

A cop’s cop

Upon joining the force in 2004, Ortiz quickly gained a reputation as an exceptional crime-fighter, catching burglars and stopping drug dealers in troubled neighborhoods, according to his personnel file, which brimmed with commendations for actions such as keeping a woman from committing suicide, helping a stranded motorist late at night and using an electric defibrillator in his squad car to save a heart-attack victim.

Ortiz’s personal charisma and good relationships with colleagues were noted in his early evaluations, with one annual review in September 2006 saying that Ortiz “enjoys interacting with [the] public and doesn't receive complaints.”

It would be the last time that sentiment appeared in his files.

Starting in 2009, Ortiz began racking up complaints from citizens — 15 during that year, a record for him, according to an index of his discipline record, which runs to 13 pages. None of those citizen complaints were addressed in his evaluations covering that year.

Nor did Ortiz’s steadily growing record of complaints raise any concerns the next year. In an annual review in August 2010, a supervisor wrote that Ortiz, then a sergeant, “is extremely courteous when dealing with the public,” eliding any mention of seven more Internal Affairs complaints against Ortiz in the preceding 12-month period.

Those complaints did not include one of his most high-profile confrontations, which happened in January 2009, when he pulled over Jonathan Vilma, a soft-spoken NFL linebacker and local hero who helped win a national title years before at the University of Miami, where he now sits on the board of trustees. An NFL commentator on Fox, Vilma remains widely respected in the community, so much so that Gov. Ron DeSantis invited him last year to speak in favor of a sports bill the Republican signed into law.

Talking publicly for the first time about his arrest at the hands of Ortiz, Vilma said he was horrified when the “crazed” officer pulled him over for reckless driving, pointed a service weapon at his head and then hauled him off to jail. Embarrassing headlines erupted the next day when news of his arrest leaked, but Vilma said he decided not to tell his side of the story because of a media bias in favor of police and against athletes, especially those who are Black.

Like other Black men, Vilma said, he had been given what’s called “the talk” by his dad about how to be overly respectful with officers to avoid any escalation. But it wasn’t enough with Ortiz.

“When I told my dad what happened, he was more upset than I was because every Black male in my family — uncles and my dad — have been arrested for no reason. Every one of them,” says Vilma, who ultimately took a plea deal and paid a fine to avoid a high-profile court case so he could focus on his career.

Eight years after arresting Vilma, Ortiz managed to bust another NFL player. In 2017, Ortiz arrested then-New York Jets wide receiver Robby Anderson at the Rolling Loud hip-hop festival in Miami, claiming Anderson was causing a disturbance, refused to calm down and then shoved Ortiz, who tackled the player and charged him with resisting arrest and obstruction of justice.

The Miami-Dade State Attorney’s Office dropped the charges after Ortiz skipped two depositions and two other officers could not corroborate Ortiz’s account. The Civilian Investigative Panel determined the arrest was improper.

Anderson couldn’t be reached for comment.

Vilma said the arrest is part of a pattern for Ortiz.

“Obviously, no one’s fabricating this,” Vilma says. “How would I make up this crazy story of a cop pulling me over for no reason, pointing a gun to my head and arresting me? I would much rather not have that story. He’s not just bad one time. He’s not just bad a couple times. This is a bad apple, an ugly stain on the police department. And he needs to go.”

In 2009, the year that Ortiz arrested Vilma, Ortiz started to gain real political power when Miami FOP President Armando Aguilar tapped Ortiz to be the union’s vice president.

At the time, the Great Recession was deepening. Tax collections plummeted. Labor costs didn’t. So, in August 2010, the city declared a “financial urgency” under state law and cut city workers’ pay, including that of police. From his union post, Ortiz rose up as the voice of the cop on the street as many officers felt under siege.

The next year, Miami’s Black community was reeling from the police shooting deaths of seven Black men in an eight-month period. Activists and some of the families of the dead men demanded action from city commissioners during a City Hall meeting. Ortiz, in his capacity as union vice president, rose to speak and defended all of the shootings as justified.

The U.S. Department of Justice, however, disagreed.

DOJ launched an investigation into the seven deaths and pointed out that Miami police had shot at people 33 separate times during a three-year period from 2008 to 2011. The Justice Department — noting Miami police were far more likely to shoot people when compared with those in New York — called some of the shootings “unjustified,” rapped the Miami police for poor investigations and record-keeping, and placed the city under federal oversight, which ended only this year.

Throughout, Ortiz’s willingness to stand up for his colleagues was appreciated by much of the rank and file, who admired his confidence and style.

In May 2011, when a Black city commissioner demanded that Ortiz apologize for sending union members a doctored mugshot of a Black man decorated with horns, Ortiz refused to back down.

“This has nothing to do with race. This has to do with the fact that this is somebody that shot at two Miami-Dade police officers,” Ortiz told a local TV station, noting he had “absolutely no regret.”

The blog LEOAffairs, heavily used by anonymous Miami police insiders, lit up with support for Ortiz.

In only three years, he ascended to the union presidency and began winning further plaudits for his aggressive advocacy. Intimidation was part of his game, and politicians were his targets. In 2014, he led a protest of plainclothes officers that resulted in some of them storming City Hall and shutting down a City Commission meeting, demanding better pay and retirement benefits.

In a scene that then-mayor Tomás Regalado now compares with the January 6 riots at the U.S. Capitol, he and most of the city commissioners fled the chamber as the protesting officers, some of them armed, stormed the meeting. The demonstrators then went to the City Hall offices upstairs and began banging on the security glass as staffers hid or fled down a fire escape stairwell, according to then-City Manager Daniel Alfonso.

“It was just surreal,” Alfonso recalls. “There was no one there to call or keep order. I’m trying to tell these guys they’re interrupting the commission meeting.”

“Someone should call the cops,” one woman said, according to Alfonso.

“Ma’am,” he replied, “these are the cops.”

The next day, then-Chief Manuel Orosa condemned the police protesters as a “mob” who intimidated city workers.

Ortiz responded defiantly, saying police were exercising their First Amendment rights and that they wouldn’t be intimidated.

Regalado says the remark was trademark Ortiz.

“If you think about the assault on the U.S. Capitol earlier this year, before that happened, the Miami police stormed City Hall,” says Regalado, a Republican whom Trump appointed to head Radio y Television Marti, a broadcaster directed at Cuba and funded by the U.S. government. “It was crazy.”

While consolidating support among union members at home, Ortiz also cast himself into a national defender of police culture. He took to Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to defend officers accused of brutality in cities across the country.

He helped host a barbecue with police in Ferguson, Missouri, after the department’s shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown led to riots in 2014. The next year, Cleveland police shot a 12-year-old Black child, Tamir Rice, as he played with a toy gun at a park in 2015, but Ortiz called the child a “thug” on his now-deleted Twitter account. (Cleveland just settled the wrongful death case with the boy’s family for $6 million.) In 2016, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, police shot dead a Black man named Alton Sterling at point-blank range as they pinned him to the ground. The killing led to a $4.5 million settlement offer from the city of Baton Rouge this year, but Ortiz at the time wrote that, “many people are afraid to say that the police officers involved in the Stirling [sic] shooting were MORE THAN JUSTIFIED.”

Those comments didn’t sit well with the Miami Community Police Benevolent Association’s members, composed mainly of Black officers and led by Sgt. Jean-Poix, who called Ortiz a “racist” and pointed to his long history of citizens’ complaints.

Down, but by no means out

The crescendo of complaints within the Black community, which were echoed by Black police officers, began to take a toll on Ortiz’s reputation. For years, he had brushed off any criticism with the bravado of a man who operated with impunity.

“I don’t give a fuck. My IA file is as long as this block,” Ortiz allegedly told a bar patron in 2011, according to the man’s Internal Affairs complaint in which he accused the officer of arresting him solely because he was recording another officer aggressively apprehending a suspect.

“I do what the fuck I want to do. This is my neighborhood and I run this shit the way I want to,” Ortiz allegedly told another man who said he would file an Internal Affairs complaint, which he did, in 2009. “Fuck you and Internal Affairs. I will make your life miserable as hell,” Ortiz allegedly said.

The complaints of his own colleagues, however, proved harder to brush off, especially after he gave up his city union perch in 2017. That year, Ortiz became one of the department’s five captains and voluntarily stepped down as president of the Miami lodge, although he continued to serve as the national FOP’s South Florida regional representative.

The accusations of racism — which Ortiz has repeatedly rejected — opened him up to civil rights complaints, meaning that he had to contend with more than Internal Affairs; complainants could reach out to state and federal authorities. Three Miami police sergeants — one of them Black and two Hispanic — did just that in 2018, arguing that Ortiz’s long history of brutalizing civilians, most of them people of color, should cost him his badge.

State and federal officials took the complaints seriously and vowed to investigate. Eventually, the Miami police chief placed Ortiz on paid leave, starting in January 2020.

As the probe dragged on, Ortiz tried to regain his position as union president. He almost did, finishing first among three candidates in the preliminary election. But the fact that he was still on leave pending the results of the civil rights probe helped cost him the runoff this past January to Tommy Reyes, a mild-mannered Trump-supporting Republican.

Robert Buschel, an FOP lawyer who once represented Ortiz, called the investigation into Ortiz “a political hit job. They looked at all these old, unsubstantiated allegations and still found nothing. But they slow-walked it to drag it on as long as possible. This was a systemwide effort — Miami-Dade state attorney, FDLE, FBI — and there was nothing. He got the colonoscopy and the endoscopy at the same time and they couldn’t find anything.”

Indeed, many observers were struck by how little the civil rights probe into Ortiz seemed to matter to some Miami police officers. Lt. Ramon Carr, a member of the Black officers’ association who finished third in the initial FOP presidential balloting behind Ortiz and Reyes, said he was disturbed that many young officers supported Ortiz.

“It shows there’s a culture of people who don’t care about the negativity of what he does, his behaviors, his racist behaviors, his conniving ways,” Carr says. “They didn’t care because they’re like, ‘Well, he’s a good fighter. He will harm himself just to fight for me. And I’ll look past the other stuff.’ What’s that say about us? We should be scared of this. Is this what we’re supposed to be? That’s what’s disappointing about some of the cops in this department who voted for him. If they believe what he believes, then our community is in trouble.”

But Ortiz’s supporters insist he was and is a solid role model.

Al Palacio, an FOP ally of Ortiz’s who is a lieutenant with the Miami-Dade school police, describes Ortiz as a cop’s cop who’s “charismatic, beyond smart [and] a staunch defender of law enforcement. He truly believes in this stuff. He believes in defending those officers who, for one reason or other, can’t defend themselves.”

“He’s unfairly depicted,” Palacio adds. “When you’re an active police officer serving your community in a dense urban area, you’re going to get citizen complaints.”

Palacio says Ortiz stands up for “officers day in and day out wearing bulletproof vests in 95-degree weather trying to stop the wolves from getting to the sheep … Sometimes you feel, especially in the course of the past couple of years, you feel alone. You don’t feel like you have backup.”

He notes that Ortiz, who isn’t married and has no kids, nonetheless helps raise money to fight pediatric cancer.

But one national FOP official, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss Ortiz, offered a different opinion. He said Ortiz went too far too often and, at the very least, became a national PR headache for the union.

“Ortiz is the kind of guy who can get into a fight in an empty room,” the official says. “After a decade, that gets old.”

Seeking to make changes

Ortiz’s return to work in March after the conclusion of the civil rights probe was a personal triumph, proof of his nine-lives endurance, but also a source of anger for the many former superiors who said they wanted to fire him but felt their hands were tied. Alfonso, the former city manager, was one. So was former Miami Police Chief Jorge Colina, who retired in February. Colina had been the chief who ordered Ortiz’s suspension for the duration of the civil rights probe.

Colina says Ortiz was saved by the extremely high bar for firings, enforced by the union-approved outside arbitrator, who has final say over dismissals. Colina says he wasn’t able to take stronger action against Ortiz because he felt the evidence wouldn’t withstand the extreme rigors of the process, and because of Ortiz’s status in the union, which would fight any attempt to crack down on him.

Colina said the arbitrator provision is especially problematic because arbitrators are “chosen in agreement with opposing counsel, and they ultimately want to keep working. So these guys are almost always 50-50 in their rulings: ‘Today, I’ll agree with the city, but tomorrow I’ll agree with the union,’ because if they’re too one-sided, they don’t get hired.”

As an extreme example of the pitfalls of arbitration, Colina points to the time he fired an officer who refused to cooperate in the investigation of a murder in which he might have been involved before joining the force. An arbitrator gave the officer his job back. Colina then fired him again when he refused to take a drug test. The firing stuck.

In another case, two officers accused of falsifying police reports were fired. One arbitrator gave one cop his job back; another arbitrator let the firing against the other officer stand.

“You get a little gun shy,” Colina says of fighting against the union and its shield of contract provisions. “I don’t even call this guy in unless we are rock solid with something, because otherwise we’re just adding to their ability to say, ‘Man, he’s been called in on seven cases that normally you guys wouldn’t have even opened. It’s just that you’re going after him because you’re succumbing to community pressure, political pressure, whatever.’ And meanwhile, of course, that’s not true, but they’re clever in the way that they’ll use the [union] contract for that.”

Also, union leaders can easily argue they’re being attacked because of their role as advocates for fellow officers. Ortiz did just that, for instance, in 2014, when supervisors rapped him for missing depositions in a murder case.

“I am being retaliated against because of my position in the FOP. This is a form of union busting and it effects [sic] my terms and conditions of employment for executing union business,” Ortiz wrote in an evaluation form in 2014.

Ortiz has also been the beneficiary of the police officers’ bill of rights’ “180 Day rule,” which forces Internal Affairs to wrap up investigations within six months. That rule came into play in one of the more high-profile complaints against him, after he launched a social-media attack in 2016 against a woman named Claudia Castillo, who shot video of herself confronting a police officer from another jurisdiction.

Ortiz retaliated by downloading Castillo’s personal Facebook page pictures, posting her cellphone number and pictures, and even tagging local media networks in one post that accused her of drinking alcohol while boating, according to a police investigative report.

Castillo said she was called by strangers and harassed. She filed a restraining order against Ortiz, and he was suspended with pay. (The bill of rights forbids suspensions without pay before an investigation is complete.)

Internal Affairs determined Ortiz broke the department’s rules on proper procedures and courtesy in dealing with the public, but he wasn’t punished because the investigation took more than 180 days. Colina, who was head of Internal Affairs at the time, said he couldn’t remember why the delay happened. (Colina was later accused by a fired cop in a November lawsuit of engaging in a massive cover-up that involved Ortiz, but Colina denies the allegation.)

Castillo suspects her case, too, was part of a cover-up and says she still fears police to this day.

“I’m in fear of a gang. In this case, the gang carries the badges,” she says. “You have no recourse against them. He’s a bully. He’s a cyber bully. He should have been fired for this. He should have been fired for lots of things … He was being the criminal instead of law enforcement.”

In another case, in 2018, Internal Affairs investigators slow-walked a complaint that Ortiz violated departmental guidelines by posting mocking selfies that included Black people being arrested.

As the 180-day clock was about to expire, an anonymous tipster complained to the Civilian Investigative Panel that the department was about to let Ortiz skate free once again, by failing to complete its investigation in time.

Ortiz then showcased his ability to exploit the rules to his advantage. He availed himself of the bill-of-rights provision that allows an officer to review his entire file before offering his response to an allegation. The file Ortiz was given somehow included a copy of the official document that would formally discipline him for violating policy with the mocking selfies, a report on the incident said.

Ortiz knew of another bill-of-rights provision that would block any action until he provided his statement of defense. So outside the sight of the sergeant conducting the investigation, Ortiz signed his own reprimand form. Then Ortiz provided his defense statement. And then he filed a complaint claiming his rights were violated because he was disciplined before he provided a statement and because the 180-day clock had run its course.

The case was dropped. Ortiz wasn’t punished. But the sergeant in charge of the investigation was reprimanded and transferred out of Internal Affairs. He refused to comment. Ortiz’s critics in the department believe he was set up.

Diaz, Ortiz’s lawyer, said he was unfamiliar with the case, but said that he believed “that IA department has been a joke for the past 40 years.”

When it comes to police accountability, reformers say, no provision is as bad as the bill-of-rights rule that lets officers see all the evidence against them before making a statement. It runs contrary to common-sense investigative techniques of police, who routinely withhold information from suspects to see if their story matches up with hard evidence.

Miami lawyer Scott Srebnick says he witnessed the importance of withholding evidence when he managed to catch Ortiz lying about a client named Jesse Campodonico.

Campodonico was beaten and shocked with a taser at Miami’s 2011 Ultra Music Festival by Ortiz and three other officers. Campodonico was charged with battering police officers and resisting arrest, but a bystander’s video showed Campodonico wasn’t the aggressor, contrary to the report filed by Ortiz. Under deposition in the criminal case, Ortiz continued to stick to his official story, unaware of the existence of the video.

“If we don’t have this video, then Ortiz and his cronies would have gotten away with it and kept their story straight,” Srebnick said. “All of the statements in the response to the resistance report were flatly contradicted by the video, flatly contradicted by the video.”

Charges against Compodonico were dropped by the Miami-Dade state attorney’s office, which noted in its close-out memo that Ortiz’s report had “discrepancies” and was “inconsistent” with the video evidence. Srebnick asked prosecutors to charge Ortiz, but the office — which seldom charges police with crimes — declined. A spokesman for the state attorney declined to comment on the case.

Years later, two of the other officers involved in the beatdown of Campodonico, Harold James and Nathaniel Dauphin, were sent to prison after an undercover FBI investigation caught them engaging in extortion.

Campodonico settled a lawsuit against the Ultra Music Festival for $400,000. The next year, Ultra returned to the city but demanded that Ortiz not work security at the event. The city agreed to keep Ortiz away. Ortiz then filed a grievance and sued the city, which eventually prevailed in court, spending staff time and tax money in the process.

In other abuse cases involving Ortiz, the city has dragged out the proceedings by citing the federal doctrine known as “qualified immunity” — which prevents plaintiffs from obtaining judgments against police for anything but deliberate violations of use-of-force guidelines or constitutional protections.

To critics, this federal protection prevents municipalities from bearing the true cost of allowing abusive officers to stay on the force; supporters say it gives police some latitude to do their jobs without fear of lawsuits.

In Ortiz’s case, lawyers claim that qualified immunity saved Miami police hundreds of thousands of dollars in liability. In one case, a motorist named Ruben Sebastian had to fight to obtain a $90,000 settlement after the city tried to scuttle his case by invoking qualified immunity. Sebastian had been pulled over for a minor traffic infraction and wound up getting arrested after Ortiz showed up on the scene. According to Sebastian’s lawsuit, his wrists were so tightly cuffed that it caused nerve damage.

When Ortiz searched his car, Sebastian — who worked as an armed security guard — disclosed he had a firearm. Ortiz then arrested him on a weapons charge, which was later dropped along with all the other charges against him. But Sebastian now has a gun offense on his record and some private security firms won’t hire him, said David Frankel, Sebastian’s lawyer.

“Ortiz cost this man some of his livelihood,” Frankel says.

Frankel said he had to spend extra time fighting the case up to an appeals court because the city invoked qualified immunity, which he said deters many victims of police brutality from even bringing suit.

However, Frankel said the city didn’t fight him as hard in a suit brought by another person complaining of Ortiz’s brutality, a woman named Melissa Lopez. Her wrist was allegedly broken when Ortiz tackled her after she tried to stop him from arresting her boyfriend at a major metropolitan event, Art Basel, in 2017, Frankel said.

The city commission approved her $100,000 settlement in January.

Lopez’s settlement was unusual because of the high bar set by qualified immunity. For instance, Miami attorney Leonard Fenn said he was shocked when an appeals-court judge sided with Ortiz and other officers involved in the violent arrest of his client, a man named Francois Alexandre, when police cleared the streets of revelers in front of his apartment building as they celebrated a Miami Heat basketball title win on June 21, 2013.

Video from a nearby building’s surveillance camera showed Alexandre was backing up from a line of police officers who were advancing as he shot cellphone video. Alexandre stopped briefly when a woman was knocked down in front of him. He backed up an extra step, paused for a moment, and then was head-tackled by Ortiz, followed by a swarm of officers. They broke the orbital bone in his face and he suffered shoulder and wrist injuries, according to a state report of the incident. He was charged with resisting arrest and inciting a riot, charges that were dropped after prosecutors saw the video.

Alexandre sued. The city invoked qualified immunity but the trial judge ruled in Alexandre’s favor. The city then appealed and the higher court ruled in Ortiz’s favor.

“I naively thought that I just had to show the video. This is why I think qualified immunity has to be completely redone,” Fenn said. “Javi’s win is particularly glaring in light of the case law dealing with excessive force … it was really shocking and disappointing to lose on appeal.”

Eight years after he was beaten, Alexandre is still suing, and Fenn said the city “offered a generous settlement, but my guy wants his day in court.”

Seeking change

Civil rights attorney Ben Crump, a Florida-based lawyer who represented the family of George Floyd and a host of other families of Black men killed by police, said the city of Miami’s decision to invoke qualified immunity in Alexandre’s case shows how local officials throughout the country condone police brutality.

“With qualified immunity, there’s little incentive for cities to crack down on this behavior or the police to change their behavior,” Crump says, adding that Ortiz’s story reminds him of the record of Derek Chauvin, the Minneapolis police officer who killed Floyd and had a history of using force against arrestees but was never punished because of state, local and federal protections for police.

“It’s a dysfunctional system,” Crump says.

The city attorney’s office declined to respond.

Crump lent his star power to the push for reforming the qualified-immunity defense as members of Congress sought ways to curb police brutality, a process that is now stalled.

At the state level in Florida, the GOP-led Legislature is increasingly aligned with police unions. The Legislative Black Caucus sponsored a host of police reform bills but none was heard in the 60-day lawmaking session that ended earlier this year. Instead, lawmakers passed a so-called “anti-riot” law expanding police powers and gave first responders an extra $1,000 through the state budget.

“Some want to defund the police, we’re funding the police and then some,” Gov. DeSantis declared at a bill signing.

State Rep. Omari Hardy, a South Florida Democrat, said he wasn’t surprised Republicans refused to hear his legislation, which would have erased the Law Enforcement Officers Bill of Rights and taken investigations of police out of Internal Affairs departments and put them in the hands of civilians. Hardy said Ortiz’s record is a perfect example of how “the status quo is broken.”

“In America, we govern based on the idea of the more power you give someone, the more robust must be your measures of oversight and accountability for this person,” Hardy says. “But with police, we have not only thrown that idea away, we have inverted it. The more power we give police officers, the more loopholes and technicalities they have been given to evade oversight, scrutiny and accountability for abusing that power. That’s what the police bill of rights does. It takes a great American idea and turns it upside down.”

Hardy did notch one victory against Ortiz: After the state representative wrote a letter complaining about Ortiz, the University of Miami barred him for providing security services on campus.

‘Game of Thrones’

When Art Acevedo accepted the job of Miami police chief and spoke to local reporters on March 15, he promised to cleanse the force of violent cops. But he soon realized he couldn’t legally discipline Ortiz for past conduct that had already been investigated.

Nonetheless, he said, Ortiz agreed to wear a body camera and knows he’s being watched.

“You’re not a cat. You don’t have nine lives. You’re out of lives, dude,” Acevedo says he told Ortiz, adding that he believes “lightning doesn’t strike in the same place twice … I’ve never worked in a department with a captain whose name has come up in so many cases.”

Four days after Acevedo made his first Miami appearance, Ortiz drafted a grievance to get his old job back. The previous chief, Colina, had required Ortiz to oversee the department’s motor-vehicle fleet, a demotion compared to his previous job overseeing high-profile units like the bomb squad and SWAT. That grievance is pending.

Former Miami Sgt. Nestor Garcia, one of the three sergeants whose complaints led to the yearlong investigation of Ortiz, says he believes that “Ortiz is untouchable.”

“The problem is he has made political connections through the years. And in Miami, everything is connected,” Garcia says. “There are a lot of backdoor deals, lots of friendships people aren’t aware of where people think others are enemies but secretly they’re friends.”

On that count, Acevedo agrees.

“This place is like ‘Game of Thrones,’” Acevedo says, marveling at the backstabbing and crisscrossing agendas in the police department and City Hall.

Within days of returning to active duty, Ortiz soon became involved in a new spate of controversies and has even taken on the FOP by launching a state-sanctioned process to collect enough votes from officers to form a new union connected to the Police Benevolent Association. He and the FOP’s current president, Reyes, have traded videos swiping at each other.

Reyes told union members that Ortiz “has done nothing in the past three years but been disloyal to our Lodge, bring discredit to our lodge, embarrass us by going and making national news, making memes out of himself.”

Ortiz responded that “I’m far from being a coward.” He said 153 officers have joined his move to leave the FOP because “people want representation. They want professional representation.”

Ortiz also played a role in the firing of two rivals in the department and the demotion of another, who claims the action was racially motivated. The officer later accused Ortiz of retaliatory conduct for scolding and humiliating her.

On May 30, Ortiz was working an extra security detail outside a Miami club and got in a violent altercation with an inebriated man he tased. Ortiz’s police report claimed the man, Juan Castellanos, was also yelling “kill the Jews!” and “white power!” The man’s attorney, Gregory Iamunno, said his client yelled nothing racist and was unfairly targeted by Ortiz.

Two months later, on July 27, Ortiz pulled over a motorist named Stephen Joseph, claiming he was traveling 102 miles an hour on I-95. Joseph, who is Black, refused to immediately give Ortiz his driving information as he asked why he was pulled over, according to an arrest report and a video that Joseph shot of the incident.

Ortiz allegedly dragged him out of the car and forced him down on the hot pavement. A scuffle ensued and Joseph was eventually arrested. Joseph filed a complaint against Ortiz alleging that his money and expensive sunglasses were stolen after his car was impounded, but investigators exonerated Ortiz, saying body camera footage cleared him of wrongdoing. It was the 49th Internal Affairs complaint against Ortiz.

Joseph’s attorney, Jeffrey Chukwuma, said he plans to file a new complaint against Ortiz, accusing him of wrongful arrest and of racially profiling his client.

“He saw a Black man with dreads driving a BMW,” Chuckwuma says. “My client wasn’t speeding. He was driving while Black. It’s part of a pattern with Ortiz if you look over his entire record.”

On Monday, one of the three sergeants who reported Ortiz to state and federal law enforcement, Edwin Gomez, sued Ortiz and the City of Miami in federal court, claiming that Ortiz retaliated against him, creating a hostile work environment and making his life a “living hell.”

Ortiz finally decided to break his silence and give a response to POLITICO, but only about this.

“My official statement — Praying for him,” Ortiz wrote in a text message.

Luke Stewart, a 23-year-old Black man, was asleep in his parked car on March 13, 2017, when he was approached by police officers Matthew Rhodes and Louis Catalani. He was parked legally in Euclid, a suburb of Cleveland, and he wasn't posing a danger to anyone.

Catalani knocked on Luke’s window, startling him awake. They did not announce themselves as officers. Luke sat up and started the car. Catalani and Rhodes immediately opened Luke's car doors and reached inside to forcibly remove him. Catalani grabbed Luke’s arm, and he wrapped his arm around Luke’s head and pulled, while Rhodes pushed from the passenger side.

Scared, Luke attempted to drive away, but Rhodes jumped into the passenger seat. Luke looked at Rhodes and asked, “Why are you in my car?”

Rhodes attacked Luke. He punched him, stunned him with a Taser six times, then used the Taser to strike him in the head. Luke never hit back. Moments later, Rhodes shot Luke five times, killing him. Rhodes had been in the car with Luke for only about one minute before he opened fire.

Luke's killers escape justice

Rhodes had no reason to jump into Luke's car, let alone to use deadly force against him. The 6th Circuit Court of Appeals held that a jury could find that Rhodes’ decision to shoot Luke had violated his constitutional rights. However, even acknowledging this, the court dismissed Luke’s civil rights lawsuit. Why? Because of the hotly debated, court-created doctrine of qualified immunity.

Qualified immunity was meant to protect officers from gray areas and unforeseeable changes in the law: Officers can be held liable only for violations of clearly established laws, and they are protected when they had no advance notice that their conduct would be unconstitutional. The question of what is "clearly established" is constantly in flux but has generally been interpreted in a manner that protects police even when they demonstrate a lack of concern for people’s lives and safety. Unless a court has already found that a highly similar fact pattern violated the Constitution, qualified immunity will protect police from lawsuits and trial.

This defies common sense and undermines constitutional rights for all people. Any reasonable, safe and professional police officer should know the Constitution doesn’t permit police to see a person who isn’t committing a crime, open their car doors, jump into the vehicle, beat them and kill them. But Luke’s case was tossed out of federal court because that same situation had not previously been considered in court – so Luke’s constitutional rights in that situation were not clearly established in the eyes of the court.

In practical terms, that means so long as officers continue to violate people’s rights in unique ways, courts will not hold them responsible.

Mussallina Muhaymin:My brother wanted to go to the bathroom. Police killed him instead.

Federal law allows officers to use deadly force when facing an imminent threat of death or great bodily harm. But qualified immunity shields officers from accountability when they act unreasonably and in violation of the Constitution. Qualified immunity is particularly concerning when used to absolve officers who create dangerous situations and then rely on the danger to justify killing people.

Qualified immunity: perversion of law

Rhodes made the unreasonable, unnecessary and extremely dangerous decision to jump into Luke’s car – and then to remain in that car when he could have left. Luke did not present an emergency or danger to the community, and such drastic action was not necessary.

Rhodes put himself in danger, then he used the danger he created to justify shooting and killing Luke.

Rhodes remains a police officer today. The Euclid Police Department did not discipline him for his actions. And because of qualified immunity, Rhodes has been completely shielded from civil liability under federal law.

The Editorial Board:Hold rogue police accountable: Supreme Court needs to be clear about qualified immunity

The January 6 insurrection. (photo: Getty Images)

The January 6 insurrection. (photo: Getty Images)

Hours after polls closed on Nov. 3, angry Donald Trump supporters on Facebook coalesced around a rallying cry now synonymous with the siege on the U.S. Capitol: "Stop the Steal."

The presidential election may have passed without major incident, but in its wake, "angry vitriol and a slew of conspiracy theories" were fomenting, Facebook staff wrote in an internal report on the Stop the Steal movement earlier this year. Supporters perpetuated the lie that the election had been stolen from then-President Donald Trump — a lie that Trump himself had been stoking for months.

By the time Facebook banned the first Stop the Steal group on Nov. 5 for falsely casting doubt on the legitimacy of the election and calling for violence, the group had already mushroomed to more than 360,000 members. Every hour, tens of thousands of people were joining.

Facebook removed the group from its platform. But that only sent Stop the Steal loyalists to other groups on Facebook filled with misinformation and claims the election was stolen. It was a classic game of whack-a-mole that Facebook tried but failed to stay on top of. Droves of Trump fans and right-wing conspiracists had outwitted the world's largest social network.

In the days after the election, researchers at Facebook later noted, "almost all the fastest growing groups were Stop the Steal" affiliated: groups devoted to spreading falsehoods about the vote. Some even continued to use the name.

They were spreading at a pace that outstripped Facebook's ability to keep up, just as company insiders were feeling relief that election night did not devolve into civil unrest. There was no widespread foreign interference or hacking. These were worst-case scenarios for Facebook. Avoiding them provided solace to the company, even though a pernicious movement was gathering momentum on the platform, something that would only become clear to Facebook after the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection.

The Stop the Steal report was included in disclosures made to the Securities and Exchange Commission by Facebook whistleblower Frances Haugen and provided to Congress in redacted form by Haugen's legal counsel. A consortium of news organizations, including NPR, has reviewed the redacted versions received by Congress. NPR also interviewed experts and ex-Facebook employees to shed light on the thousands of pages of internal research, discussions and other material.

Facebook rolled out "break the glass" measures for the election

As Facebook prepared for the 2020 election, it consulted its emergency playbook. Internally, staffers called these "break the glass measures" — a list of temporary interventions to keep its platform safe.

They included efforts to slow down the growth of political groups that could be vectors for misinformation and extremism. Facebook reduced the visibility of posts and comments deemed likely to incite violence so that people were less likely to see them. And the company designated the U.S. a "high risk location" so it could more aggressively delete harmful posts.

Facebook knew groups dedicated to politics and related issues — which it calls "civic groups" — presented particular risks, especially when it came to amplifying misinformation and growing more quickly than the company could keep up with.

So ahead of the election, the company tried to stop suggesting users join groups it thought they might be interested in; it restricted the number of invitations people could send out each day; in some cases it put group administrators on the hook for making sure posts didn't break the rules, according to an internal spreadsheet describing the measures.

Despite these interventions, Facebook failed to curb the proliferation of the Stop the Steal movement. Inside the company, warnings about how the platform encouraged groups to grow quickly were getting louder. In its internal report, Facebook acknowledged something striking: it "helped incite the Capitol Insurrection" on Jan. 6.

In a statement on Friday, Facebook spokesman Andy Stone rejected the idea that Facebook bore responsibility for the Capitol siege.

"The responsibility for the violence that occurred on January 6 lies with those who attacked our Capitol and those who encouraged them. We took steps to limit content that sought to delegitimize the election, including labeling candidates' posts with the latest vote count after Mr. Trump prematurely declared victory, pausing new political advertising and removing the original #StopTheSteal Group in November," he said. "After the violence at the Capitol erupted and as we saw continued attempts to organize events to dispute the outcome of the presidential election, we removed content with the phrase "stop the steal" under our Coordinating Harm policy and suspended Trump from our platforms."

But what unfolded on the platform and in Washington was especially disheartening to Haugen and other members of the civic integrity team, a group of employees dedicated to tackling political misinformation and protecting elections around the world, which Facebook disbanded in early December.

Haugen and other former employees NPR spoke with say the steps Facebook took around the election and Capitol insurrection show just how much the company knows about the problems endemic to its platform — and how resistant it is to make changes that affect the growth it prizes above all else.

"The thing I think we should be discussing is, what choices did Facebook make to expose the public to greater risk than was necessary?" Haugen said. "We should ask who gets to resolve these tradeoffs between safety and Facebook's profits."

Haugen has filed at least 8 complaints with the SEC alleging that Facebook violated U.S. securities law, including that Facebook allegedly misled investors and the public about its role in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot.

While Facebook "has publicized its work to combat misinformation and violent extremism relating to the 2020 election and insurrection," the Jan. 6 complaint said, the company "knew its algorithms and platforms promoted this type of harmful content, and it failed to deploy internally-recommended or lasting counter-measures."

But the picture that emerges from a review of the internal documents and interviews with former employees is murkier: Facebook did deploy many of its emergency measures. Some didn't work; others were temporary. After the insurrection, as Facebook and the country reeled from images of the besieged Capitol, employees on the company's internal message board blasted leadership for holding back efforts to make the platform safer.

Facebook, in its statement, said it considered "signals" on the platform and worked in collaboration with law enforcement prior to the election and after to decide what emergency steps to take.

"It is wrong to claim that these steps were the reason for January 6th — the measures we did need remained in place well into February," Stone said, adding that some steps, like not recommending political groups, are still in place.

Company researchers highlighted the risks of political groups for months

Inside Facebook, employees had been ringing the alarms for months. In February 2020, staff flagged private political groups as a "high" risk for spreading misinformation during the election.

That's because posts in private groups are viewable only by people who have been invited by a member, or approved by an administrator. Comments, links and photos in these groups operate in something of a Wild West: not subject to Facebook's outside fact-checking program — a core part of the company's approach to keeping lies off its platform. Most political content in groups is seen in these private channels, the employees noted.

Internal research has looked at how Facebook's groups recommendations could quickly send users down partisan political rabbit holes. In a 2019 experiment called "Carol's Journey to QAnon," a Facebook employee created a test user named Carol Smith, a 41-year-old "conservative mom in the US south."

After setting up the account to follow mainstream conservative political news and humor, including pages for Fox News and Donald Trump, the researcher found Facebook's automated recommendations for groups and pages it thought Carol might like "devolved toward polarizing content." Within two days, Facebook served her recommendations for more partisan political groups, such as one called "Lock Hillary Up!!!!" It suggested she follow a page promoting the baseless Qanon conspiracy in under a week.

Company researchers had also warned about how the most problematic groups were fueled by supercharged growth. An August 2020 internal presentation warned that 70% of the 100 most active U.S. civic groups were so rife with hate, bullying, harassment, misinformation and other rule violations that Facebook's systems were not supposed to recommend them to other users.

Facebook removed more posts for violating its hate speech rules in one private Trump-supporting group than any other U.S. group from June to August, the presentation noted. And groups that were punished for breaking the rules found it easy to re-establish themselves; admins regularly set up alternate "recidivist groups" that they encouraged members to join in case Facebook shut them down.

The researchers found many of the most toxic civic groups were "growing really large, really fast," thanks in part to "mass inviters" sending out thousands of messages urging people to join.

So, as the election neared, Facebook put a new "break the glass" measure in place: it allowed group members to invite just 100 people a day. As Stop the Steal flourished after the election, the company dropped that limit to 30.

"The groups were regardless able to grow substantially," the internal Stop the Steal report said. "These invites were dominated by a handful of super-inviters," the report concluded, with 30% of invitations coming from just 0.3% of group members — just as researchers had warned about back in August. Many were admins of other Stop the Steal connected groups, "suggesting cooperation in growing the movement," the report said.

Stop the Steal organizers were also able to elude detection, the internal report said, by carefully choosing their words to evade Facebook's automatic systems that scan content, and by posting to its disappearing "Stories" product, where posts vanish after a day.

While invitation limits were kept in place, other "break the glass" measures were turned off after the election. For example, the company dialed back an emergency fix that made it less likely users would see posts that Facebook's algorithms predicted might break its rules against violence, incitement and hate.

Haugen and other former employees say those election guardrails were taken away too soon. Many on the integrity team lobbied to keep the safeguards in place longer and even adopt some permanently, according to a former employee.

Facebook says it developed and implemented the "break glass" measures to keep potentially harmful content from spreading before it could be reviewed. But it also says those measures are blunt instruments with trade-offs affecting other users and posts that do not break its rules, so they are only suited for emergencies.

One "break the glass" intervention that some members of the integrity team thought should be made permanent slowed down "deep reshares" of political posts. That's Facebook lingo for a post that has been repeatedly shared before appearing in someone's feed — sort of like a game of telephone.