Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

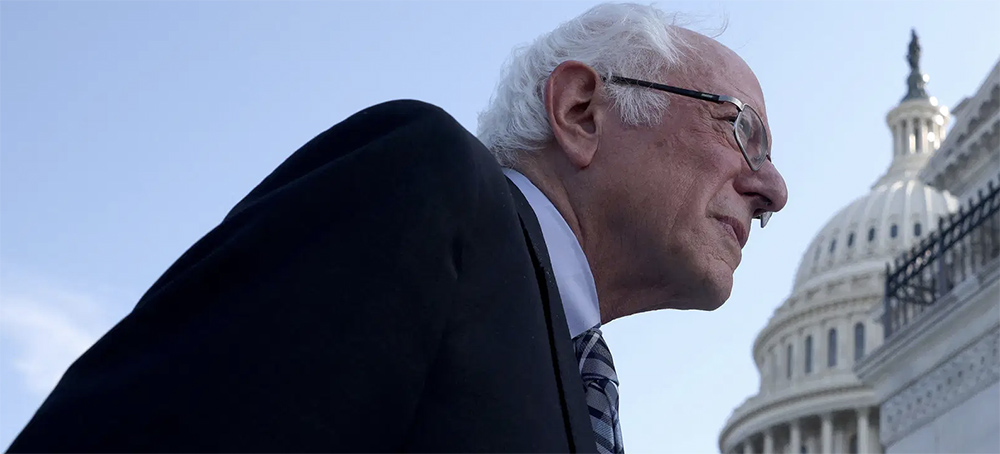

One need look no further than the masked audience members to see how much has changed since Sanders last campaigned in Iowa on his two presidential runs in 2016 and 2020. The event is outdoors, socially distanced and many in the crowd are wearing face coverings—a clear reminder of the coronavirus pandemic that ground the country to a halt a year and a half ago, killing more than 600,000 Americans and millions of jobs.

For Sanders, political opportunity has come from tragedy. The pandemic pushed both the country and the Democratic Party to embrace the Vermont Senator’s career-long push for government aid programs. President Joe Biden came into the Oval Office determined to prove that, in the depths of the pandemic and after the chaotic Trump Administration, the government could be a force for good. And when Democrats narrowly reclaimed the Senate last January, Sanders took over the powerful Senate Budget Committee and became a crucial partner to passing Biden’s objectives.

That’s what brought Sanders to Iowa this time around. He reached an agreement with Biden in July for a $3.5 trillion avalanche of federal spending over the next decade that would make childcare and community college more affordable, expand Medicare and authorize a federal paid family leave program—all largely paid for by taxing the wealthy and corporations. Now, he’s trying to sell the budget bill to the public. “We can not only address these awful problems,” he tells the crowd, “but we can move this country forward in a very different and positive direction.”

After three decades in Washington, Sanders is at the height of his powers, and on the cusp of delivering a version of the policies he’s advocated for his entire career. But in order to do that, one of the Senate’s oldest progressive agitators has relied on a timeless legislative skill rarely mentioned in his campaign speeches: compromise. While Sanders initially envisioned a $6 trillion spending bill, he settled for nearly half that in order to get all members of his party on board. “This is the most consequential piece of legislation for working people since the 1930s,” Sanders says in an interview with TIME at a diner in Cedar Rapids, banging his hand on the wooden picnic table between every word for emphasis. “If you’re a progressive who has spent your entire life fighting for working people, fighting for children, fighting for the elderly, fighting for the climate, what you say is, ‘Well, it’s not all that I want.’ We’ve got to continue the fight, but we have accomplished an enormous amount.’”

Progressives watching the process say he is teaching them how to govern, a lesson that could have a longer legacy than the bill. “It’s a necessary maturation of the progressive movement to go from protest to government,” says Joseph Geevarghese, the Executive Director of Our Revolution, a political grassroots organization that grew out of Sanders’ first presidential campaign. “And that’s the process that we’re in the middle of, is learning that we can’t just be outside on the streets raising hell.”

The $3.5 trillion package is far from a done deal, and Sanders will soon face the ultimate test. Committees in the House and Senate are currently drafting language, but with moderate lawmakers in both chambers skeptical of the price tag, it’s becoming increasingly clear that progressives are unlikely to get everything they want. There are weeks of intense negotiations ahead. But if Sanders can get a version of this bill to Biden’s desk, he will have played a key role in passing the most expensive reshaping of the country’s social safety net in over half a decade—and perhaps cemented his own legacy as both firebrand and legislator.

‘A lot of heartburn’

As soon as Biden introduced his blueprint for spending on infrastructure and the “care economy” last spring, Sanders began strategizing with progressives in Congress on how to maximize their leverage.

While Sanders wanted a $6 trillion bill, he knew it was unrealistic. He sensed from both his personal relationship with Biden and the policies the President was putting forward—like two years of free community college and universal access to pre-K—that he had a better chance of getting at least some of what he wanted if he was willing to come down on the price.

Throughout the spring, Sanders huddled with the leadership of the Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) to come up with their five top priorities: investments in home care services and affordable housing; lower drug prices and Medicare eligibility; and creation of climate jobs. Rep. Ilhan Omar of Minnesota, the whip of the CPC, recalls meeting with Sanders over a dozen times. “The dollar amounts were really not the focus of the conversation, but more in regards to getting… a bill that meets the moment, and making sure that the Progressive Caucus was using its influence,” she says.

Sanders also pressured the White House: In the Oval Office in July, he pushed Biden to include hearing aids, eyeglasses, and dental coverage in the Medicare expansion, and Biden agreed. “Though it was not in the original Families Plan announced in April, Senator Sanders repeatedly pressed the President to embrace his proposal to expand Medicare coverage for dental, hearing aids, and vision,” says a senior White House aide. “He made that case passionately, strongly in the Oval, and the President gave his full backing.”

Sanders’ strategy, says one Congressional aide familiar with the dynamics of progressive wing, was to “lay out a left flank marker that would then have gravity, and pull the debate to the left.” Progressives credit Sanders with getting what they so far view as a favorable compromise. “I don’t think we would have ended up with three and a half trillion,” the aide says, “If [Sanders] hadn’t done that.”

After weeks of negotiating with both the White House and his own committee, Sanders says the $3.5 trillion number was reached thanks to “a lot of talking and a lot of heartburn.” For him, it’s a mixed bag. Ideas he had been championing for years, like a wealth tax and Medicare for All, were not in there. But other progressive wish list items, like an extension of the child tax credit and tax increases on the wealthy, were included. “All of the major provisions remain in the bill: that is the good news,” he says. “The bad news is, we are not funding them, at this point, for as long a period as I want.”

‘We’ve got to be as pragmatic as possible’

Sanders acolytes hope his leadership will pave the way for the progressive movement to become an effective governing force, crafting legislation within the system rather than protesting outside it.

In July, Our Revolution, which according to a spokesperson has over 500,000 members organized in thirty states, rebranded itself as a group of “pragmatic progressives.” Instead of rallying around big ideas like the Green New Deal or Medicare for All, they will now advocate for more incremental changes. During the August recess, they demonstrated in front of moderate lawmakers’ offices—in favor of the $3.5 trillion package. “Our job as organizers is trying to educate people, like, ‘Look, we’ve got to be as pragmatic as possible,” says Geevarghese, the group’s Executive Director. Geevarghese largely credits Sanders with paving that path for the group. “What Bernie has done I think quite artfully as a movement leader is not just throw bombs or issue critiques, but actually get our ideas to be considered seriously and then make… pretty significant progress in advancing them,” he says.

In the coming weeks, that progress could slow. The committees tasked with drafting the components of the legislation have been working furiously to present a complete version for Congress to pass by the end of September at the earliest. Democrats are trying to pass it through a budgetary process called reconciliation, which they can do along party lines. But with such small margins in the House and Senate, and no support from Republicans, there is no room for any defections, and the moderate wing of the party is gearing up for a challenge. West Virginia Senator Joe Manchin has already said the price tag will be a problem. “I, for one, won’t support a $3.5 trillion bill, or anywhere near that level of additional spending, without greater clarity about why Congress chooses to ignore the serious effects inflation and debt have on existing government programs,” he wrote in a September 2nd op-ed in the Wall Street Journal. One Democratic strategist familiar with Senate dynamics predicts that, despite Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s vow that the chamber is moving “full speed ahead” with $3.5 trillion, it may actually have the support of an estimated 30 Senators. “Manchin is just the one sort of taking the arrows right now,” says the strategist. “I would bet a lot of money that the deal comes closer to $2-2.4 trillion [instead of] $3.5 trillion.”

All of that signals more compromise ahead for the progressive wing. The House Ways and Means Committee, for example, which is drafting the Medicare portion of the bill, voted on September 10 to expand hearing, vision and dental benefits under Medicare, but the latter would not be provided until 2028, which is later than Sanders wanted. And even that vote did not get unanimous Democratic support: Rep. Stephanie Murphy of Florida voted against these measures, claiming that the party has not provided an adequate explanation for the cost or funding of these programs. “If you don’t compromise, the bill’s not going to pass, and if the bill doesn’t pass, nothing gets done,” says one Congressional aide associated with the moderate wing of the Democratic party. “You can disagree with Joe Manchin or Kyrsten Sinema all day, but if they say, ‘I will not vote for XYZ, you can’t just ignore that, because the reality is this is going to be a politically tough vote, whether you’re in a tough state or a tough district.”

This will test Sanders’ ability to keep progressive support behind the package as patience frays with continually lowering the cost to appease moderates. Progressive groups like the Sunrise Movement, who want at least $10 trillion, have already deemed the current version inadequate. Members of the CPC are also signaling they’re unwilling to go further. “For us, it’s been really clear that that is the floor, not the ceiling, and that [$3.5 trillion] is considered a compromise by a lot of us,” says Rep. Omar.

Some of the voters Sanders was speaking to in Iowa—many decked out in Bernie campaign gear—seem disappointed, too. “I think this time they need to stand their ground,” an Iowan sporting a Bernie Sanders pin who identified himself as Flavio Hidalgo says after the Cedar Rapids rally. “We should push, not compromise, because that’s what the Democrats usually do, and then we don’t get anything. You get watered down things.” Sanders assures another voter in Cedar Rapids who asks if he would support a lower price tag that there will still be a $3.5 trillion package at the end of the day. “I’ve already compromised,” he said.

The million dollar question—or perhaps the $3.5 trillion question—is where Sanders draws his red line. If the moderates stand their ground and the only way to get these priorities into law is on a smaller scale than he wants, will his pragmatic legislative side prevail over the progressive rabble-rouser? So far, he’s not showing his cards. “If there’s a bill that doesn’t do very much, absolutely I’m prepared to vote no,” he says. “But when you have a bill, yes it does not go anywhere near as far as I would like to go, but it is very very consequential, I’m proud to be supporting it.”

Left: On Nov. 20, 1971, demonstrators demanding a woman's right to choose march to the U.S. Capitol for a rally seeking repeal of antiabortion laws. Right: On Sept. 11, 2021, abortion rights activists rally at the Texas State Capitol in Austin. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images/AP)

Left: On Nov. 20, 1971, demonstrators demanding a woman's right to choose march to the U.S. Capitol for a rally seeking repeal of antiabortion laws. Right: On Sept. 11, 2021, abortion rights activists rally at the Texas State Capitol in Austin. (photo: Jordan Vonderhaar/Getty Images/AP)

At the time, abortion was effectively illegal in Texas — unless a psychiatrist certified a woman was suicidal. If the woman had money, we’d refer her to clinics in Colorado, California or New York. The rest were on their own. Some traveled across the border to Mexico.

At the hospital that year, I saw three teenagers die from illegal abortions. One I will never forget. When she came into the ER, her vaginal cavity was packed with rags. She died a few days later from massive organ failure, caused by a septic infection.

In medical school in Texas, we’d been taught that abortion was an integral part of women’s health care. When the Supreme Court issued its ruling in Roe v. Wade in 1973, recognizing abortion as a constitutional right, it enabled me to do the job I was trained to do.

For the next 45 years — not including the two years I was away in the Air Force — I was a practicing OB/GYN in Texas, conducting Pap smears, pelvic exams and pregnancy check-ups; delivering more than 10,000 babies; and providing abortion care at clinics I opened in Houston and San Antonio, and another in Oklahoma.

Then, this month, everything changed. A new Texas law, known as S.B. 8, virtually banned any abortion beyond about the sixth week of pregnancy. It shut down about 80 percent of the abortion services we provide. Anyone who suspects I have violated the new law can sue me for at least $10,000. They could also sue anybody who helps a person obtain an abortion past the new limit, including, apparently, the driver who brings a patient to my clinic.

For me, it is 1972 all over again.

And that is why, on the morning of Sept. 6, I provided an abortion to a woman who, though still in her first trimester, was beyond the state’s new limit. I acted because I had a duty of care to this patient, as I do for all patients, and because she has a fundamental right to receive this care.

I fully understood that there could be legal consequences — but I wanted to make sure that Texas didn’t get away with its bid to prevent this blatantly unconstitutional law from being tested.

Though we never ask why someone has come to our clinic, they often tell us. They’re finishing school or they already have three children, they’re in an abusive relationship, or it’s just not time. A majority are mothers. Most are between 18 and 30. Many are struggling financially — more than half qualify for some form of financial aid from us.

Several times a month, a woman confides that she is having the abortion because she has been raped. Sometimes, she reports it to the police; more often, she doesn’t.

Texas’s new law makes no exceptions for rape or incest.

Even before S.B. 8, Texas had some of the most restrictive abortion laws in the country. That includes a 24-hour waiting period, meaning a woman has to make at least two visits to our clinic. Ultrasound imaging is mandatory. Parental consent is required for minors, unless they obtain court approval.

And yet, despite the restrictions, we were always able to continue providing compassionate care up to the legal limit of 22 weeks. It meant hiring more staff, everything took longer, but we managed.

Until Sept. 1.

Since then, most of our patients have been too far along in their pregnancies to qualify for abortion care. I tell them that we can offer services only if we cannot see the presence of cardiac activity on an ultrasound, which usually occurs at about six weeks, before most people know they are pregnant. The tension is unbearable as they lie there, waiting to hear their fate.

If we detect cardiac activity, we have to refer them out of state. One of the women I talked with since the law took effect is 42. She has four kids, three under 12. I advised her that she could go to Oklahoma. That’s a nine-hour drive one way. I explained we could help with the funding. She told me she couldn’t go even if we flew her in a private jet. “Who’s going to take care of my kids?” she asked me. “What about my job? I can’t miss work.”

I understand that by providing an abortion beyond the new legal limit, I am taking a personal risk, but it’s something I believe in strongly. Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, my clinics are among the plaintiffs in an ongoing federal lawsuit to stop S.B. 8.

I have daughters, granddaughters and nieces. I believe abortion is an essential part of health care. I have spent the past 50 years treating and helping patients. I can’t just sit back and watch us return to 1972.

'I don't see a way that we can truly have people returning to work, especially women, in the numbers that we need if we are not providing for child care,' Rep. Katherine Clark (D-Mass.) said. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

'I don't see a way that we can truly have people returning to work, especially women, in the numbers that we need if we are not providing for child care,' Rep. Katherine Clark (D-Mass.) said. (photo: Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The return to classrooms was supposed to be a turning point for women, whose participation in the labor force plunged to its lowest level in more than three decades during the pandemic.

After 18 months of shutdowns, online learning and canceled summer camps, the return to classrooms was supposed to be a turning point for women, whose participation in the labor force plunged to its lowest level in more than three decades during the pandemic. But as Covid-19 cases rose in the summer, more than 40,000 women dropped out of the labor force between July and August, even as Americans flocked back to work, government data shows. Men returned to the job over that period at more than three times that rate.

That’s lent new ammunition to the Biden administration and Democratic lawmakers in their push to spend hundreds of billions of dollars to overhaul the nation’s child care industry to make it more accessible and affordable, arguing that doing so is the only way to get families back on track. They worry about a repeat of last September, when more than five times as many women as men fell out of the workforce.

“I don’t see a way that we can truly have people returning to work, especially women, in the numbers that we need if we are not providing for child care,” Rep. Katherine Clark (D-Mass.), a member of the House Democratic leadership, said in an interview. The latest jobs numbers, she said, “are a red flashing light that now is the time to invest in women in our workforce.”

Republicans say the price tag — $450 billion — is way too steep and accuse the Democrats of trying to destroy a viable, privately run business in favor of a government-controlled system. Even some Democrats complain that the legislation, which is part of the $3.5 trillion package that Democrats are trying to steer through Congress, would give benefits to higher-income families who don’t need it.

In the short term, the main area of concern is the coronavirus itself and how to tackle it so parents feel comfortable sending their older kids to school and leaving younger ones at day care. That fear of kids catching the virus, paired with the persistent uncertainty over whether schools might have to shut their doors if students or faculty need to quarantine, is enough to keep some parents out of the workforce regardless of whether the schools ever close down, economists say.

“Schools are our Achilles' heel,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist at Grant Thornton. As for women’s workforce participation, she added: “We really can’t resolve it until we know kids can safely be back in school consistently.”

Coronavirus cases have been spreading in schools across the U.S. since July, when the first students returned in person. As of Sept. 13, nearly 1,700 schools across 386 districts in 38 states had shut down in-person instruction, according to the data service Burbio, which is tracking 1,200 school districts nationwide, including the largest 200. The company found that schools move to virtual instruction more than half the time, while nearly four in 10 closures led to no instruction at all.

The biggest worry is for women with young children, who have had the hardest time staying attached to the workforce throughout the pandemic, research shows. Women with kids under age 6 made up 10 percent of the workforce in February 2020 but accounted for nearly one-fourth of the unanticipated employment loss, according to new research from Melinda Pitts, a research center director with the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

The longer-term focus for Democratic lawmakers and the Biden administration is on how to shore up the child care industry more broadly and help it recover from the pandemic. Overall employment in the field nationwide has shrunk by more than 12 percent since February 2020, leaving nearly 127,000 workers out of a job, Labor Department data shows. The sector — where 95 percent of all workers are women — has shed more jobs each of the past two months, including 5,900 in August.

Investments in the industry would have cascading benefits, supporters say, by helping parents get back to work and increasing economic activity now while setting children up to stay in school longer and earn more in their jobs as adults.

The focus of President Joe Biden’s proposed $450 billion in investments is two-fold: funds for child care providers to help them cover costs and improve workers’ pay, as well as money for families, in part to ensure that no one pays more than 7 percent of their income on care for kids under age 5.

“It’s so critically important we get schools reopened, but it’s also critically important that we handle this child care issue,” Rep. Mikie Sherrill (D-N.J.) said. Sherrill led a successful push to amend the House version of the budget package during committee markup so the 7 percent cap on costs is applied for all families, not just those making less than 150 percent of their state’s median income, as Biden had initially proposed.

“Congress needs to understand that moms losing ground, that’s the American middle class losing ground,” Sherrill said. “So while this is a pro-women and a pro-child policy, because we want quality child care, this is also, importantly, a pro-growth policy for our economy.”

Republican lawmakers have pushed back, arguing that the plans are overly generous and would limit parents’ choice in their children’s care while asserting a role for government in an area that they feel the private sector should continue to run.

Rep. Virginia Foxx (R-N.C.), the top Republican on the House Education and Labor Committee, which has been discussing the child care aspects of the bill, said at a hearing that lawmakers should be “focused on ensuring hard working taxpayers can find the best care for their children rather than blindly throwing money at the problem and calling it a solution.”

And the push to lift the income limits on which families can qualify for the 7 percent cap, though it won support from a broad coalition of Democrats, garnered some criticism from within the party — including from Rep. Bobby Scott (D-Va.), who chairs the committee. Scott said he reluctantly accepted the amendment only because “without it, the members of the committee are threatening to jeopardize the entire bill.”

A large majority of voters support the proposals. Two in three registered voters, or 66 percent, said they somewhat or strongly support federal funding for affordable child care being included in the Biden spending package, according to a POLITICO/Morning Consult poll from late last month. That includes 87 percent of Democrats and 44 percent of Republicans.

The Biden administration on Wednesday released a report outlining what it sees as the economic case for expansive federal investments in child care, arguing that the current system leads to “chronic underinvestment” in kids and hampers working parents’ abilities to contribute fully to the economy.

The report highlights how the U.S. lags its peer countries in women’s labor force participation and cites a study finding that a dollar invested in pre-school — which Biden is seeking to make free and universal — pays itself off more than nine times over in terms of the benefits it brings to society.

“For so many working people, and for women in particular, child care is a prerequisite for being able to work,” Vice President Kamala Harris said at an event at the Treasury Department unveiling the report. “If we intend to fully recover from the pandemic, if we intend to fully compete on a global scale, we must ensure the full participation of women in the workforce.”

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis Collins. (photo: Getty Images)

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis Collins. (photo: Getty Images)

Appearing on CBS's "Face the Nation," Collins was asked by host Margaret Brennan whether he agreed with a Food and Drug Administration official who recently placed teachers in the high-risk category.

"I think they could be seen in that space. They are after all, in circumstances — especially if they're in classrooms with kids under 12 who can't be vaccinated — where they are at higher risk of exposure than most of the rest of us. So maybe in that regard, they kind of fit into the same category as health care providers," Collins said.

Brennan asked if this reasoning also placed someone like her, who lives with children who are not eligible to be vaccinated, at a higher risk.

"Margaret, that is a great question and I think that is one of the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] will probably have their committee discuss in some seriousness on Wednesday and Thursday because yes, you are in a circumstance with younger kids who can't be immunized, where it is more likely that you could be exposed than somebody who's living alone," the NIH director said.

Brennan also asked Collins whether those who are now eligible for a third booster shot could receive a Pfizer dose if their initial doses had come from Moderna or Johnson & Johnson.

"We're gonna know more about that just in the course of the next two or three weeks. Tight now we don't have the answer," Collins said. "Moderna and J&J by the way have also submitted their booster data so it's likely that [the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)] will be able to have a comment on that pretty soon."

"Let's be clear. The vaccines right now in the U.S. are doing a great job of protecting people against severe disease, hospitalization. What we're worried about is that's beginning to erode and we're seeing more breakthrough cases and we don't want to get behind this virus we want to stay ahead of it."

An FDA advisory panel on Friday recommended a third Pfizer booster dose for the elderly and other high-risk groups.

Sanchez organizes diapers and wipes for her daughter in their new apartment, which they moved into earlier this month. She is expecting another child later this year.

Sanchez organizes diapers and wipes for her daughter in their new apartment, which they moved into earlier this month. She is expecting another child later this year.

Women who apply for welfare often have to identify who fathered their children and when they got pregnant, among other deeply personal details. State governments use that information to pursue child support from the dads — and then pocket the money.

This spring, she applied for welfare.

Sanchez, who is 33, expected more than financial assistance from the state — in part because she was distantly aware of the history of welfare reform, a federal law that passed 25 years ago this summer. Given that legislation’s emphasis on putting welfare recipients to work, she said, she thought that welfare officials would push her to get a new job: “In fact, I really hoped they’d help me with that.”

Instead, the New Mexico Human Services Department caseworker who called the next day fixated on an unexpected question: Who was baby Avery’s biological father?

You can’t get public assistance if you don’t name your child’s father, the caseworker said.

“She was really adamant about it,” Sanchez said. “It was all she wanted to talk about: the dad.”

In July, a form arrived in the mail notifying Sanchez that if she wanted a small amount of aid — $357 a month — to help pay her motel bill and replace her possessions, she needed to list her baby’s father’s current and former addresses; his employer’s address; his vehicle’s make, model, year, color and license plate number and the state where it was registered; his bank account number; any real estate or other assets he might have; and the addresses of his mother, father and other relatives and friends. She was also asked to provide, under penalty of perjury, the date she believed she got pregnant and why she believed that to be the correct date.

The state of New Mexico, in accordance with the 1996 welfare reform law, intended to use these details to find the dad and force him to make child support payments — much of which the state would then pocket as reimbursement for providing Sanchez with welfare.

But Sanchez has a fragile co-parenting relationship with Avery’s father that she worries could be torn apart by such a disclosure. He’s been driving into Albuquerque most weekends from outside the city to spend time with their daughter, which is a tentatively positive situation, she said. He is in recovery from a drug addiction, and Avery has started calling him “dada.”

If Sanchez outs him to child support agents, she worries, they could suspend his driver’s license for failing to make timely payments — and he’d no longer be able to visit his family, which she fears might cause him to relapse.

It’s a practice with deep roots in U.S. history: Under the bastardy laws of colonial times, a poor woman who gave birth out of wedlock could be jailed or publicly whipped until she named her baby’s father, or until he came forward to shoulder the cost of raising their child.

More than two centuries later, a similar if less violent legal arrangement was included in the 1996 law that overhauled America’s premier cash assistance program for the poor, which was renamed Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, or TANF. The new law said that in order to get federal anti-poverty funding, states would be required to go after fathers of children whose mothers had applied for welfare, in an attempt to get them to pay child support to the government as repayment for those welfare dollars.

Then-President Bill Clinton said this now much-overlooked provision of the legislation would contribute to “the most sweeping crackdown on deadbeat parents in history.”

To this day, almost every parent who applies for federal welfare assistance (in the large majority of cases it is a single mother, and this story refers to those affected as “mothers”) must first divulge everything she knows about the biological father of her children.

For struggling mothers in New Mexico, a state that often ranks last in the U.S. in child poverty and well-being, this federal requirement means that they must either forgo desperately needed assistance for their children or risk complicating what are often already fraught, and sometimes abusive, relationships with their children’s fathers, if they’re even in contact with them.

It also means that contrary to the popular understanding of child support — that it is intended to go to children — more than $1.7 billion in child support collected from fathers in 2020 was seized by federal and state governments as repayment for mothers and children having been on welfare, according to a ProPublica analysis of federal Office of Child Support Enforcement statistics. Close to 3 million of the nation’s poorest families had child support taken from them last year, amid the pandemic, for this reason. (Most other child support cases are initiated through a divorce or a legal action by the mother; for the majority that don’t involve a mom who has received TANF, the money does go to the kids.)

“It distorts the meaning of child support: You’re asking parents to ‘support their children,’ and then you take the money?” said Vicki Turetsky, who served as the federal child support commissioner during the Obama administration, and who, a mother herself, once received public assistance. “It sours everybody on the purpose of child support, and the purpose of government.”

During the pandemic, the IRS and state child support agencies even redirected stimulus money that had been headed to poor fathers into government coffers instead, on the grounds that they owed child support on behalf of a family that had previously received welfare. A ProPublica analysis of OCSE statistics shows that federal and state governments pocketed roughly $684 million more in child support from these fathers in 2020 than in 2019, which experts said is mostly attributable to the dads’ stimulus checks being intercepted. None of that money went to women and children.

Under the welfare reform law, federal funding for states to spend on assistance for the poor was also frozen at mid-1990s levels, and has not been increased since to account for inflation or changes in population or poverty rates. Yet places like New Mexico, Arizona and Nevada look a lot different today than they did then, with an influx of immigrants and young people nearly doubling the region’s population. The cost of living here has skyrocketed, and with it family need.

Still, funding for welfare remains the same, and as a result, the aid that these Southwestern states can offer per poor child has plummeted.

This fall, as the pandemic and the Biden administration’s stimulus plans have renewed interest in the question of direct cash assistance for the poor, ProPublica will be revisiting the welfare law on its 25th anniversary, investigating states where the diminishing “block grant” of federal funds and changing demographics have resulted in harmful and sometimes bizarre approaches to providing — and then taking back — money for the poor.

More than a dozen mothers in New Mexico spoke to ProPublica about their experiences with cash assistance, as did former Human Services Department lawyers and caseworkers who handled welfare applications. The moms described it as humiliating and sometimes terrifying to be questioned about their sexual histories by agents of the state, in small interview rooms, just to obtain a basic form of government help. Some were required to submit their children to genetic testing in order to receive aid.

Alyssa Davis gave up on applying for public assistance because, she said, “I guess I just wasn’t desperate enough to keep putting up with everything they put you through, as a mother. It’s just not worth it.”

Others fear domestic violence or emotional abuse if they name fathers to the authorities. Caseworkers from multiple states shared instances of mothers saying that dads had threatened to retaliate by killing or kidnapping the mom or her child.

One worker not in New Mexico said in an email that in a recent case, an absent father told a woman applying for public assistance that “if she ever mentions his name on anything, that is the last time she would ever be able to say his name.”

For many mothers, though, the harm is subtler: Fathers may retaliate by withholding informal support, like cash, gifts to the kids or babysitting help. Or a mother may know that her former partner is in a precarious financial situation, and would be ruined by the government garnishing up to 65% of his paycheck — and threatening him with jail time if he can’t or won’t pay up.

In August, the New Mexico Human Services Department cut Sanchez’s monthly benefit from $357 to $268 due to her failure to cooperate with child support, her case documents show; the agency may soon slash the amount to zero.

“And who suffers when benefits are cut? The child,” said Teague González, director of public benefits for the New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty. “That’s money for rent, food and diapers. Children shouldn’t be penalized for what either parent is or isn’t doing.”

Betina McCracken, acting director of the department’s Child Support Enforcement Division, said in an interview that this practice is required by federal law and that the agency takes mothers’ experiences — particularly domestic violence — seriously. Abuse cases are immediately flagged so that caseworkers can handle them with care and confidentiality, and a survivor is allowed to opt out of the child support requirements if she provides a police report or restraining order, or a notarized affidavit attesting to the harm she’d face by naming an abusive father.

McCracken also emphasized that if child support does get set up, it can continue helping the family far beyond the time when the mother is receiving assistance. A child support order should last until a child turns 18, whereas a mom can only get TANF for a few years — because the 1996 welfare reform law allowed states to establish strict time limits for receiving aid.

Also, she said, there can be lasting benefits to children of identifying the father, including a sense of family identity, access to medical history information and Social Security benefits if the dad dies.

As for mothers who complained about how they were questioned by the department, McCracken said that she could imagine how it would feel “if I was in that situation and I had to go in and explain when I had sex, when was the last time, and with whom.” But those details are essential to the task of establishing biological paternity, she said. “We recognize that this is not a comfortable situation.”

Sanchez, after being informed by an advocate about the option to request an exemption from these requirements, submitted forms saying, in part, “I do not want to ruin the relationship by getting child support.” The agency responded weeks later with a notice saying that due to her failure to comply, “Your benefits will be less or stop.”

McCracken said that subjective reasons that a mother might not want to cooperate with child support in order to receive assistance — short of domestic violence or other risk of severe physical or emotional harm to her or her child — are not legally valid. Sanchez’s concerns about the process crushing her fragile family dynamic, for instance, do not meet the standard for opting out, McCracken said.

The practice of confiscating child support payments from the poor persists in part because some policymakers believe that welfare should be considered a loan, to be repaid by the patriarch of the family.

“Legislators suggest to me that if a family gets both TANF and child support, they’re ‘double-dipping,’” said Jim Fleming, president of the National Council of Child Support Directors and president-elect of the National Child Support Enforcement Association. (He noted that he was not speaking on behalf of either organization.) “That argument is still out there,” Fleming said, though it is “becoming more and more of a minority view.”

The practice has also survived because the government benefits from it financially. Child support obtained from these families is a critical source of revenue for many states and counties, said Fleming, who is also North Dakota’s child support director. That point was echoed in interviews with other state child support officials.

But amid the pandemic, many politicians are reimagining the American social safety net: From stimulus checks to child tax credits, the trendy, research-based approach has been to get cash straight to families in need with no strings attached.

In Congress, a pair of Democratic senators are set to introduce a bill this fall that would ban states and the federal government from pocketing child support as “cost recovery” for welfare. The legislation contains some additional federal funding so that state agencies can implement the change without cutting their budgets; in part to win Republican votes, it also includes grants for healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood programs.

“I think there’s the potential for bipartisan support,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen of Maryland, who will introduce the bill along with Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon and Illinois Rep. Danny Davis in the House of Representatives. “The focus of the current system is on collecting money for the government, rather than on strengthening families — which should be our shared goal.”

Less Money to Aid the Poor, but Greater Latitude Over Its Use

The Southwest has been a case study in why welfare should not have been turned into a block grant, experts say.

Nevada, for instance, saw a greater increase in numbers of poor children from 1997 to 2015 than any other state, and Arizona wasn’t far behind; at the same time, those states’ federal aid funds per poor child declined in value by more than 50% due to inflation and demographic changes, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

As a tradeoff for providing states like these with a set amount of funding that would decline in value over time, the Clinton administration promised each state more flexibility over how it could use the dollars, unburdened by federal regulation. The implication was that with greater discretion as to how to address poverty, states would innovate and find ways to do more with less.

But the opposite has been true. Because of their shrinking blocks of funding, states have cut benefit amounts for the poor and set short time limits for receiving assistance. And with their greater flexibility, they have spent the federal money on programs unrelated to direct aid to poor mothers and children — or have asked equally poor fathers to pay the government back.

The practice of taking child support money from these families already existed, but prior to 1996 states had been required to send at least $50 a month of a child support payment to the family before diverting any of it into government coffers. The welfare reform law also allowed states to cut off all aid to mothers, not just a portion, for failure to cooperate with child support. (At least 14 states reduce families’ benefits by a smaller percentage, often 25%, for child support noncompliance; New Mexico is among the majority that will cut the whole amount in some cases.)

Many low-income moms in New Mexico said they lasted just a few months receiving aid because of how often their benefits were cut for not responding quickly enough to a child support mailing or for not taking off work to attend a child support interview.

In August, 1,974 families receiving TANF in the state were sanctioned — meaning their benefits were reduced or ended — for a failure to comply with what child support officials were asking of them, out of a total of roughly 12,000 cases statewide. That means about one in six mothers and children were financially penalized under the child support rules in just one month.

Especially during the pandemic, the TANF program has failed families in part “because of how they sanction you for this really personal thing,” said Micaela Baca, who grew up in foster care and now supports her children in Albuquerque by working 16 hours a day, six days a week, as an in-home caregiver and at a nursing home. Welfare, she added, “could really make our state and our community better, and help bring someone like me up out of poverty. But it’s just not doing that.”

Janel Ahle is pursuing a biomedical engineering master’s degree at the University of New Mexico; she has also studied evolutionary anthropology, Russian and psychology, she said. With her busy academic schedule, she hoped for some help paying for child care and other parenting needs for her children. But she gave up on applying for public assistance because, she said, “I didn’t want to go through with the child support process, because I saw it as the guy who had never been there getting more rights in the matter.”

This was another common fear articulated by mothers who were asked to name fathers to get aid: that an absent dad forced to pay support would spitefully seek custody or greater involvement in medical and educational decisions about the child.

Janel Ahle. “There was shame around applying — part of why the whole thing was hard was the stigma,” she said. “And then they do this to you, too.”

Karmela Martinez, director of the New Mexico Human Services Department’s Income Support Division, which administers TANF, said in an interview that the sanctions imposed on poor mothers for not cooperating with child support are mandated under a New Mexico statute that was enacted in compliance with the 1996 welfare reform law. Any change to the sanctions system would have to be made by the state Legislature, she said.

Martinez also said that the Child Support Enforcement Division is the part of the department responsible for deeming mothers compliant or not, and that once they are found to be noncompliant, sanctions go into effect automatically according to a computer system. In other words, she said, it’s not up to individual Income Support Division caseworkers making subjective decisions to punish moms.

New Mexico does pass roughly half of the average monthly child support payment to kids in TANF cases, according to statistics provided by the department, though it keeps the rest. Some states, including nearby Arizona and Nevada, seize 100% of the money.

New Mexico stands out, though, in part because this practice harms an especially vulnerable population there: It has some of the highest levels of child poverty in the developed world.

It’s also a contentious moment politically for the issue in that state. According to interviews with mothers, state caseworkers and policy experts, New Mexico stiffened its rules for cash assistance under the governorship of Susana Martinez, a Republican who made deep cuts to social programs. But that strict enforcement has largely continued since Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham, a Democrat who promised in 2019 that she would end child hunger statewide, took office. (Both houses of the Legislature are also controlled by Democrats.)

Angelica Rubio, a state representative, has raised the child support issue with the Human Services Department in private meetings, according to interviews with those who were present. But Rubio told ProPublica that there didn’t “seem to be much sense of urgency,” and that the conversations were “pretty rushed and felt like a non-priority.”

The department earlier this month did request $1.7 million in additional funding from the Legislature to fill the budget shortfall that it said would result if it sent more child support payments to families instead of intercepting the money, a reform that Gov. Lujan Grisham’s office said she supports. But McCracken, the acting child support director, said agency officials are still looking at their options and cannot, for fiscal reasons, go so far as to let all child support flow to mothers and children.

There’s also no guarantee that the request for more funds will be approved; the Legislature will be considering the new budget until January.

Tripp Stelnicki, director of communications for Gov. Lujan Grisham, said in an email that the administration “ gets important benefits to families throughout New Mexico without excessive sanctions, restrictions and requirements every single day.” He also pointed out that the governor recently worked to pass legislation modernizing the state’s child support system with the goal of getting more money to children.

Child Support Program Began After Welfare Was Extended to Women of Color

Race has always colored the relationship between welfare and child support.

In the early 1900s, state and local cash assistance for single mothers — often called a “mother’s pension” — was available mostly to widowed white women, not to Black women or unwed moms. As the welfare rolls diversified in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s, many states adopted “man in the house” mandates, which cut aid to women if a man lived in their home who was not their children’s father; these were enforced far more often against Black mothers.

In 1975, the federal child support program was founded with the explicit purpose of getting fathers to repay the government for public assistance that mothers had received.

“It’s not a coincidence that child support was federalized in the decade after the civil rights movement — in other words, in the decade after all these public goods, including welfare, had started being expanded to Black women,” said Daniel L. Hatcher, an expert on poverty at the University of Baltimore School of Law. “We don’t force middle-class or wealthier single women who have received government services, or tax breaks of one sort or another, to pursue child support against the dad if they don’t want to.”

Curshelle Vann, another mother in Albuquerque, said the government “demeans you” about going after child support to repay welfare, especially if you’re Black, Hispanic or Native American.

“I didn’t think they’d be so nasty about the father,” said Vann, who is Black. “If I don’t know where he works or any of that, they shouldn’t cut off money for my children.”

The stigma around the sexual choices of single moms remains pervasive at the welfare office, said Georgette Cooke, who said she doesn’t know who the father of her child is. “Look, it was a one-night stand. I didn’t know I would get pregnant,” she said. “But I’m still the one who has to support my child.”

Georgette Cooke. “My reaction was like, ‘Oh, I need a dad? I need a guy?’ You know?”

Cooke said she considered lying to New Mexico officials, telling them the dad was “Tom Cruise or something.”

She said the state cut off all of her assistance — money she was using for diapers and wipes — for not cooperating with officials in their attempts to name the father.

McCracken, the child support director, said that not knowing the identity of the dad is not a good-cause reason for not cooperating with child support, though as long as the mom keeps communicating with child support agents while they search for him, they may stop requiring her participation after six months or a year if he cannot be found.

Robert Doar, president of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank, was the head of New York state’s child support program when federal welfare reform was passed. He noted that due to the 1996 law’s strong work requirements and the resulting narrowing of cash assistance, TANF has become such a small program that the child support issue affects far fewer mothers and children than it used to.

“Maybe this practice ought to be put out of its misery,” he said, but he added that there remains a legitimate rationale for it: “When a parent needs help from the government because the other parent is not supporting them ... it’s perfectly logical to say to that absent parent, ‘Hey, wait a minute, you ought to pay us back.’”

Doar said that requiring mothers to comply with child support, even against their will, can be beneficial for them in the long run. It sets them up to keep getting child support even after their welfare is repaid to the government, and without having to navigate the labyrinthine family court system on their own, including paying a lawyer and court fees.

Yet attitudes around cash assistance among many child support officials continue to evolve.

In 2017, another of New Mexico’s neighbors, Colorado, implemented a new law that allows all monthly child support payments made by fathers to be “passed through” directly to their kids, without being intercepted by the government.

The results have been clear. When dads know their money will make it to their children, they pay more, they pay more often, and they pay through the official child support system, rather than sending the moms cash whenever they happen to have some, research shows. They have also been shown to be more likely to keep their jobs instead of working in the underground economy and more likely to formally acknowledge paternity of their children.

In the first two years after the Colorado law was enacted, poor families in the state received $11.7 million more in child support, and monthly collections jumped by 76% in current TANF cases. Colorado counties, initially resistant to the policy change because they thought it would put a dent in their budgets, now support it because more dads are cooperating with them, said the state’s child support director, Larry Desbien.

Research also makes clear that allowing child support to flow to families makes low-income mothers more likely to work, because they can afford child care. And every dollar that goes to moms and kids saves the government many times more in the future, when they will be less likely to rely on social programs like food stamps and Medicaid.

Finally, several experts said, going after child support to recoup welfare is only marginally cost-effective for the government. That’s in part because fathers in TANF cases are so often poor themselves, and pursuing payment can require tracking them down, taking them to court or jailing them at taxpayers’ expense.

Yet the New Mexico Human Services Department and many others across the country continue pressuring poor single mothers to sign over their child support rights to the state to keep that trickle of revenue flowing.

When Albuquerque resident Alyssa Davis applied for public assistance for herself and her baby boy, Zeppelin, she didn’t expect to be hassled about child support requirements because she was in a committed relationship with the father. (They are now married.)

She said her interactions with the Human Services Department started out friendly but turned contentious when she mentioned that the dad was not, in fact, a deadbeat. “They didn’t take too kind to that,” Davis said. She said that a caseworker tried to get her to say that the father wasn’t as involved a parent as she was claiming, so that the state could go after him for child support as repayment for providing her with assistance.

“It’s like they wanted us to not be a family unit,” she said, “which I thought was the opposite of what this whole welfare thing was supposed to be about.”

Asylum seekers protesting for the right to live and work legally in Belgium took part in a hunger strike for more than 7 weeks at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste au Beguinage church, in Brussels, July 19. (photo: Reuters/Yves Herman)

Asylum seekers protesting for the right to live and work legally in Belgium took part in a hunger strike for more than 7 weeks at the Saint-Jean-Baptiste au Beguinage church, in Brussels, July 19. (photo: Reuters/Yves Herman)

Nearly 500 migrants and refugees held a two-month-long hunger strike in a bid to obtain the right to live and work legally in Belgium. But what was achieved and what comes next?

But one day in July, his atrophied muscles could no longer hold him upright. After more than a month on hunger strike, the 27-year-old Algerian, who has lived as an undocumented migrant in Belgium since 2014, collapsed on the floor.

Lying on a hospital bed a little while later, Lakoighet recalls the emergency doctor speaking to him while she administered fluids via IV.

“She said, ‘Why are you doing this hunger strike? Belgium is small. We can’t accept all of you.’”

Lakoighet is one of about 470 undocumented migrants in Brussels who participated in a nearly two-month-long hunger strike as part of a dramatic bid to obtain the right to live and work legally in Belgium, or at least to convince the government to clarify its conditions for obtaining legal residence.

The strike, which began on May 23 following months of protests, was put on pause on July 21 after a series of closed-door meetings between organisers and government representatives. It is a pause that no doubt saved lives; medical experts had begun to warn that deaths among the protesters were imminent. It may have even averted governmental collapse; two parties had threatened to pull out of Belgium’s fragile coalition government within hours of a first death among the protesters.

But it is also a pause that comes on the back of months of pushback from the government, sometimes accompanied by rhetoric that seemed intended to appease Belgium’s increasingly powerful anti-migrant far right.

Commitments from the government remain vague, and the protesters’ most concrete demand – a set of clear criteria on which people’s residency applications on humanitarian grounds will be evaluated – has so far been rejected altogether.

Now, as the weeks pass and the protesters regain their health, many of Belgium’s estimated 150,000 undocumented migrants are left asking what exactly has been achieved, and what comes next.

‘We went from providing advice to providing food’

One thing that is for certain is that the strike managed to draw attention to the plight of undocumented people in Belgium and elsewhere in Europe.

Since the coronavirus pandemic first swept this continent in early 2020, many European residents have been able to weather the crisis by relying on state social services. Government furlough schemes for businesses and workers, for example, have kept many afloat who might otherwise have lost their footing from lack of income, either because they got sick with the virus itself or as a result of closures due to lockdowns.

No such safety net has been available for those without legal residency documents in Belgium and many other European countries, however, despite the fact that the majority of undocumented people work in sectors hit particularly hard by the pandemic, such as restaurants, home and office cleaning and small-scale construction.

Even before the pandemic, Europe’s approximately 3.9 million undocumented migrants routinely worked long hours for little pay in the informal economy. Like elsewhere in Europe, most of Belgium’s undocumented migrants, many of whom have lived here for years or even decades, have long managed to survive under such exploitative conditions, albeit barely.

But the pandemic was a breaking point, explains Lilana Keith, a senior advocacy officer at the Platform for International Cooperation on Undocumented Migrants (PICUM), an organisation that advocates for undocumented peoples’ rights in Europe.

“Overnight, our [organisation’s] members had to change from providing advice to providing food,” she says.

Some European countries have responded more practically than others during the COVID crisis, according to Keith. Portugal, for example, granted temporary residency status to people with pending applications, thus avoiding swaths of people falling into irregularity due to bureaucratic slowdowns caused by the pandemic. Other states have extended employment protection benefits to undocumented people during the pandemic or taken other measures to help ensure people do not fall through the cracks due to their irregular residence status.

Belgium, meanwhile, is among the states that have, for the most part, resisted both one-off and structural policy changes to accommodate its undocumented population during the pandemic. With the notable exception of healthcare and vaccine access, the country’s undocumented have largely been left to fend for themselves during an unprecedented global crisis.

Undocumented in Belgium

So desperate was the situation for undocumented people in Belgium that, in January this year, around 200 people, including Lakoighet, set up camp on the stone floor of a 17th-century church in central Brussels in an effort to gain greater visibility. As more undocumented protesters joined in, the group spread out to two other locations across the city.

Throughout winter and spring, the group and its supporters staged protests calling for government attention to their plight. It was to no avail. Within just the first few weeks, Sammy Mahdi, secretary of state for asylum and migration, dismissed the church occupation as “blackmail”.

Mahdi and his team also consistently rejected the protesters’ demand for a set of clear criteria on which applicants for legalisation of residency would be evaluated. Such criteria, like long-term residence, integration, employment prospects and so on, are articulated by a number of other EU member states in their regularisation policies. But in Belgium, the working policy defers all humanitarian-based regularisation applications, which is the category into which most of the country’s undocumented people fall, to a case-by-case assessment procedure evaluated entirely according to government discretion.

Failure to satisfy the biggest piece of procedural criteria – that applications are made from one’s home country and not from Belgian territory – is often the only element of a rejected file on which an applicant receives feedback. And even then, it is not clear why some individuals or families are granted an exception to this requirement while others in similar situations are not.

The result, say experts, is a process that is profoundly lacking in transparency. For undocumented people, the lack of procedural transparency and written criteria for regularisation can mean it is impossible to make sense of one’s immigration prospects, which in turn renders an already uncertain existence even more precarious. And with virtually no insight into one’s chances for regularisation, most undocumented people are unwilling to risk leaving their life in Belgium to submit an application from their home country. With Europe’s ever-tighter borders, they may very well not get back in.

According to Alyna Smith, a senior advocacy officer for PICUM: “The government is really taking the extreme position by refusing to engage in something so basic.”

“It’s not an either-or between [government] discretion and something more systematic, clear and defined. There are countries that do this differently. Some of them have a structural process in place, and others have a [regularisation] programme periodically. So the mechanisms and the specifics of it can be discussed.”

But discussion has simply not been on the table here. And after months of demonstrations without progress, the protesters escalated to a hunger strike, and for a few days, even a thirst strike.

Even though Belgium has suffered some of the highest COVID-19 mortality rates in Europe, every undocumented person Al Jazeera spoke to for this article had more or less the same thing to say: Yes, the virus has been frightening, but it is nothing compared to the everyday fear of living without legal residence.

Locked down without money for food

For 20-year-old Nada Radouani and her mother, both of whom participated in the hunger strike, the lockdowns meant there wasn’t enough money for food.

Radouani is an upbeat Gen Z-er. A polyglot and makeup addict from Morocco, she blends in easily with the cafe-goers around her. But, she emphasises, she is not like the others, because she is undocumented.

“A lot of people when I tell them I’m undocumented, they’re like: ‘But you’re so pretty!’”, she says, laughing.

Radouani and her mother came to Belgium in 2017 after Radouani’s father died and the family lost its main support. With minuscule job prospects and the challenges of carrying on as a single mother, Radouani says her mom made the difficult decision to relocate the two of them to Europe.

Before the pandemic, Radouani’s mother worked as a cleaner in offices and private homes around Brussels. Radouani, meanwhile, worked to complete her high school diploma while earning an income as a French and Dutch interpreter for Arabic speakers who sought help navigating bureaucratic appointments. Like nearly all undocumented people, their work was “in the black”, or outside the formal economy.

When the pandemic hit, all but a few sporadic house-cleaning jobs screeched to a halt.

“It was so hard,” Radouani says. “There was just enough money to pay the rent and bills, but that’s it. No more.”

Mother and daughter avoided going hungry altogether thanks to solidarity organisations that distributed food during the lockdowns. Until, of course, the pair decided to join the hunger strike.

While the pandemic brought Radouani’s life to a point of desperation, she has long been aware of her vulnerability as an undocumented person. She was only 16 when she and her mother first flew to Brussels and moved into the apartment of an acquaintance. Soon, that acquaintance, an older man who is a legal Belgian resident, started demanding favours.

“He was like: ‘If you let me take your virginity, I can help you get your papers and you won’t have to pay rent,’ stuff like that,” she recalls.

Furious, Radouani threatened to go to the police. But then it dawned on her: “I got scared that if I go to the police, they’ll just say you’re not legal here anyway.”

Instead, Radouani and her mother found somewhere else to live.

The hunger strike, while worth it, was incredibly difficult, Radouani says. But it was especially hard on her mom and others.

“I was talking to the old women, they were saying: ‘I feel like this is my last day. I know I will die.’ Some of the women, they couldn’t even go to the toilet.”

Now that the strike is suspended and Radouani has completed high school, she wants to go to university to become a lawyer. But once again, not having papers is an obstacle.

So, spooked by rumours that the hunger strike has prompted extra immigration enforcement to patrol the streets, Radouani is sitting tight for the moment.

“I don’t want to move right now. “I’m just going to present my [residency application] to the lawyer, wait until the answer comes, and then when I get my papers I can go to the university.”

‘Being undocumented is more difficult than the virus’

One person who brought a note of sunshine to the long days and nights of the occupation and hunger strike is Chouaib Lakoighet, who, in addition to his kickboxing and kung fu prowess, also plays flamenco guitar.

In the church where he and other protesters have slept since January, his playing helps soften the sometimes hard edges of protracted protest. Music was especially helpful, say other protesters, when the hunger strike began and anxieties and tempers could run hot, as foregoing food for days on end will do to a person.

Like the soulful flamenco he plays on the guitar, Lakoighet has mellow, spiritual energy. He speaks freely of past heartbreaks and being “in the zone” during martial arts competitions.

Lakoighet came to Belgium from Algeria in 2014, when he was 19 years old, on a sports competition visa. In Belgium, he says, he saw the potential to pursue his martial arts dreams beyond what he could do back home. Life in Brussels was far more difficult than he expected, namely because legal residence was harder to obtain than he realised, but he managed to build a life for himself anyway. He started working as a barber, a trade he learned in Algeria.

Like some of the other hunger strikers, Lakoighet spent time in a detention centre for people without documents. Those eight months felt like 10 years, he says.

Especially traumatising was witnessing the suicide of a Congolese friend in the detention centre. The man, says Lakoighet, had been in Belgium for 20 years and was facing the prospect of being forcibly returned.

“They treated him like an animal, not a person,” recalls Lakoighet, who says he cannot shake the memory of seeing the man hanging in the bathroom shower.

Both closed migrant detention centres and forced returns are major issues for advocates for undocumented rights, who say there are more humane, not to mention more constructive, ways to enforce migration policies.

After his release from the detention centre, Lakoighet went back to working and martial arts training.

Before the pandemic, life wasn’t too bad. He was winning kickboxing competitions and working as a barber, a job he says he particularly loves even if he was paid below minimum wage.

But, of course, the coronavirus would put an end to this.

“Those people who have documents, it’s easy because the government helps them out,” says Lakoighet. “All the barbershops here were closed for like one year.”

Without an income or means to survive, Lakoighet joined up with other protesters to occupy the church and, ultimately, embark on a hunger strike in the name of earning the right to live in Belgium legally. He estimates he lost about 10kg (22 pounds) during the strike.

Asked if he was frightened to move into close quarters with 200 other people in the middle of a pandemic, Lakoighet laughs.

“Why would we fear? The situation when you don’t have documents is even more difficult than the virus.”

Now that the hunger strike is on pause, he is waiting, anxiously, for a decision on his freshly submitted residency application.

“I hope just that [Sammy Mahdi’s] office does what he promised,” says Lakoighet. “If he doesn’t, we’ll start again, of course. We won’t give up. Ever.”

‘Being tough on migrants is good for your polls’

What exactly those promises are, though, no one can say for sure. Nothing was committed to paper during the meetings between protest organisers and government representatives. Some of the hunger strikers seem to be under the impression that they will, as a group, be granted legal residency. Mahdi’s office, however, not only adamantly denies this but also reiterates that the secretary will not make any changes to current policy.

One thing the protests may have accomplished, but only for the 470 or so who participated in the hunger strike itself, is assurance that the substance of their residence applications will be considered despite the fact that they were filed from within Belgian territory and not the strikers’ home countries. Normally, one must first successfully make the case that travelling to one’s home country to file such an application cannot be done for one reason or another.

Or, at least, some professionals and volunteers working with the hunger strikers are operating under the impression that this has been accomplished. But like everything about the oral agreement between the hunger strikers and the government, rumours abound and clarity is nearly impossible to come by.

When asked for clarification on this point, a spokesperson for Mahdi’s office denied that the hunger strikers were “exempt from the condition to prove that the file cannot be introduced in the home country while others are held to give that proof”.

“To the organisations assisting the hunger strikers [it] is confirmed that, in case of denial, a motivation will be given on the reasons why a humanitarian stay cannot be given,” the spokesperson said.

But these are not the finer details on which the government wants public attention.

Instead, the act of government generosity intended for public fanfare, a short-lived pop-up immigration information office situated near the church occupied by Lakoighet and others, promptly flopped. Touted as a product of successful negotiations with protesters to end the hunger strike, the “neutral zone”, as the information office was called, was almost immediately overwhelmed by hundreds, and by some estimates thousands, of undocumented people from across Belgium seeking everything from status updates on their files to frantic pleas to get in on what was rumoured to be a one-off collective regularisation.

Just two days after the hunger strike was put on pause, Mahdi’s team closed the neutral zone’s doors to everyone but the hunger strikers themselves. Days later, the government closed the office altogether and installed officials outside to distribute multilingual flyers declaring that rumours of collective regularisation were “fake news”.

For many undocumented people who did not participate in the hunger strike, something seems fishy. Surely, the government must have promised some kind of preferential treatment to the hunger strikers in order to bring a pause to the strike. But what? The word “traitor” has been thrown around more than once.

According to Brenda Odimba: “The only thing that was achieved [by the hunger strike] was division.”

Odimba is an activist who is helping some of the hunger strikers prepare their immigration files, including Lakoighet. She interprets the moves by Mahdi’s office as being both manipulative of the country’s undocumented population, where some now resent one another over perceived privileges earned through the strike, and an effort to protect itself in the face of xenophobic Flemish politics.

She cites an interview with Mahdi published two days after the hunger strike was put on hold in which the politician claims it is too easy to live illegally in Belgium.

“I was so shocked when I read this. We fought for the rights of these people, and he’s basically saying we’re now going to make sure that life becomes even harder for them.”

Odimba’s conclusion? “Being tough on migrants is always good for your polls.”

Other politicians in Belgium were even tougher. Theo Francken, a far-right Flemish politician who served as secretary of state for asylum and migration under Belgium’s last full national government, argued that all hunger strike participants should be blacklisted from regularisation.

Mahdi, who is also a politician from Belgium’s Flanders region but is part of a different party than Francken, maintains his decisions are not influenced by his more far-right Flemish colleagues. But it is hard to interpret his hardline stance as entirely independent of the extraordinarily anti-migrant sentiment dominating Flemish politics these days.

In a survey published in May, the extreme-right nationalist party Vlaams Belang took the top spot as the most popular party in Flanders. Anti-migrant policies are among the strongest issues put forward by the party, whose members often lean on Islamophobic fear-mongering to rally constituents. As a crisis unfolded in Afghanistan following the United States’ withdrawal, for example, one prominent Vlaams Belang politician was accused of promoting genocide when he tweeted, “Someone once told me that Afghanistan can only become a prosperous, free society if 70 percent of Muslim males are exterminated (because they are essentially no better than the Taliban)”.

The hunger strikers are now compiling fresh residency applications. One by one, they are submitting their paperwork. But their fate remains unclear.

Juliette Arnould, a former lawyer hired to work with the hunger strikers for the next several months, worries about how the group will cope with disappointing news.

“I think for those who get a negative decision, it will be very, very hard for them,” she says. “Most of them tell me they can’t sleep because of the stress. There was a guy who tried to kill himself here during the hunger strike.”

A lifetime of struggle

No one is asking Belgium to simply open its doors and let everyone in, clarifies Mamadou, who asks that we not use his real name because he does not want friends and family back home in Gambia to know he is undocumented.

A veteran activist and organiser for undocumented people in Belgium, Mamadou did not participate in the hunger strike but supports the strikers’ general objectives. Although the strike yielded nothing in terms of practical progress, he says it was helpful in bringing domestic and international attention to the struggle of undocumented people in this country.

Arriving in Belgium in 2008 in pursuit of political asylum, Mamadou says he was shocked when his claim was denied.

“I thought I was just waiting for a positive result, being a Gambian at that time. With a dictator, that stupid guy, in power.”

Since then, he has applied to regularise his residency a number of times but has yet to succeed.

Before the pandemic, Mamadou worked for a man who connected him with odd jobs around Brussels. He unloaded cargo, cleaned houses, and pinch-hit for construction companies. He used up nearly all of his savings when work stopped during the lockdowns. Now, gradually, work is coming back.

He says he makes sure he is paid at least eight euros ($9.48) an hour, which is more than many other undocumented people but is still less than the legal minimum in Belgium.

“I have no choice,” says Mamadou. “This is the situation of undocumented migrants. You accept any job you are given.”

His second job, though, is working on behalf of other undocumented people. As a founding member of the Coordination des Sans-Papiers de Belgique, an umbrella organisation connecting groups of undocumented migrants across the country, he has become something of an expert on the rights of the undocumented and bureaucracy in Belgium.

‘A failure in the system’

During the pandemic, the government has turned to Mamadou and his colleagues to help communicate critical health information to other undocumented people, like the importance of wearing a mask and how to get medical care, including the COVID vaccine.

One bright spot for undocumented people in Belgium is that the vaccine has been made available to everyone, and healthcare, in general, is accessible to people regardless of legal status. The vaccine, in particular, is not yet as easily available to undocumented people in many other European countries.

The discrepancy is frustrating for PICUM’s Alyna Smith.

“It’s really jarring to see, on the one hand, Belgium really standing out for all its terrific work around access to the vaccine, and on the other hand leaving people utterly behind by essentially refusing to engage on something so basic as trying to work to find solutions around what is clearly a failure in the system.”

Again, a lot comes down to the criterial ambiguity and the profound uncertainty this causes among an already marginalised population.

“There are people who are regularised in Belgium, it’s not that nobody’s using it,” explains PICUM’s Lilana Keith. “But the numbers are so much lower than they could be because people just don’t trust it, they don’t know if they will be eligible and they don’t know what the ramifications would be, what they’re risking [if their application is denied]”.

Mahdi’s office disagrees.

“Every year, thousands are given an exceptional staying permit after a decent investigation, and a possibility of appeal,” said a spokesperson for Mahdi’s office in an email. “There is no need to change this only because some people did receive a negative decision or because some people do not submit any application.”