Again a Nightmare Start on Fundraising

“2” donations so far for Friday “2”. Folks there is no way that can work, none, c'est impossible.

Take a moment, give a darn and make a donation you can afford.

Please and thank you.

Marc Ash

Founder, Reader Supported News

If you would prefer to send a check:

Reader Supported News

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

I knew Senate Republicans would refuse to even debate the voting-rights bill, but I had to see this vote to believe it anyway.

But I had to see this vote to believe it anyway. Forget the universal franchise. The Republicans are obviously opposed to universal citizenship. Welcome to 1961, and don’t forget to count the beans in the jar correctly.

And make no mistake, the entire Republican Party is behind the program to restrict the franchise through the vehicle of fanatic conservative majorities in state legislatures, the same fanatic conservative majorities in state legislatures that are calling for these fraudulent “audits” in order to reinforce the Big Lie about the 2020 election. There are no Republican dissenters on this point. Neither Rep. Liz Cheney nor Rep. Adam Kinzinger voted for this bill when it came before the House of Representatives. So they now are investigating the most violent manifestation of the conservative Republican assault on elections—and therefore, on voting rights—and railing against the Big Lie that inspired it, but they voted against any national remedy to the more powerful national movement to make any future “Big Lies” unnecessary. The next time around, nobody will have to break a sweat getting to Washington to break windows and risk jail time. Some state legislatures far from Capitol Hill will take care of the required vandalism—and do it under color of law.

Coincidentally, and coincidence is our only solace these days, a story has emerged thanks to rookie Senator Tommy Tuberville of Alabama. Hard to believe a former football coach would give away this much of the playbook, but Tuberville shared with the Washington Post this amazing tale about the events of January 6. Apparently, while the mob rampaged through the Capitol, and while most of their Republican colleagues were hunkered down in a conference room, Tuberville became part of a rump caucus in a storage closet in which several Republican senators tried to devise a plan by which they could give the mob what it wanted.

Inside the storage closet, a bunker within a bunker, surrounded by stacked furniture, the senators weighed whether the mob’s demonstration of loyalty to Trump that day might affect their own.

“There were 12 of us gathered to talk about what happens now [and] where do things go from here,” said Sen. James Lankford (R-Okla.). The mood was “very heavy,” remembered Sen. Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.). “I do remember saying we have to pull the country together,” said Lankford, “We are so exceptionally divided that it’s spilling into the building.”

Lankford was perfectly willing to consider voting against certifying the results of a free and fair election as long as the subversion of democracy came without a casualty count. What a moderate fellow he is. And, god bless him for being in way over his head, Tuberville added the punchline.

“I didn’t really listen to them,” Tuberville said about the closet colloquy.

(Note: don’t read any further, because the piece goes to great length to explain what a fine fella “Coach” is, and how comfortable he is becoming with being a senator and how much everybody is coming to like him. Alabama traded Doug Jones for this guy. Yeesh.)

On Tuesday night, independent Senator Angus King of Maine took to the floor of the Senate to plead for the voting-rights bill. King, who in the shebeen is known as The Mustache of Righteousness, put the issue into stark relief.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that we are at a hinge of history, that circumstances have thrust us—those of us in this body—into a moment when the fate of the American experiment hangs in the balance. We are the heirs—and trustees—of a tradition that goes back to Jefferson and Lincoln, to Webster, Madison, Margaret Chase Smith, and, yes, our friend John McCain. All were partisans in one way or the other, but all shared an overriding commitment to the idea that animates the American experiment, the idea that our government is of, by, and for the people, all the people. Now is the moment to reach beyond region, beyond party, beyond self, to save and reinvigorate the sputtering flame of that idea.

Yes, democracy is an anomaly in world history and what we have is fragile; it rests upon the Constitution and laws to be sure, but it rests even more so on the trust our people place in our democratic system—and in us.

Listening to King, I thought I was listening to the aging Rep. John Quincy Adams, railing against the “gag rule” that prevented the House of Representatives from hearing petitions that mentioned slavery. Bad things result when legislatures in a republic deem issues too dangerous to talk about.

Make no mistake. There is no point in investigating—or even condemning—the events of January 6, or the Big Lie, if you’re not willing to confront the greater threat to democracy being mounted in dozens of states. This effort inevitably will result in a Trumpian president who will not trip over his own shoelaces. But the Republicans in the Senate, the World’s Greatest Deliberative Body, chose not even to debate the issue. They’re all still in the storage closet, patting each other on the back.

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema. (photo: Getty Images)

Sen. Kyrsten Sinema. (photo: Getty Images)

But how she has handled her growing power in the 50-50 Senate has also cost her something else: support from the left in Arizona, with progressives warning she is now at risk of becoming a political pariah and is potentially vulnerable in a 2024 Democratic primary battle.

"I think the sentiment that I'm hearing out there, voters in Arizona are upset with her, especially Democratic voters," Rep. Ruben Gallego, a fellow Arizona Democrat, told CNN on Wednesday. "I think they support the President's agenda, and they hope that she will, in the end, support the President's agenda, pass reconciliation -- the Build Back Better agenda."

Gallego, who has been frequently mentioned as a potential primary challenger against her in 2024, pointedly did not rule out a run against Sinema.

"For me, all I care about is what happens between now and 2022," Gallego said. "Those questions wait, wait."

The criticism on the left is rampant not only back home but also in the halls of the US Capitol, as Sinema has stood firm against Democratic calls to gut the Senate's filibuster to pass voting rights legislation and joined other moderates in voting against a minimum wage hike earlier this year.

Sinema is not the only Democrat who has infuriated the left. West Virginia Sen. Joe Manchin has refused to go along with many Democratic priorities -- such as generous paid family and medical leave policies, aggressive targets to reduce greenhouse gas emissions --- opening him to constant criticism from liberals in Congress and activists across the country.

Yet Sinema's handling of the situation is markedly different. For months, she has operated in near secrecy, privately holding conversations with the White House about her concerns. She has provided little information to fellow Democrats, other than Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, whereas Manchin has engaged directly with lawmakers and even spent Tuesday at a caucus lunch fielding a barrage of questions and hearing concerns from his Democratic colleagues. Sinema skipped the lunch, meeting with White House officials instead.

"There is a sense in which we no longer live in a democracy; we live under the tyranny of Kyrsten Sinema," said Rep. Ritchie Torres, a progressive New York freshman. "I welcome the ideological diversity of the party. I can live with dissent. My colleagues and I have trouble living with what we perceive to be erraticism. The perception of erraticism is brought on by a lack of communication and clarity for where she stands."

A spokesman for Sinema declined to comment. But aides have noted that she has been clear about her positions with Schumer and Biden since August.

"While we do not negotiate through the press -- because Sen. Sinema respects the integrity of those direct negotiations -- she continues to engage directly in good-faith discussions with both President Biden and Sen. Schumer to find common ground," spokesman John LaBombard said in a statement last month.

What does Sinema want?

Over the past 20 years, the 45-year-old Sinema has transformed from a Green Party, anti-war activist who first ran for office as an independent to a moderate Democratic senator bent on bipartisanship. She now views the late GOP Sen. John McCain, who sparred with his party and reached across the aisle during high-profile debates, as a role model.

As Sinema has emerged as a power player in the divided Senate, she took a McCain-like lead role in cutting a deal on a sweeping infrastructure bill to pump new money into roads, bridges and broadband. The roughly $1 trillion plan won the support of 19 Senate Republicans.

"I don't think we would have gotten that across the finish line without all of her hard work," Sen. Mark Kelly, a freshman Arizona Democrat, said Wednesday. "I think without her it wouldn't have happened, so she deserves a ton of credit for that."

But Sinema has revealed even less publicly during the frenzied debate over the massive social safety net bill, often walking in silence to the nearest elevators when she faces reporters' questions in the Capitol, with her aides saying that she won't negotiate in public. It's that silence that has irked many of her previous allies -- and it even provoked a viral incident where activists followed her into a women's bathroom at Arizona State University.

The entire Democratic agenda now hinges on Sinema since any one defection in the Senate would be enough to torpedo the President's so-called Build Back Better plan. She, along with Manchin, balked at the plan's $3.5 trillion price tag -- the main reason why it was slashed to now near $2 trillion.

According to Democratic sources, Sinema continues to resist higher taxes on corporations and individuals that would raise hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue, raising major questions on how the bill will be fully paid for -- as the White House has repeatedly promised.

"Her position is well known," Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Thursday when asked by CNN if the Arizona senator has conveyed concerns about tax hikes directly to her.

Washington Rep. Pramila Jayapal, a progressive leader in Congress, is at a loss over why Sinema would be opposed to those higher taxes on the wealthy, which would partially reverse the Trump-era cuts Sinema voted against as a member of the House in 2017.

"This is probably the most popular part of the whole package, is the tax pieces of it, and it's hard to understand," said Jayapal, who met with the senator recently but learned little of her policy stances.

"She's really negotiating with the President and, so I feel like what I have is what the President has said to me, which is, she is very much at the table," Jayapal added.

Democratic sources told CNN that Sinema's resistance to a top Biden priority -- tuition-free community college -- was a chief reason why that will almost certainly be dropped from the final package.

Sinema, along with a handful of other Democrats in both chambers, also opposed a provision to allow Medicare to negotiate lower drug prices, a plan fought by the pharmaceutical industry. And Sinema has continued to demand that the House first approve the Senate's $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill, which she helped negotiate and which liberals are holding hostage until they get an agreement on the larger social safety net plan.

Even some Democratic members of her state's delegation take issue with her approach.

"I think she has a responsibility to everyone and the people in Arizona in particular to tell us what it is she thinks she needs to be done," Rep. Raul Grijalva, a progressive from southern Arizona, told CNN on Wednesday. "And while she doesn't make that declaration, I think it puts her in a more and more difficult situation because there's no white or black smoke here. Tell us what you want, and tell us why you want to cut something."

Asked if he believes she could be vulnerable in a primary, Grijalva said: "I think the consequences of what happens in the next few days, is going to make her or not make her vulnerable."

The Democratic congressman added: "If we don't attack issues of inequity, and we don't really deal with climate change, then I think you start talking about reckonings."

Kelly, however, encouraged caution when asked about the criticism she's received from other Arizona Democrats over the massive economic package.

"This thing isn't over yet," the senator said.

Potential primary challenge

The final phases of the negotiations could be critical to her constituents and powerful organizations back home.

In September, AARP Arizona requested a meeting with Sinema after learning that she didn't support allowing Medicare to negotiate lower drug prices. But the senator was unavailable to meet the advocacy group for those over 50 years old, which claims over 900,000 members in Arizona, and instead the organization met with Sinema's staff.

AARP Arizona state director Dana Kennedy said she typically works with the senator's staff, "but [on] something like this, we should hear directly from the senator."

"We do hope she supports allowing Medicare to negotiate because her constituents certainly support it," Kennedy said in an email. "She ran on lowering Rx costs and that is how you do it AND it saves Medicare BILLIONS of dollars."

Sinema's aides though, says they have been public about her stance on the issue and supports other drug pricing proposals, pointing to comments she made recently to the Arizona Republic saying that Congress "should be focused on policies that ensure prescription drugs are available at the lowest possible cost."

Depending on how things turn out, activists say there will be support for a primary challenge in four years.

Marilyn Rodriguez, an Arizona progressive strategist at Creosote Partners, said she has seen polling for Arizona Democratic Reps. Greg Stanton and Ruben Gallego, Tucson Mayor Regina Romero and Arizona Superintendent of Public Instruction Kathy Hoffman showing them to all be credible challengers against Sinema.

"I don't think that we are at the point where Arizona has given up on Kyrsten Sinema," said Rodriguez. "But I do think that we are on the brink."

Nuestro PAC, a Latino mobilization group, has already launched a "Run Ruben Run" campaign, urging Gallego to challenge Sinema in the primary.

"When he gets done running for Congress [in 2022], if he wants to run for the Senate, I'll have a bunch of money to give him and a nice email list," said Nuestro PAC president Chuck Rocha.

Asked if he believes she could lose a primary, Gallego told CNN: "I think there's a lot of time between now and 2024, a lot of time for the senator to put things right with voters in Arizona. And let's hope she does it."

Activists set up a marionette depicting ExxonMobil, Sen. Joe Manchin, President Joe Biden, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, outside the U.S. Capitol on Oct. 20, 2021. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty Images)

Activists set up a marionette depicting ExxonMobil, Sen. Joe Manchin, President Joe Biden, and Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, outside the U.S. Capitol on Oct. 20, 2021. (photo: Tom Williams/Getty Images)

Manchin is knocking down every reconciliation effort to address the climate crisis. Next up is $121 billion is subsidies for fossile fuel companies.

Manchin, whose vote is key to any possibility of passing the already diminished $3.5 trillion reconciliation package into law, said he will not support its most meaningful climate provision. The Clean Electricity Performance Program would have sped up the transition to renewable energy from coal and natural gas by offering power utilities money to make the switch and charging them fines if they failed to do so.

With the cornerstone of President Joe Biden’s climate policy all but dead, Democrats are pushing to get Manchin on board for a suite of tax credits that would incentivize renewables. Manchin has signaled that he’ll only sign on to wind and solar credits if Democrats chip away yet another key provision of Biden’s agenda: the elimination of fossil fuel industry subsidies.

Manchin’s proposed policies would effectively mean that reductions in greenhouse gas emissions won through incentivized renewable production could be canceled out by continued government-incentivized fossil fuel production. The fossil fuel industry subsidies on the table for elimination total $121 billion over the next decade.

“The climate provisions of this package keep on shrinking,” said Lukas Ross, a program manager focused on the federal budget at the environmental advocacy group Friends of the Earth. “If subsidy repeal is no longer part of the discussion, a lot of progressives won’t feel compelled to help carry this over the finish line.”

Progressive Democrats have signaled that the subsidy eliminations remain key. “Repealing these subsidies would finally establish a level playing field for renewable energy and go a long way towards tackling the climate crisis,” Rep. Ro Khanna, D-Calif., told The Intercept. “It’s a top priority.”

Despite Manchin’s cost-conscious approach — he has demanded a reduced $1.5 trillion price tag for the bill — he has fought to preserve domestic fossil fuel industry subsidies. On the potential repeal of international oil and gas subsidies put into place during the Trump administration, Manchin has been silent.

Manchin, who did not respond to a request for comment, has significant personal investments in the coal industry and is also one of the biggest congressional recipients of fossil fuel industry donations, taking in $400,000 between July and October alone, mostly from the oil and gas sectors, according to E&E News.

The subsidies sometimes go to companies that have supported Manchin, like ExxonMobil. Exxon lobbyist Keith McCoy told an undercover reporter for Greenpeace’s Unearthed that the international tax benefits at stake add up to $1 billion for the corporation.

“Joe Manchin,” McCoy responded when asked about crucial members of Congress. “I talk to his office every week. He is a kingmaker on this because he’s a Democrat from West Virginia, which is a very conservative state. He’s not shy about sort of staking his claim early and completely changing the debate.”

It will be up to progressive Democrats’ political calculus to decide whether the fossil fuel industry subsidies survive negotiations. “Clearly everything is at risk,” said Ross. He added, “Clearly progressives have some leverage.”

Building Blocks of a Crisis

The subsidies, which are recorded in law as impenetrable jargon, form the building blocks of a taxpayer-funded system that propels the climate crisis. Analysts have counted well over a dozen fossil fuel industry subsidies, totaling at least $20 billion annually, propping up the U.S. industry.

In his budget proposal, Biden targeted 13 domestic fossil fuel industry subsidies to be slashed, and members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus have fought especially hard for the repeal of four of them.

Among them is a subsidy called the deduction for “intangible drilling costs.” Manchin singled out his desire to preserve the subsidy in a memo to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, which was leaked to Politico.

The subsidy essentially works by allowing oil and gas companies to write off the costs of drilling from their tax bill right away, even before they have produced any oil or gas. If oil prices are high, over the coming decade that subsidy is poised to boost the profitability of new oil and gas fields by 32 and 33 percent, respectively — a bigger impact by far than any of the 15 other major domestic fossil fuel industry subsidies analyzed in a recent study by the Stockholm Environment Institute and Earth Track. If oil prices are low, the subsidy significantly incentivizes new oil and gas drilling that may not happen otherwise.

The subsidy also keeps potential tax money in oil and gas companies’ pockets that could be used to manage the climate crisis. The Biden administration, which supports killing the subsidy, estimated that its repeal would raise $10.4 billion over the next decade.

Another subsidy is known as “percentage depletion” for oil and gas wells. It allows 15 percent of many oil and gas producers’ income to go tax-free. The deduction is meant to account for the cost of developing the well, but the set percentage in many cases exceeds the actual costs.

The deduction is set to boost profitability of new wells by about 3 or 4 percent over the next decade, according to the Stockholm Environment Institute and Earth Track study. If repealed, the Biden administration estimated that it could instead raise $9.1 billion in revenue over that period.

The two subsidies alone, enacted about a century ago, added billions of dollars in value to new oil and gas projects every year, with some years totaling more than $20 billion in added value, according to another study by the Stockholm Environment Institute.

The two other subsidies on the Democrats’ hit list include “last in, first out,” a bookkeeping trick that allows fossil fuel companies to lower their taxable profits, and a loophole that exempts importers and refiners of tar sands oil from paying into the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund used to fund oil spill cleanups. Over the next decade, those subsidies will be worth an estimated $15 billion and $352 million, respectively.

Manchin isn’t the only Democrat who has stood in the way of eliminating fossil fuel industry subsidies. Seven moderate House Democrats signed a letter in September asking that the domestic subsidies be preserved. They appeared to get their way: When the latest version of House Democrats’ reconciliation plan was released in September, the domestic subsidy repeals had disappeared. Progressives are imploring party leadership to help get the repeals put back in the bill.

Trump’s Oil Industry Subsidies

A second set of subsidies that progressives hope to put on the chopping block was born out of President Donald Trump’s 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Republicans addressed American corporations avoiding U.S. taxes on their overseas operations with a new tax, which critics point out allows lower rates for overseas corporate earnings. Fossil fuel firms got an even better deal: The bill’s Republican authors made it so that U.S. oil and gas companies owe no taxes on income from extraction abroad.

The carveout appears to benefit only about a dozen companies, according to a Friends of the Earth analysis, since not many companies drill abroad. The beneficiaries include ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Marathon Oil, Occidental Petroleum, Murphy Oil, EOG Resources, Hess, APA, Kosmos Energy, Talos Energy, and Ovintiv.

Many of the same companies caught a separate tax break on money their foreign subsidiaries earn on transporting, refining, and selling oil and gas. The companies were able to shift those earnings from one tax category to another, significantly slashing the tax rate.

In its 2022 budget proposal, the Biden administration estimated that getting rid of those fossil fuel carveouts could bring in $84.7 billion in revenue over the next decade. The White House estimates that another $1.4 billion could be collected by closing a loophole that allows fossil fuel corporations to claim that royalties and other nontax payments to foreign governments are actually foreign taxes and deduct them from their U.S. tax bill.

The oil and gas industry has fought hard against all the potential changes. ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, and Occidental all noted the 2017 tax cuts in lobbying disclosures for the first half of 2021.

They have allies among Democrats. House members wrote to Democratic leadership twice this fall asking that reforms to international taxes be removed from the reconciliation bill, arguing in part that any changes should be halted while international negotiations over tax policies are underway.

Among the signatories to both letters was Texas Rep. Henry Cuellar, who has been called “Big Oil’s Favorite Democrat” and has received more than $1 million in oil and gas industry campaign donations over his career. Cuellar also signed on to the letter asking that domestic subsidies remain intact.

Ross, of Friends of the Earth, said, “Democrats are advocating to press pause on what could be the only opportunity to do this.”

The stakes are high: “We’re rapidly running out of time to limit long-term warming to 1.5 degrees,” said Ploy Achakulwisut, co-author of the Stockholm Environment Institute reports, referring to the goal agreed upon in the global Paris climate accord. “It just doesn’t make sense at a time when we need to rapidly decarbonize to still be supporting and entrenching the fossil fuel industry.”

This image provided by the Chicago Police Department shows an image from video from a police worn body camera on March 15, 2019, in Chicago. Royal Smart, 8, in blue was handcuffed by police in south Chicago. (photo: AP)

This image provided by the Chicago Police Department shows an image from video from a police worn body camera on March 15, 2019, in Chicago. Royal Smart, 8, in blue was handcuffed by police in south Chicago. (photo: AP)

He was 8 years old.

Neither he nor anyone else at his family's home on Chicago's South Side was arrested on that night two years ago, and police wielding a warrant to look for illegal weapons found none. But even now, in nightmares and in waking moments, he is tormented by visions of officers bursting through houses and tearing rooms apart, ordering people to lie down on the floor.

"I can't go to sleep," he said. "I keep thinking about the police coming."

Children like Royal were not the focus after George Floyd died at the hands of police in 2020, prompting a raging debate on the disproportionate use of force by law enforcement, especially on adults of color. Kids are still an afterthought in reforms championed by lawmakers and pushed by police departments. But in case after case, an Associated Press investigation has found that children as young as 6 have been treated harshly — even brutally — by officers of the law.

They have been handcuffed, felled by stun guns, taken down and pinned to the ground by officers often far larger than they were. Departments nationwide have few or no guardrails to prevent such incidents.

The AP analyzed data on approximately 3,000 instances of police use of force against children under 16 over the past 11 years. The data, provided to the AP by Accountable Now, a project of The Leadership Conference Education Fund aiming to create a comprehensive use-of-force database, includes incidents from 25 police departments in 17 states.

It's a small representation of the 18,000 overall police agencies nationwide and the millions of daily encounters police have with the public.

But the information gleaned is troubling.

Black children made up more than 50% of those who were handled forcibly, though they are only 15% of the U.S. child population. They and other minority kids are often perceived by police as being older than they are. The most common types of force were takedowns, strikes and muscling, followed by firearms pointed at or used on children. Less often, children faced other tactics, like the use of pepper spray or police K-9s.

In Minneapolis, officers pinned children with their bodyweight at least 190 times. In Indianapolis, more than 160 kids were handcuffed; in Wichita, Kansas, police officers drew or used their Tasers on kids at least 45 times. Most children in the dataset are teenagers, but the data included dozens of cases of children ages 10 or younger who were also subject to police force.

Force is occasionally necessary to subdue children, some of whom are accused of serious crimes.

Police reports obtained for a sample of incidents show that some kids who were stunned or restrained were armed; others were undergoing mental health crises and were at risk of harming themselves. Still other reports showed police force escalating after kids fled from police questioning. In St. Petersburg, Florida, for instance, officers chased a Black boy on suspicion of attempted car theft after he pulled the handle of a car door. He was 13 years old and 80 pounds (36 kilograms), and his flight ended with his thigh caught in a police K-9's jaw.

The AP contacted every police department detailed in this story. Some did not respond; others said they could not comment because of pending litigation. Those responding defended the conduct of their officers or noted changes to the departments after the incidents took place.

There are no laws that specifically prohibit police force against children. Some departments have policies that govern how old a child must be to be handcuffed, but very few mention age in their use-of-force policies. While some offer guidance on how to manage juveniles accused of crime or how to handle people in mental distress, the AP could find no policy that addresses these issues together.

That's by design, policing experts said, in part so that officers can make critical decisions in the moment. But that means police don't receive the training they need to deal with kids.

"Adolescents are just so fundamentally different in so many respects, and the techniques that officers are accustomed to using … it just doesn't lend itself to the interaction going well with youth," said Dylan Jackson, a criminologist at Johns Hopkins University, who is working with the Baltimore Police Department on juvenile encounters.

The trauma lasts. Kids can't sleep. They withdraw, act out. Their brains are still developing, and the encounters can have long-term impact, psychologists said.

"I think that when officers understand the basic core components of development and youth development — their social, emotional, physical, psychological development — it can really help them understand why they might need to take a different approach," Jackson said.

Training offered by the National Association of School Resource Officers includes sessions on the adolescent brain to help officers understand why kids react and respond the way they do, executive director Mo Canady said. But not every department makes use of the training.

Canady and other policing experts cautioned against blanket policies that would bar force against younger children.

"You can't say just because a student is 12 that we're not going to use force," Canady said. "Most 12-year-olds you wouldn't. But you don't know the circumstances of everything. You could have a 12-year-old who is bigger, stronger and assaulting a teacher, and you may very well have to use some level of force."

___

Royal, the boy in Chicago, was handcuffed for nearly 30 minutes in the cold, alongside his mother and other adults in the house. Then a police sergeant released him, and an aunt came to look after the children.

Royal's brother Roy, older by one year, stood by watching, not knowing what to say or do. According to a lawsuit filed by the family, police didn't handcuff him because "officers simply ran out of handcuffs." Roy thought his brother was cuffed first because he looked "intimidating": He was wearing a blue hoodie.

That spring, in another pocket of the South Side, Krystal Archie's three children were there when police — on two occasions just 11 weeks apart — kicked open her front door and tore apart the cabinets and dressers searching for drug suspects. She'd never heard of the people they were hunting.

Her oldest child, Savannah, was 14, Telia was 11 and her youngest, Jhaimarion, was 7. They were ordered to get down on the floor. Telia said the scariest moment was seeing an officer press his foot into Savannah's back.

Archie said her children "were told, demanded, to get down on the ground as if they were criminals."

"They were questioned as if they were adults," she said.

Now Savannah's hands shake when she sees a police car coming. "I get stuck. I get scared," she said.

Both families have sued Chicago police, alleging false arrest, wanton conduct and emotional distress. Chicago police did not comment on their specific cases but said revised policies passed in May require extra planning for vulnerable people like children before search warrants are served.

But the attorney for the two families, Al Hofeld Jr., said the incidents are part of a pattern and represent a specific brand of force that falls disproportionately on poor families of color.

"The number of cases that we have is just the tip of the iceberg," he said.

About 165 miles (265 kilometers) due south, in the rural hamlet of Paris, Illinois, 15-year-old Skyler Davis was riding his bike near his house when he ran afoul of a local ordinance that prohibited biking and skateboarding in the business district — a law that was rarely enforced, if ever.

But on that day, according to Skyler's father, Aaron Davis, police officers followed his mentally disabled son in their squad car and chased his bike up over a curb and across the grass.

Officers pursued Skyler into his house and threw him to the floor, handcuffing him and slamming him against a wall, his father said. Davis arrived to see police pulling Skyler — 5 feet (1.5 meters) tall and barely 80 pounds (36 kilograms), with a "pure look of terror" on his face — toward the squad car.

"He's just a happy kid, riding his bike down the road," Davis said, "And 30 to 45 seconds later, you see him basically pedaling for his life."

Video of the pursuit was captured by surveillance cameras outside the police department, and the family has filed a federal lawsuit against the police officers. Two officers received written warnings, according to attorney Jude Redwood. The Paris Police Department declined to comment.

"What they done to him was brutal," Davis said.

___

Kristin Henning, director of the Juvenile Justice Clinic at Georgetown University's law school, has represented children accused of delinquency for more than 20 years and said many encounters escalate "from zero to 100" in seconds — often because police interpret impulsive adolescent behavior as a threat.

"When you are close to the kids, you work with the kids every day, you see that they are just kids, and they're doing what every other kid does," she said. "Talking back, being themselves, experimenting, expressing their discomfort, expressing their displeasure about something — that's what kids do."

Meanwhile, attorneys like Na'Shaun Neal say police who use force on minors often depend on the perception that kids lie. Against an officer's word, Neal said, "no one typically believes the children."

Neal represents two boys — identified as R.R. and P.S. in court papers — who were involved in an altercation with police on July 4, 2019.

It was a few hours before midnight when a San Fernando, California, police officer stopped to ask if they were lighting fireworks, according to a complaint filed in federal court. The boys had been walking through a park, accompanied by an older brother and his dog.

According to the complaint, the officers followed the group and told them it was past curfew; they needed to take the boys into custody.

Police said the boys were responsible for the fracas that followed, and they charged them with assaulting an officer and resisting arrest.

But then a cellphone video, taken by R.R.'s brother Jonathan Valdivia, materialized. And as was the case in the death of Floyd — who was blamed for his own death until a video showed Minneapolis officer Derek Chauvin pinning him to the ground with his knee to Floyd's neck as Floyd cried out for help — Valdivia's video told a very different story.

The video shows an officer forcing his 14-year-old brother to the ground and handcuffing him behind his back. His 13-year-old friend struggles next to him, his neck and shoulders pinned by the officer's knees for 20 seconds.

"Get off of my neck! That's too hard!" the 13-year-old screams.

A judge found the boys not guilty at a bench trial. Neal is suing the city and the police officer on their behalf.

The city of San Fernando has denied that officers used excessive force, maintaining that the boys physically resisted arrest.

"They were very confrontational and aggressive verbally," the city's attorney Dan Alderman said. "Unfortunately, the escalation occurred because of the conduct of the minors, not because of anything the officer did."

___

It is worth noting that R.R. and P.S. are Latinos. Authorities say there are reasons why police officers are more likely to use force against minorities than against white children.

A 2014 study published by the American Psychological Association found that Black boys as young as 10 may not be viewed with the same "childhood innocence" as their white peers and are more likely to be perceived as guilty and face police violence. Other studies have found a similar bias against Black girls.

Tamika Harrell's 13-year-old daughter went to a skating rink with a friend in their mostly white town outside Akron, Ohio, last summer; she was one of only a few Black teens at the crowded, mostly white rink. After a fight broke out, the girl — who was in the bathroom when the brawl began — was grabbed by an officer, roughly handcuffed and thrown into the back of a police car.

Harrell wondered why her kid — the Black kid — was singled out. Before, they had a good relationship with the police. But that's all changed. The incident is still raw. Her daughter won't go out anymore and is having trouble concentrating. The family has filed a lawsuit; the police chief there said he can't comment on pending litigation.

Dr. Richard Dudley, a child psychiatrist in New York, said many officers have implicit bias that would prompt them to see Black children as older, and therefore more threatening, than they are. For instance, police are more likely to think that a Black child's phone is a gun, he said.

It all becomes a vicious cycle, Dudley said. Police react badly to these kids, and to the people they know, so kids react badly to police, leading them to react badly to kids.

Minority children have negative everyday dealings with police and are traumatized by them. "Whatever they've seen police officers do in the past," Dudley said, "all of that is the backdrop for their encounter with a police officer."

So when that encounter occurs, they may be overreactive and hypervigilant, and it may appear that they're not complying with police commands when, really, they're just very scared.

The police are not thinking, "I have this panicked, frightened kid that I need to calm down," Dudley said.

To Dudley and to Jackson, the Johns Hopkins criminologist, de-escalation training for police isn't enough. It must include elements of implicit bias and of mental health, and it must be integrated into an officer's everyday work.

Jackson said he's been working very closely with Black kids in Baltimore, and the first thing he hears often is that they can't go talk to an officer unless that officer is in plainclothes.

"There is a visceral reaction," he said. "And that's trauma. And some of these kids, even if they haven't been stopped over and over again, it's embedded in the fabric of what America has been for a really long time, and they know what that uniform represents in their community."

___

Some of the cases have prompted changes. In the District of Columbia, for example, police officers now do not handcuff children under 13, except when the children are a danger to themselves or others.

The policy was revamped in 2020 after incidents in which two children were arrested: When a 10-year-old was held in a suspected robbery, authorities said that police had correctly followed protocol in handcuffing the child, but then a few weeks later police handcuffed a 9-year-old who had committed no crime.

Age-specific force policies are rare, according to Lisa Thurau, who founded the group Strategies for Youth to train police departments to more safely interact with kids. She said at least 20 states have no policies setting the minimum age of arrest.

Without explicit policies, "the default assumption of an officer is, quite reasonably, that they should treat all youth like adults," Thurau said.

The Cincinnati Police Department also changed its use-of-force policy after an officer zapped an 11-year-old Black girl with a stun gun for shoplifting. The department's policy allowed police to shock kids as young as 7 but changed in 2019 to discourage the use of such weapons on young children.

Attorney Al Gerhardstein, who represented the girl and helped petition for policy change, said the pattern of force he found against kids of color in the city raised alarm bells for him. Records he obtained and shared with the AP show that Cincinnati police used stun guns against 48 kids age 15 or younger from 2013 to 2018. All but two of those children were Black.

But in most departments, there is little discussion around children and policing and few options available to parents aside from a lawsuit. If a settlement is reached, it's often paid by the city instead of by the officers involved.

In Aurora, Colorado, for example, a video of police handcuffing Black children went viral. The video showed the girls, ages 6, 12, 14 and 17, face down in a parking lot. The youngest wore a pink crown and sobbed for her mother. Another begged the police, "Can I hug my sister next to me?"

Police said they couldn't get cuffs on the youngest because her hands were too small.

Their mother, Brittney Gilliam, was taking them to the nail salon. She was stopped by police because they believed she was driving a stolen car. She was not; she had Colorado plates and a blue SUV. The stolen car had Montana plates.

Officials said the officers had made mistakes, but they remained on duty. The officers did not face any criminal charges, and there have been no significant changes to their policies when it comes to children.

The family has since filed a lawsuit.

The family of X'Zane Watts also filed a lawsuit in Charleston, West Virginia, after a 2017 incident that began when police mistakenly suspected the eighth grader of a burglary.

X'Zane said he was playing in an alley near his home with his 2-year-old cousin when three white men in plainclothes got out of their car and started running toward them with weapons drawn, shouting obscenities. They chased him into his house and put a gun to his head, slamming him to the ground.

His mother, Charissa Watts, saw it happen from the kitchen. She didn't know they were police. Neither did X'Zane.

"The wrong flinch, they could have shot him," she said. "The wrong words out of my mouth, they could have shot me."

In the years since, Charleston ushered in a new mayor and a new police chief. They pointed to changes they have made: banning some weapons and chokeholds, requiring body cameras and offering more mental health and de-escalation training.

"Since I became chief of police, we have worked to review policies and provide our officers with the tools they need to keep all our residents and visitors safe — but together we can always do more," Chief Tyke Hunt said.

The Watts family sued, charging that officers profiled X'Zane. They reached a settlement in 2019.

The year after the incident was difficult, X'Zane said. His elbow, injured in the altercation, kept him from playing football; he was angry and distracted. The family moved across town to escape the memories of that day.

Today, X'Zane is doing much better. He hopes to join the U.S. Air Force. And he's been able to put the incident behind him — to a point.

"It has put a longtime fear in me," he said.

The House of Representatives votes to hold Trump ally Steve Bannon in contempt of Congress. (photo: Getty Images)

The House of Representatives votes to hold Trump ally Steve Bannon in contempt of Congress. (photo: Getty Images)

The 229 to 202 vote in the Democratic-controlled chamber was largely along party lines, with nine GOP members joining Democrats. It followed a day of contentious debate, with Democrats and Republicans trading barbs.

Rep. Jim Banks, R-Ind., led the effort for the Republicans, criticizing the probe and its efforts to investigate a private citizen.

"Steve Bannon was a private citizen before, after and during January 6," Banks said. "So why is the select committee interested in Steve Bannon? It's simple. He's a Democrat party boogeyman."

But Banks' statement backed up the crux of the committee's argument, with its lawmakers claiming that as a private citizen, executive privilege does not apply to Bannon.

For his part, Banks was one of five Republicans initially appointed by House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy to serve on the panel, but House Speaker Nancy Pelosi ultimately rejected Banks and Rep. Jim Jordan, R-Ohio. As a result, McCarthy pulled all five, and decided to largely boycott the effort.

That left Pelosi to appoint Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., and Rep. Adam Kinzinger, R-Ill., to the committee.

The two joined the seven Democrats on the committee in defending the effort to pursue a criminal charge against Bannon. And Cheney took aim at her GOP colleagues downplaying the riot.

"There are people in this chamber right now, who were evacuated with me, and with the rest of us on that day during that attack," Cheney said on the House floor ahead of the final vote. "People who now seem to have forgotten the danger of the moment, the assault on our Constitution, the assault on our Congress. People who you will hear argue that there is simply no legislative purpose for this committee, for this investigation or for this subpoena."

Cheney and other members of the panel said Bannon was a key witness, who said on his podcast released Jan. 5 that "all hell" would break loose the next day.

"We will not allow anyone to derail our work because our work is too important," said Rep. Bennie Thompson, D-Miss., chairman of the committee.

What happens next?

Now that House has adopted the contempt report against Bannon, Speaker Nancy Pelosi must certify it to the U.S. Attorney's office for the District of Columbia. The matter could involve the highest levels of the Justice Department, including Attorney General Merrick Garland.

The Justice Department could launch their own investigation, and a grand jury could consider the case as well.

If it reaches an ultimate conviction, Bannon could face fines or jail time.

Bannon's attorney, Robert Costello, had previously pointed to former President Trump's claims that his client was also shielded by executive privilege. However, the panel told Costello that Bannon was not covered by such a legal shield and was in "defiance" of his subpoena.

A Bannon spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for comment on Thursday.

Earlier this week, Trump filed a lawsuit against the panel, challenging its probe.

However, the committee's members have argued that protection rests with President Biden, who waived the privilege regarding an earlier document request. They also argued that Bannon's case especially does not apply since he was a private citizen as of Jan. 6 and not part of the Trump administration.

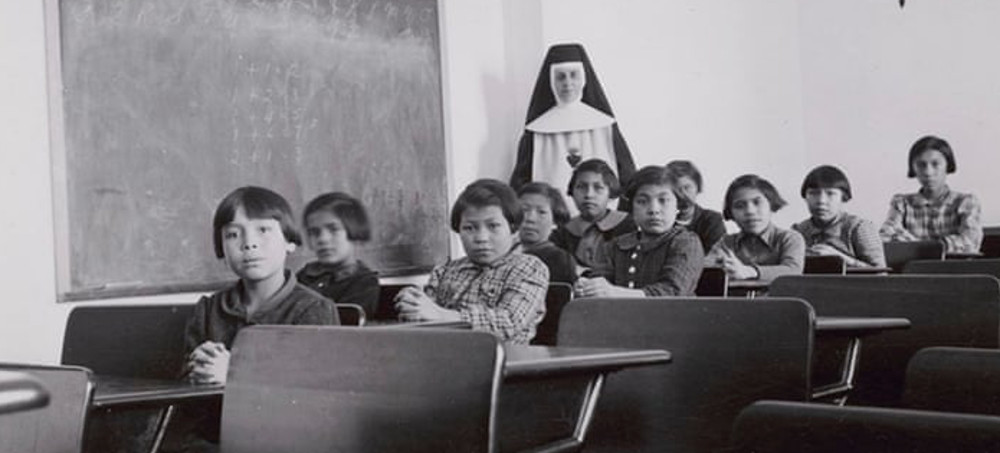

Thousands of mostly indigenous children were separated from their families and forced to attend residential schools between the 19th century and the 1990s. (photo: Reuters)

Thousands of mostly indigenous children were separated from their families and forced to attend residential schools between the 19th century and the 1990s. (photo: Reuters)

In this video, we embedded with a group of archeologists who, using ground-penetrating radar technology, can get a detailed look of disturbances in the ground. They’re looking for shallow pits of about 1 meter in length when looking for the unmarked graves of children.

Their research is helping prove what residential school survivors have long talked about, but were often ignored outside their communities.

Tuskless elephant. (photo: Jacques Le Roux/Getty Images)

Tuskless elephant. (photo: Jacques Le Roux/Getty Images)

But at what cost?

Battling insomnia, Campbell-Staton watched a video about Gorongosa National Park. The park was once Edenic, but during Mozambique’s civil war, from 1977 to 1992, much of its wildlife was exterminated. Government troops and resistance fighters slaughtered 90 percent of Gorongosa’s elephants, selling their ivory to buy arms and supplies. Naturally tuskless females, which are normally rare, were more likely to survive the culls; after the war, their unusual trait was noticeably common.

Campbell-Staton, a biologist at Princeton who studies rapid evolution, had questions. Was this a dramatic example of natural selection in action? Why only the females? Which genes were involved? He idly emailed his questions to a colleague who studies elephants, inadvertently setting off a chain of emails that recast his casual curiosity as serious intent, and soon found himself being introduced to a large group of Gorongosa researchers as “a guy who wants to study the genetic basis of tusklessness in elephants,” he told me. In response to which he thought: Wait a minute, I didn’t say that! I didn’t mean for this to be a whole thing. He had only ever worked with small anole lizards, but even so, when one of those researchers invited him to Gorongosa, he said yes.

Once there, Campbell-Staton met Joyce Poole, a veteran elephant researcher and a co-founder of the conservation nonprofit ElephantVoices. Using historical video footage and modern sighting records, Poole estimated that the proportion of tuskless females had risen from 19 percent before the war to 51 percent after it. The team confirmed that this was an evolutionary response: During the years of intense ivory-poaching, females without tusks were five times more likely to survive than those with them. The elephants then passed on the genes behind that trait to their descendants: About 33 percent of the females born after the war were tuskless.

To identify those genes, Campbell-Staton and his colleague Brian Arnold sequenced the genomes of 18 Gorongosa elephants and looked for stretches of DNA that differed between tusked and tuskless individuals. One region stood out—a small slice of the X chromosome that includes a gene called AMELX. In mammals, this gene influences the production of enamel and the growth of teeth. When it’s disrupted, teeth become abnormal and brittle. It made sense that some fault in AMELX might stop elephants from growing tusks (which, however distinctive, are just very big teeth).

This discovery also explained why only female African elephants are tuskless. AMELX is a bit player rolling with A-listers: Its immediate neighbors include essential genes that animals can’t survive without. But all of these genes are so tightly packed that “it’s hard to mess with one and not the other,” Campbell-Staton told me. A mutation that affects teeth by disabling AMELX could potentially bring down the entire animal if the neighboring genes are affected. Female elephants can tolerate such risk because they have two X chromosomes: If genes are disrupted in one copy, they have a backup. Males have no such luxury: With just one X chromosome, they suffer the full fatal brunt of any change that disrupts AMELX and the genes around it. That’s why tuskless males have never been recorded (at least in Gorongosa). They just don’t survive.

Other genes might also be partly involved in tusklessness, and the team isn’t clear on exactly what changes to AMELX have led to the trait. But evidence from humans suggests that they’re on the right track. In 2009, a team studied an 18-year-old woman who was missing the entire AMELX gene and parts of its essential neighbors. Among several developmental problems, the woman was missing one of her upper lateral incisors, while the other was extremely small. These are the exact same teeth that, in elephants, grow into tusks.

Campbell-Staton’s team has “done a convincing job showing that the Gorongosa elephants have evolved in response to poaching,” Kiyoko Gotanda, an evolutionary biologist at Brock University, told me. Usually, evolution is a slow process, but it can proceed with blinding speed. Hawaiian crickets went from noisy to silent in just 20 generations to avoid a lethal parasitic fly that was eavesdropping on their calls. The anole lizards that Campbell-Staton usually studies ended up with bigger toes and a tighter grip after hurricanes Irma and Maria battered the Caribbean, and better tolerance for cold after a polar vortex hit Texas. But almost all of these examples involved small creatures that breed quickly. To see tusklessness evolving after just 15 years of war, in a “long-lived, slow-reproducing species like the elephant, is incredible,” John Poulsen, a tropical ecologist at Duke University, told me.

Other countries have seen similar patterns. In Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park, the proportion of tuskless females rose from 10 to 38 percent from 1969 to 1989. In South Africa’s Addo National Park, 98 percent of females are now tuskless. These trends suggest that even big, slow-breeding creatures could rapidly adapt to the exceptional pressures exerted by humans, who have been billed as the “greatest evolutionary force” currently operating. But there’s a catch: The elephant’s chromosomal quirk stops males from easily reaching full tusklessness (although their tusks can shrink). And “ironically, fewer tusked females could focus poaching efforts on males even more than it already is, potentially nearly stopping reproduction,” Poulsen said.

Even if the evolution of tusklessness somehow saved elephants from poaching, the loss of their mighty teeth could lead to other losses. Tusks aren’t there just for show. Elephants use them as tools to strip bark from trees and excavate minerals from soil. Rob Pringle, an ecologist at Princeton and one of Campbell-Staton’s colleagues, has shown that these behaviors sculpt the savannah. In damaging trees, elephants create homes for lizards; in toppling other trees, they open up spaces for understory plants. A population of tuskless elephants is better than having no elephants at all, but it’s not functionally the same as a population of tusked ones. They’d be changed, and so probably would the world around them, and “all because we want their teeth, which sounds just absurd when you say it,” Campbell-Staton told me.

He and his team are now planning to study the consequences of tusklessness—and whether its rise has changed the elephants’ diet, the way they move nutrients across the land, and the other plants and animals in their environment. In doing so, they hope to complete the full story of Gorongosa’s tuskless elephants—a tale in which the economic forces that dictate the price of ivory and the political history that drives a country to war collide upon a handful of genes in a single charismatic species, in a way that could reshape an entire ecosystem in the space of a few decades.

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment