Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

Why has the effective end of Roe v Wade been met with shock by so many corners of political life?

Perhaps the form of Roe’s eventual downfall was a surprise. Few thought that Roe’s fatal case would be over Texas’s new abortion law, with its privatized enforcement system of bounty-hunting civil suits designed to elide judicial review. And among a sea of legal observers, only Cardozo law professor Kate Shaw seems to have predicted that the court would dispose of a long-established constitutional right in so rushed and perfunctory a proceeding as a late-night order on the shadow docket. But this outcome was never in doubt. Trump promised to appoint antichoice judges. He kept that promise. This week his three appointees – Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett, joined by Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas – did what all of them know they were put on the court to do. They allowed the first state to outlaw abortion within its borders.

So why has the effective end of Roe v Wade, coming in a one paragraph order in the wee hours of Thursday morning, been met with shock by so many corners of political life? The Republican party’s control of the federal judiciary had left little doubt that those judges most inclined to strip women of their rights would have both the power and the opportunity to do so. And yet politicians, pundits, and legal observers had for years assured the public that the justices would not gut abortion rights, despite the clear evidence that they would. We were assured that the Republicans on the court were less determined to gut Roe than they appeared to be, and that those worried about the future of abortion rights were overreacting.

The court would not gut Roe, we were told by politicians and academics, because they said they wouldn’t. Kavanaugh, the ruddy-faced Trump appointee, had referred to Roe as “important precedent”. That this rather tepid comment was a disingenuous bit of posturing meant to ease his confirmation to the court was evident to everyone. Nevertheless, defenders of the confirmation process implored the public to treat it as if it had been uttered in good faith.

In a speech announcing her decision to vote to confirm Kavanaugh, Senator Susan Collins said that she believed Kavanaugh would not vote to overturn Roe, or to gut it procedurally, because “his views on honoring precedent would preclude attempts to do by stealth that which one has committed not to do overtly.” Of course, the court, with Kavanaugh’s help, did effectively overturn Roe “by stealth” – in an unsigned order in the middle of the night.

Of the feminists who opposed his nomination, Collins was dismissive, even patronizing. “We have seen special-interest groups whip their followers into a frenzy by spreading misrepresentations and outright falsehoods about Judge Kavanaugh’s judicial record.” She condemned these women’s concerns as “over-the-top rhetoric and distortions”.

The court would not gut Roe, we were told by the legal world, because the justices were too professional. Barrett, the third of Trump’s appointees, had been a member of an antichoice faculty group while a law professor at Notre Dame. She had given a lecture to a Right to Life group; she had signed a letter condemning Roe and its “brutal legacy”. And yet despite Barrett’s extremist and evidently very passionately held views on abortion, people posing as serious told us that we could not know how she would vote on abortion rights, that the opinions and worldviews of judges would somehow not affect their legal judgement. “My personal views don’t have anything to do with the way I would decide cases,” Barrett told Senator Patrick Leahy when she was asked about her lengthy history of anti-abortion advocacy. The statement insulted both Leahy’s intelligence, and ours.

And yet as conservative, antichoice judges consolidated their power, several myths about the court persisted. We were told that the people who looked like rabidly conservative justices were really reasoned moderates; or that at least they would be professional and impartial in their judgements; or that at least the removal of abortion rights would move slowly. These myths were presented as the only serious way to understand the court. Feminist claims that what appeared to be happening really was happening – that the judiciary really had been taken over by antichoice zealots, that the ability of women to control their own bodies and lives would soon be stripped away – were labeled as delusional and silly. Faith in the integrity of the conservative justices was cast as informed, mature, and intelligent. And it was contrasted with the supposed hysteria of feminists, whose passion and fear was taken as a sign of their own delusion, not as an indication of the seriousness of the problem.

This notion, that the only intelligent response to a threat to women’s rights is to be calm, blasé, and preemptively assured that nothing very bad or important will result, has been weaponized with particular insidiousness over the course of the abortion debate during the past five years. In the halls of power, contempt for abortion rights activists was nearly complete.

After Kennedy’s resignation, the CNN host Brian Stelter took to social media to scold a liberal activist for her fear of a Roe reversal. “We are not ‘a few steps away from the Handmaid’s Tale’,” he wrote. “I don’t think this kind of fear-mongering helps anybody.” Confronted with women opposed to the confirmation of Kavanaugh, Senator Ben Sasse all but rolled his eyes. There had been, he said, “screaming protesters saying ‘women are going to die’ at every hearing for decades.”

The insistence that Roe is not in danger, and that women’s fear is silly, persists even now, after the court has effectively ended Roe. “Now breathe,” wrote the law professor Jonathan Turley in a blogpost urging women’s rights advocates to calm down, as if they were toddlers in the midst of a temper tantrum. “It is ridiculous to say that it was some manufactured excuse for a partisan ruling.”

Is it ridiculous? The public has no real reason to believe that the supreme court is acting in good faith – aside from the repeated assurances of supposed experts whose predictions have usually been wrong. Instead, it was the so-called alarmist feminists, the ones warning about manufactured excuses for partisan attacks on abortion rights, who got their predictions mostly right. Maybe these women are not so ridiculous after all. Maybe it’s time to start listening to them.

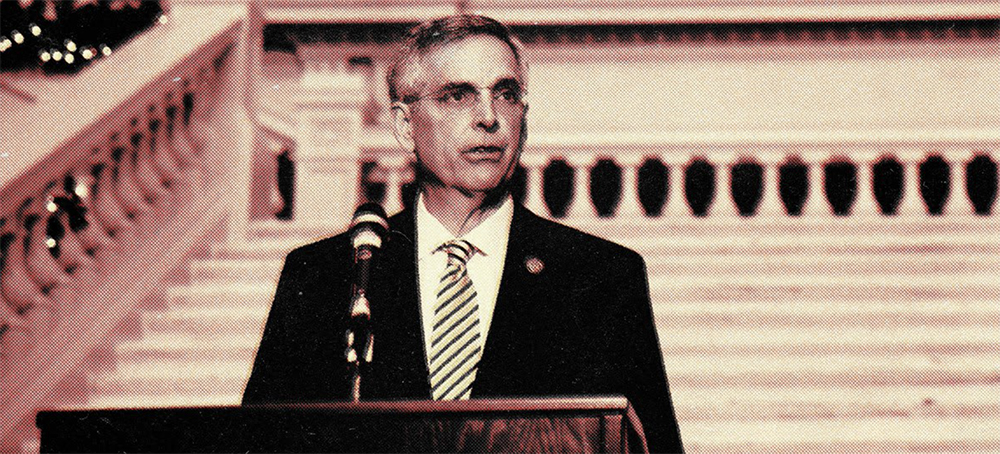

Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Getty Images)

Georgia secretary of state Brad Raffensperger. (photo: Elizabeth Brockway/The Daily Beast/Getty Images)

In the years since leaving the military, retired Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal has been a board member or adviser for at least 10 companies while running a boutique consulting firm and teaching at Yale University. (photo: Melina Mara/WP)

In the years since leaving the military, retired Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal has been a board member or adviser for at least 10 companies while running a boutique consulting firm and teaching at Yale University. (photo: Melina Mara/WP)

Stanley A. McChrystal exemplifies how ex-generals sell their battlefield experience in other arenas, from corporations to covid-19 response.

McChrystal recalls that question in his 2015 management manual, “Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World,” which says his wartime leadership techniques can guide organizations far from the battlefield toward “successful mission completion.”

The failure of the American mission in Afghanistan became deadly apparent last month when the Afghan army collapsed as the Taliban took control.

But the generals who led the mission — including McChrystal, who sought and supervised the 2009 American troop surge — have thrived in the private sector since leaving the war. They have amassed influence within businesses, at universities and in think tanks, in some cases selling their experience in a conflict that killed an estimated 176,000 people, cost the United States more than $2 trillion and concluded with the restoration of Taliban rule.

The eight generals who commanded American forces in Afghanistan between 2008 and 2018 have gone on to serve on more than 20 corporate boards, according to a review of company disclosures and other releases.

Last year, retired Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr., who commanded American forces in Afghanistan in 2013 and 2014, joined the board of Lockheed Martin, the Pentagon’s biggest defense contractor. Retired Gen. John R. Allen, who preceded him in Afghanistan, is president of the Brookings Institution, which has received as much as $1.5 million over the last three years from Northrop Grumman, another defense giant. David H. Petraeus, who preceded Allen and later pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor charge for providing classified materials to a former mistress and biographer, is a partner at KKR, a private equity firm, and director of its Global Institute.

Petraeus said several firms “aggressively sought” him for his military and CIA experience. As for his leadership in Afghanistan, he said, “I stand by what we did and how I reported it during my time.” Dunford said he pushed no policy in Afghanistan but “did exactly what the president directed me to do,” and that 80 percent of his time now is devoted to nonprofits, several serving veterans. Allen, through a spokeswoman, declined to comment.

McChrystal is the runaway corporate leader. A board member or adviser for at least 10 companies since 2010, according to corporate filings and news releases, he also leverages his experience to secure lucrative consulting contracts on topics distant from defense work, such as managing the coronavirus pandemic for state and local governments. The general, who was dismissed after being quoted in 2010 disparaging then-Vice President Joe Biden, has made millions from corporations, governments and universities, commanding six-figure salaries for some of his board positions and high five-figure speaking fees.

For a position on JetBlue’s board between 2010 and 2019, he was paid a total of more than $1.3 million, disclosures show. He made roughly the same amount between 2011 and 2018 from Navistar International, a vehicle and engine manufacturer. One of its subsidiaries agreed this spring to pay $50 million to resolve claims it defrauded the U.S. Marine Corps more than a decade ago by inflating the prices of armored vehicles used in Afghanistan and Iraq. McChrystal said he had been unaware of the dispute, which did not involve allegations of wrongdoing on his part. Navistar denied the allegations and admitted no wrongdoing in the settlement.

Corporations seek out ex-military officials because they’re thought to hew to ethical codes and conduct themselves well in crisis, said Megan Rainville, a specialist in corporate finance and governance at Missouri State University. At the same time, her research has found that companies advised by board members with military experience are less likely to invest in research and development and have lower value than firms whose board members lack such experience, said Rainville, a former defense industry financial analyst.

“Team of Teams,” drawn from McChrystal’s experience helping large organizations function more like small teams, presents the pitch his consulting firm, McChrystal Group, makes to clients as disparate as ExxonMobil and public health agencies confronting covid-19. The book also contains the lessons he delivers to students at Yale University. The retired general teaches a course called simply, “Leadership.”

Now that the war’s failures have been laid bare, the leadership capabilities of those who perpetuated it should be reevaluated, said Daniel L. Davis, a retired Army lieutenant colonel who served two tours in Afghanistan. Military strategies used in Afghanistan will not aid U.S. businesses or governments, he argued.

“For years it’s been payday for the generals while the war itself has been a complete disaster,” said Davis, a senior fellow at Defense Priorities, a think tank urging military restraint. “At what point do we hold anyone accountable?”

McChrystal, 67, rejected that view, saying in a more than hour-long video interview with The Washington Post that he stood by his military decisions as well as his post-military earnings.

“I have built a business which has given a place for some of my old comrades to work and for a bunch of young people to have a special experience,” he said.

The retired general, whose father served in Germany during the American occupation after World War II, said his personal measure is whether there’s anything about his career that would disappoint his wife or, one day, his grandchildren. “And there’s not,” he said.

McChrystal, who endorsed Biden last fall, said it was too soon to draw conclusions about the president’s move to end the war. He allowed that the 20-year conflict “has had a very disappointing outcome,” but said, “I don’t think that means that necessarily many of the decisions made and the strategies pursued were wrong. I think in many cases they were the best strategy that could have been.”

Senior military leaders who choose to sit on corporate boards or run businesses — after commanding “thousands and thousands of people” — are acting appropriately, he said.

“It’s not a bunch of people getting their snout in the trough and just trying to get rich,” McChrystal said. “If you’ve risen to that level, you develop that skill level, that’s what the opportunities that come are. And I don’t think that’s wrong.”

‘The good guys in the equation’

The University of Nebraska at Lincoln was facing the prospect of curtailing research programs because of budgetary pressure in 2013 when it invited McChrystal to campus. For a keynote address at the university’s “Building the 22nd Century” conference, the university proposed what it understood to be his standard speaking fee: $62,500.

There was a hitch. Because of a board meeting in Chicago earlier that day, McChrystal required a private jet, a representative from the general’s speakers bureau, Leading Authorities, told university officials in emails obtained as part of a public records request. The fee would have to be higher: $80,000.

The university agreed, ultimately paying only $70,000, the emails show, because he made do without the jet. Asked about the fee, McChrystal said it sounded high but declined an invitation to review the contract, noting that he gives some speeches pro bono but has less control when his speakers bureau is involved.

McChrystal’s value to the university, the emails specify, came from his “efforts in leadership, statesmanship, innovation, change management, and international affairs.”

He brings the same insights to the boardroom, according to business executives close to the 1976 U.S. Military Academy graduate who rose through the ranks while winning academic fellowships and gaining a reputation as an ascetic, eating just one meal a day. After earning plaudits for reforming the elite counterterrorism unit known as the Joint Special Operations Command, and then directing the Pentagon’s Joint Staff, he took command in Afghanistan in 2009.

But one year later, he was ousted over a bombshell Rolling Stone profile depicting him as a “runaway general” who condoned contempt for civilian leaders. He apologized at the time for his “poor judgment” and told The Post in a 2015 interview that the episode taught him to prepare for the unexpected and not put too much stock in the judgments of others.

Despite the scandal, he remained in the business world’s favor partly because of then-President Barack Obama’s decision to let him retire with four stars, said former military colleagues — a move that also left him with an annual, taxpayer-funded pension of at least $149,700, according to Pentagon estimates at the time.

At Deutsche Bank, he has conducted leadership training, according to two former executives, leading to a seat on the board of the bank’s U.S. holding company. “Senior management is much more likely to listen to military commanders because they’re cool and they’ve killed people than to a McKinsey guy in a pinstripe suit,” said a former senior Deutsche Bank executive who, like some others, spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss human resources issues. A Deutsche Bank spokesman declined to comment.

A former vice president at Knowledge International, an Alexandria-based affiliate of an Abu Dhabi company that says it “exports close to $500 million annually in defense services and products,” mostly to the United Arab Emirates, said McChrystal was “valued for his name and gravitas that he brought to the board.”

McChrystal said he joined the board of Knowledge International, which did not respond to a request for comment, because a former boss, retired Gen. Bryan D. “Doug” Brown, asked him to. In an interview, Brown said the board members, by handling the authorizations for overseas defense work, were “the good guys in the equation — making sure everyone is moral, legal and ethical going over there.” He called McChrystal “one of the finest officers and people I’ve ever known.”

McChrystal’s obligation in Chicago that led his speakers bureau to request a private jet was a meeting of the board of Navistar International, the manufacturer based in Lisle, Ill., he said. When McChrystal was named to the board in 2011, Navistar’s chairman said, “His years of military leadership and service will be of great value to Navistar as we further expand our global and military businesses.”

While commercial vehicles represent the heart of Navistar’s business, McChrystal said, the company began making mine-resistant vehicles, known as MRAPs, “during the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, when suddenly there was this need.” Its traditional trucking sales began contracting in 2005, he said, but revenue from the military-grade equipment “hid that problem” during the height of the two wars.

In 2013, a Navistar contract director filed a whistleblower complaint alleging the company had forged invoices and pricing information for MRAPs sold to the U.S. government between 2007 and 2012. McChrystal, who joined the board in 2011, was on its finance committee at the time of the complaint, and earned about $200,000 annually, corporate filings show.

The U.S. intervened in the whistleblower suit in 2019, arguing in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia that the fraudulent documents had duped the government and cost it at least $1.28 billion.

The matter had come into public view before then. In 2016, Navistar divulged in an annual report that it had received a subpoena from the Pentagon’s inspector general related to its sales of military vehicles to the government. The company did not respond to a question about what it told the board about the underlying complaint, pointing instead to public filings that spell out the board’s responsibilities. McChrystal, who left the board in 2018, said he was unaware of the claims until this spring, when he read about the settlement in the news.

An attorney for the whistleblower, H. Vincent McKnight Jr., said he remains troubled by what he sees as ill-gotten gains, especially because the scheme exploited the American military and taxpayer.

“The company profited from that behavior and so did the board members,” he said.

‘People have to feed their families’

As coronavirus cases surged in Virginia earlier this year, state officials went shopping for books. The health department ordered 53 copies of McChrystal’s “Team of Teams,” for a total cost of more than $1,000, July procurements records show.

The supplier was McChrystal Group, the boutique consulting firm founded in 2011 by the retired general. It has since grown to about 85 employees, he said.

The firm, built on the idea that McChrystal and his colleagues “could capture the lessons they learned in counterterrorism and translate them into the private sector,” has advised clients including Bank of America, the National Basketball Association, Monsanto and MedStar Health. Its government work began two years ago, McChrystal said, when the firm ran leadership training for the Department of Homeland Security’s cyber unit and for the U.S. Secret Service.

Then a new opportunity arose. Last year, the firm began advising state and local governments on covid-19 response — one of many consulting companies that secured no-bid contracts to fill gaps in public health agencies overwhelmed by the crisis.

McChrystal Group’s services focused especially on leadership development based on the principles in “Team of Teams,” state records show. A Virginia health spokeswoman, Tammie Smith, said McChrystal’s books were purchased for the department’s work on “culture change dynamics.” All told, McChrystal Group has billed the state more than $5.7 million over the last 20 months, records show.

The firm also consulted on pandemic response for the city of Boston and the state of Missouri, for fees of more than $1.1 million and about $2.2 million, respectively.

In those cases, hardly any of the consultants identified in the contracts had public health experience, as indicated by their LinkedIn profiles. Two were recent Yale graduates and members of the football team, which McChrystal takes on a trip each year to the battlefield at Gettysburg.

“We weren’t experts in public health,” McChrystal acknowledged. “But we’re good at getting networks to communicate and come out with the right answer and implement.”

He added, “The problem in covid has never been a lack of public health knowledge. The problem in covid has been the inability of larger organizations to share information, and the lack of political leadership to do what we already know is the right answer.”

Marissa Levine, a former Virginia health commissioner who now directs the University of South Florida’s Center for Leadership in Public Health Practice, questioned that premise. Leadership training for public health requires specialized expertise, she said, because it differs from a business, being accountable not to shareholders but to “everyone in a community.”

But some officials said the firm’s services were crucial. The consultants served as the “nerve center of our response,” said Brian P. Golden, director of the Boston Planning and Development Agency. They led an 8 a.m. call and then managed tasks arising from the conversation, he said. “McChrystal Group was the enforcer all day.”

“We certainly could have figured this stuff out ourselves, but we had no time to waste,” Golden said.

The firm’s responsibilities were sweeping. The contract provided that McChrystal Group would “review and advise of all city plans.”

A spokeswoman for Marty Walsh, the former mayor who hired McChrystal’s team in Boston and now serves as Biden’s labor secretary, did not respond to a request for comment about the firm’s performance or the “weekly one-on-one executive consultation” promised to him in the contract. McChrystal said Walsh recently dined at his home in Alexandria, Va.

The retired general said his firm comes comparatively cheap. “We cost a fraction of what a traditional consulting firm comes in,” he said. His own pay is a “fraction” of what he would make in a larger company, he said, while declining to say how much he earns.

The fees in Missouri, about $250,000 per month, struck a former senior state official as too high for a small number of consultants. The former official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to address the response candidly, said the consultants interfered with the ordinary chain of command, causing more disruptions than upgrades. Kelli Jones, a spokeswoman for the governor, said the consultants helped “pull teams together within our state government to drive quick and effective action across every line of effort in the covid-19 response.”

Many of the firm’s recruits come from Yale, where McChrystal has taught since 2010. “You fish in the pond you’re standing around,” he said.

McChrystal’s course on leadership is “almost legendary,” said James A. Levinsohn, who directs the Yale institute where McChrystal teaches. Student evaluations reviewed by The Post reflect that status. One said it was useful “if you have any aspirations to climb a corporate ladder, serve in a leadership position, or just be a valuable member of team.” Complaints were sparse, but one bemoaned the complexity of the text assigned from Confucius, the ancient Chinese philosopher.

Central to McChrystal’s philosophy is the belief that all Americans should serve their country, inspiring his pro bono work as board chairman for Service Year Alliance, a nonprofit seeking to expand opportunities for a year of paid, full-time service. The retired general’s support has been a major asset, said John Bridgeland, the nonprofit’s vice chairman and a former director of the White House Domestic Policy Council.

Bridgeland said it was only natural for McChrystal to take on corporate work as well.

“People have to feed their families,” he said.

Pro-choice protesters demonstrated outside the Texas State Capitol on September 1. (photo: Sergio Flores/WP/Getty Images)

Pro-choice protesters demonstrated outside the Texas State Capitol on September 1. (photo: Sergio Flores/WP/Getty Images)

Businesses across the leisure and hospitality industry are trying to staff up as the economy reopens, but they're having a hard time getting people to come work for them. (photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

Businesses across the leisure and hospitality industry are trying to staff up as the economy reopens, but they're having a hard time getting people to come work for them. (photo: Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

According to witnesses, soldiers have been deployed in Conakry. (photo: AFP)

According to witnesses, soldiers have been deployed in Conakry. (photo: AFP)

Defence ministry says an attack on the presidential palace by mutinous forces has been put down.

But Guinea’s defence ministry said that an attack by mutinous special forces on the presidential palace had been repelled on Sunday. It was not immediately clear who held power.

Earlier, unverified videos shared on social media apparently showed President Alpha Conde being surrounded by soldiers. His whereabouts were unclear.

This followed earlier reports of heavy gunfire in Conakry near the presidential palace though it was unclear who was responsible.

Soldiers claim to take power

After seizing the airwaves, the mutinous soldiers vowed to restore democracy. Colonel Mamadi Doumbouya sat draped in a Guinean flag with a half dozen other soldiers in uniform alongside him as he read the statement, saying: “The duty of a soldier is to save the country.

“The personalisation of political life is over. We will no longer entrust politics to one man, we will entrust it to the people,” Doumbouya said, adding that the constitution would also be dissolved and borders closed for one week.

Doumbouya, who has headed a special forces unit in the military, said he was acting in the best interests of the nation of more than 12.7 million people. Not enough economic progress has been made since independence from France in 1958, the colonel said.

“If you see the state of our roads, if you see the state of our hospitals, you realise that after 72 years, it’s time to wake up,” he said. “We have to wake up.”

The defence ministry said the attempted uprising had been put down.

“The presidential guard, supported by the loyalist and republican defence and security forces, contained the threat and repelled the group of assailants,” it said in a statement.

“Security and combing operations are continuing to restore order and peace.”

Guinean journalist Youssouf Bah told Al Jazeera the situation was very fluid.

“Since the coup plotters’ statements on the national television, the opposition supporters have taken to the streets and thousands of youth are dancing, welcoming them,” he said, speaking from Conakry.

Bah described Doumbouya as a “popular military officer among most of the presidential guard”.

“The city is divided,” he added. “One part is supporting the coup plotters, and the other part has clashes between different groups. So it’s very difficult to understand exactly what is happening.”

Videos shared on social media had earlier shown military vehicles patrolling Conakry’s streets and one military source said the only bridge connecting the mainland to the Kaloum neighbourhood, where the palace and most government ministries are located, had been sealed off.

Al Jazeera’s Nicolas Haque, reporting from Dakar in neighbouring Senegal, said troops had been deployed in downtown Conakry and ordered residents over loudspeakers to remain indoors.

Haque said the area near the Hotel Kaloum was the scene of shooting and President Conde was reportedly nearby at the time.

“This comes a week after the national parliament voted an increase in budget for the presidency and parliamentarians, but a substantial decrease for those working in the security services like the police and the military.”

Disputed elections

Conde won a third presidential term in a violently disputed election last October. He ran after pushing through a new constitution in March 2020 which allowed him to sidestep the country’s two-term limit, provoking mass protests.

Dozens of people were killed during demonstrations, often in clashes with security forces. Hundreds were also arrested.

Conde, 83, was then proclaimed president on November 7 last year – despite complaints of electoral fraud from his main challenger Cellou Dalein Diallo and other opposition figures.

A former opposition activist himself, Conde became Guinea’s first democratically elected president in 2010 and won re-election in 2015 before doing so again last year. Critics, however, accuse him of veering towards authoritarianism.

Haque said the growing discontent with Conde was rooted in his inability to unite the population – the majority of who are Fulanis but are ruled by the minority Malinke ethnic group.

“It’s interesting to see officers go to the national television on social media calling for unity and the reason being is because the military remains divided,” he said. “There are still members that support Alpha Conde and will go out of their way to defend the president.”

Colonel Mamadi Doumbouya is himself a member of the Malinke group.

Guinea has witnessed sustained economic growth during Conde’s decade in power thanks to its bauxite, iron ore, gold and diamond wealth, but few of its citizens have seen the benefits.

An owl rescued from Lake Tahoe Wildlife Care Center recuperates at a bird sanctuary. (photo: Don Preisler)

An owl rescued from Lake Tahoe Wildlife Care Center recuperates at a bird sanctuary. (photo: Don Preisler)

Wildfires take a devastating toll on local animals. A Lake Tahoe refuge made sure its creatures didn’t suffer the same fate

They coaxed animals into transport crates, sometimes with inventive methods. “The owl’s treat is a piece of salmon. You know the owl is going to go in the cage to get the piece of salmon,” Erfani said. Being prepared made all the difference. “Within an hour and a half we had evacuated all animals, all staff, and all volunteers from our facility.”

LTWC is one of many animal shelters whose staff scrambled to escape as the Caldor fire, which has now consumed more than 213,000 acres, swept through the Sierra Nevada Range.

On a typical day, LTWC finds and receives injured and sick animals of all kinds – from bears to barn owls – and helps them get back to the wilderness. Sometimes that means mothering baby coyotes until they are ready to hunt on their own, or helping enormous birds of prey regain their ability to fly.

Some animals live permanently at the center, including the fan favorite Em, a bald eagle with a broken wing who has been there since 2015. There’s also Porky the porcupine, who captures hearts with his signature waddle and camera-friendly chow sessions eating corn on the cob.

Erfani says it’s the first time a fire has put their mission in jeopardy.

“Our mission is the rescue, rehabilitation and release,” he said. “But you can’t release animals in a burn scar area because there’s no food source.”

As wildfires worsen across the west, animals are increasingly bearing the brunt, and firefighters, teams of state-funded disaster veterinarians, and rescue centers like LTWC are redoubling their efforts to save whoever they can.

“There’s always been this prevailing mindset that ‘they’ll get out of the way’, or that they can manage if left alone, but that needs to change,” said Dr Jamie Peyton of the University of California, Davis, who is part of a collaborative wildlife search and rescue team founded in 2020 between the university and the California department of fish and wildlife called the Wildlife Disaster Network. “Without human interference, these animals will suffer and succumb, due not only to their injuries but also to the loss of food, water and habitat. It is our obligation to provide the missing link for the wildlife that share our home.”

Yet even with the extra help, not all animals can be saved.

This week a bear called Tender, who captured the public’s heart after his paws were covered in third degree burns in the Caldor Fire, was euthanized due to the severity of his injuries. “That’s never the result we want, but sometimes it’s the only compassionate choice,” said Kirsten Macintyre, a supervising information officer for the California department of fish and wildlife.

Macintyre said the agency had received more reports of burned animals as the intensity and frequency of California’s fires had increased. Larger animals, including black bears and mountain lions, are treated in the agency’s facility whenever possible while smaller animals such as bobcats and skunks are brought to other wildlife rehabilitation centers.

Birds, both wild and domesticated, are often cared for by Michelle Hawkins, the director of the California Raptor Center at UC Davis and a board-certified specialist in avian medicine and surgery.

Hawkins says there’s a misconception that birds can just fly away from incoming infernos. “A lot of people believe that with fires, birds are best off,” she said. “But there are a lot of species of birds that live in one small area of woods for their entire lives and moving out of that area could be extraordinarily stressful for them.”

Birds are also in danger while they roost and sleep. “If a fire blows through at night – which is a lot of activity we have seen here in California – those birds don’t have a chance,” she said. “We saw that last year with our California condors. We lost 11 last year in the fires.”

Already this year there have been more heartbreaking stories. A hawk, electrocuted by downed wires in the Dixie fire, had to be euthanized this week. An owl found by a firefighter succumbed to its injuries before he could get the bird help. “He had it cradled in his arms and it died in his arms,” she said. “They were trying to get it out. He was in tears.”

Hawkins says firefighters are often the first to find an injured bird. Some may have had their feathers singed, rendering them flightless, while others are malnourished or suffering from smoke inhalation.

But for those who are found, the veterinarians and care workers stop at nothing to recuperate them. Others who are too injured for release have permanent homes where they can help educate the public.

Hawkins, who also works with the Wildlife Disaster Network, said Em, the bald eagle evacuated from Lake Tahoe Wildlife Center, was in her team’s care and was settling in well. “He’s got a pretty cool eagle suite at the California Raptor Center right now,” she said. “We set him up in his own house with lots of perches and enrichment for him.”

“He is just a lovely bird,” she added, and a testament to how important it was to be ready for fire. The center’s evacuation plan was what ensured his safety and that of the staff that saved him. “Just because you haven’t been in the path of a fire now doesn’t mean you won’t be in the future,” she said. “It’s extraordinarily important for all of us and a lesson we all have to take to heart – for all the animals in our care.”

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment