Live on the homepage now!

Reader Supported News

He said he uses a finger pad with bristles and a beef-flavored toothpaste and the dogs tolerate it well and the brushing spares them dental miseries so it made sense. Oliver carefully describes the grasshopper chewing and washing its face and flying away and then —

I don’t know exactly what a prayer is.

I do know how to pay attention …

how to kneel down in the grass,

how to be idle and blessed, how to stroll through the fields,

which is what I have been doing all day.

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

with your one wild and precious life?

Paying attention is what Oliver does in her poetry, it’s what her poems are about, walking out in the natural world and seeing what’s there. Unlike most poets working today, she doesn’t write about her own troubles. She writes:

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on …

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination.

I came across an Oliveresque passage in a journal of mine from when I was 12, standing one September evening after dishes were done, behind our house, under my dad’s apple trees, and my mother at the piano playing “Abide with me” and I wrote:

Abide with me, another autumn day.

Night falls, the sky fills with the Milky Way.

An old piano, golden apples and

Dishes are done, my dog’s nose in my hand.

It’s a sweet little souvenir of a September evening in 1954, north of Minneapolis, and a boy wanting to preserve the wonder of concurrence, the hymn, the stars, the apples, the dog’s cold wet nose. He declined to draw any conclusion or to bring himself into the poem. Below the poem he notes that the word “racecar” is the same forward or backward.

Years later, I’m sitting in a steakhouse, hearing about brushing dogs’ teeth and thinking about Mary Oliver’s grasshopper while ten feet away eight drunks in their twenties sit around a table, having a wonderful time being stupid and very loud.

I don’t think I’ve been loud often in my life, but I’ve certainly been stupid. Once I got myself a cabin in the woods of Wisconsin with a separate workroom, 10×15, on stilts, with a stove and a big window looking into the trees, no house or road in sight. I sat at a table looking out the window and it was startling, when a deer walked out of the underbrush or a bird flew by. Shocking once, when a porcupine stopped and looked up at me.

I am not Mary Oliver, however, and don’t have the patience to think about a porcupine and design a poem around him (or her, I also don’t recognize gender except for deer), and I am not a birdwatcher. I was working on a book, The Book of Guys, and none of the guys was a hunter or hermit or forest ranger. And after a year I concluded that peace and quiet made me uneasy. A porcupine is interesting for a few minutes and maybe if I were looking up at the stars and smelling apples as someone played the piano and a porcupine put his nose in my hand, I could get a poem out of it, but poetry isn’t my line. Sorry, I’m a money writer.

And then I met my friend who became my lover and she was a New Yorker and I abandoned the cabin and workroom and we married in 1995. She is a daily walker but prefers Central Park with its great variety of humanity. Out of mistakes comes happiness. We gain good judgment by exercising bad. Had I made the enormous mistake of buying myself a dog, I might’ve been comfortable in isolation and I’d still be there today, a cranky bachelor, unvaccinated, not brushing its teeth or my own, listening to Fox, with twenty “Keep Out” signs posted, a pile of hundreds of empty Jack Daniels bottles, and a couple of loaded AK-47s by the door. I much prefer talking to you than listening for intruders. Thank you for that.

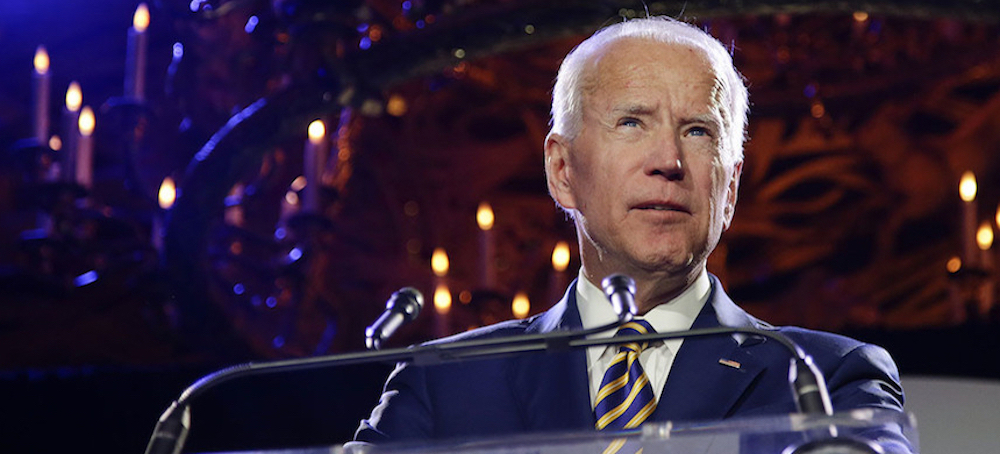

Joe Biden. (photo: Frank Franklin II/AP)

Joe Biden. (photo: Frank Franklin II/AP)

Trump has said he will cite “executive privilege” to block information requests from the House select committee investigating the events of that day, banking on a legal theory that has successfully allowed presidents and their aides to avoid or delay congressional scrutiny for decades, including during the Trump administration.

Biden, however, probably plans to share that information with Congress if asked, White House press secretary Jen Psaki told reporters Friday.

“The president has already concluded that it would not be appropriate to assert executive privilege,” Psaki said. “And so we will respond promptly to these questions as they arise and certainly as they come up from Congress.”

She added the White House has already been working closely with congressional committees and others “as they work to get to the bottom of what happened on January 6th, an incredibly dark day in our democracy.”

Psaki also noted that no one from Trump’s team has reached out to the Biden administration to formally request that Biden use executive privilege to block information requests from the Jan. 6 select committee.

“We don’t get regular outreach from the former president or his team, I think it’s safe to assume,” she said. “I would say that we take this matter seriously.”

Biden’s decision could have significant political and legal ramifications. Members of the investigative committee argue that Trump no longer enjoys the protection of executive privilege, encouraging the White House to push aside institutional concerns about sharing information with Congress and aid the panel in an investigation focused on what Democrats and a handful of Republicans have called an assault on democracy.

Trump has derided the committee’s work as partisan and is promising to fight its effort to collect information and testimony related to the attack.

“The highly partisan, Communist-style ‘select committee’ has put forth an outrageously broad records request that lacks both legal precedent and legislative merit,” Trump spokesman Taylor Budowich said in a statement Thursday. “Executive privilege will be defended, not just on behalf of President Trump and his administration, but also on behalf of the Office of the President of the United States and the future of our nation.”

On Friday, Psaki said Biden would lean toward disclosing information but stopped short of saying it was a blanket policy.

“It’s an eye to not asserting executive privilege. And obviously, some of this is predicting what we don’t know yet, but that is certainly his overarching view,” she said.

Asked whether there was something that they would not turn over to Congress, Psaki said she did not want to “get ahead of a hypothetical.”

“What’s important for people to know and understand is that’s the principle through which we’re approaching this,” she said.

In response to the House panel’s request, the National Archives has already identified hundreds of pages of documents from the Trump White House relevant to its inquiry. As required by statute, the material is being turned over to the Biden White House and to Trump’s attorneys for review.

The committee’s Aug. 25 letter to the National Archives was sweeping and detailed, asking for “all documents and communications within the White House on January 6, 2021, relating in any way” to the events of that day. They include examining whether the White House or Trump allies worked to delay or halt the counting of electoral votes and whether there was discussion of impeding the peaceful transfer of power.

The letter asked for call logs, schedules and meetings for a large group, including Trump’s adult children, Trump son-in-law and senior adviser Jared Kushner and first lady Melania Trump, as well as a host of aides and advisers, such as his attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani.

The committee has focused, in part, on seeking information about whether the Trump White House and members of Congress played any role in encouraging the demonstrations, which interrupted the constitutionally mandated confirmation of electoral votes and unleashed a series of violent confrontations with the U.S. Capitol Police.

More than 650 people have been charged with crimes in connection with the insurrection. Many were charged with obstructing a federal procedure and for knowingly entering or remaining in a restricted building. Documents and testimony could show whether White House officials and members of Congress encouraged or supported those actions, congressional staffers said.

An eviction. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

An eviction. (photo: John Moore/Getty Images)

As the Delta variant continues to surge across the United States, so too has the housing and eviction crisis, with more than 11 million households now behind on rent. Most of those evicted are Black or Latinx, and the majority are single women with children. We speak with a single mother and a high school student who have faced eviction and went to Washington, D.C., this week to help Congressmember Cori Bush and Senator Elizabeth Warren introduce the Keeping Renters Safe Act to reinstate the federal pandemic eviction moratorium. “We need the eviction moratorium and the National Tenant Bill of Rights,” says Vivian Smith, a tenant activist with the Miami Workers Center. We also speak with Faith Plank, a 17-year-old housing activist in Morehead, Kentucky, who was evicted in March and says she has felt “the pain of that eviction” every day since. “I can’t focus on school when I’m worried about how I’m going to go to bed tonight,” says Plank.

Despite data linking evictions to a rise in COVID-19 cases and deaths, the Supreme Court struck down the Biden administration’s temporary extension of eviction bans last month. This week, Congressmember Cori Bush and Senator Elizabeth Warren introduced the Keeping Renters Safe Act to reinstate the federal pandemic eviction moratorium and give Health and Human Services permanent authority to enact an eviction ban during public health crises. The bill was unveiled at an anti-eviction rally Tuesday outside Congress led by a delegation of 11 tenants from across the United States who have been evicted or are facing eviction and mounting rental debt. This is Vivian Smith with the Miami Workers Center.

VIVIAN SMITH: I’ve been forced to choose between food, rent too many times. Many of us had to make the choice or the choices between our health or our homes. The rent eat first.AUDIENCE MEMBER: That ain’t right!

AMY GOODMAN: Vivian Smith and the tenant justice delegation met with congressmembers and the Biden administration in D.C. this week. Vivian Smith joins us now from Miami, a single mom who’s faced eviction with her children, a leader with the Miami Workers Center. And another member of the tenant delegation joins us from Morehead, Kentucky. Faith Plank is 17 years old, a high school student who faced eviction in March along with her mom and younger sister.

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Let’s begin with Vivian. We just watched you at that rally. Can you talk about what’s happened to you and the significance of Congress passing a bill to reinstate the eviction moratorium?

VIVIAN SMITH: Good morning.

What happened to me was I got evicted, trying to pay my rent and see about my kids’ eating, health. And I was invited on a trip with me and other tenants all across the world. We came with one purpose and to make it be clear and known that we need the eviction moratorium and the National Tenant Bill of Rights action put in place, so that tenants like me and my tenants that was from all over the walks of different states came together, so that Congress, Bush can join us as enforcing that we need this eviction moratorium, for real tenants like me and my colleagues that joined me on the D.C. trip, to be in effect. You know, we are the people that living it, and we are the people that going through it.

AMY GOODMAN: Vivian, at the start of the pandemic, you said you had to quit your job at an Amazon warehouse to avoid getting COVID. How has the pandemic worsened the eviction crisis, especially where you are, in Florida and in Miami, which you call a city of renters? Talk about your decision to leave Amazon.

VIVIAN SMITH: My decision was to better for my health. At the time, the warehouse was getting very infested with the virus. And I chose to just stay home, because I didn’t want to endanger my kids’ health with that. So, from staying home, I fell behind in my rent. And I knew that, OK, I have to go back, even if it means risk my health, risk my kids’ health. So, I did go back to work to come up with the money.

And once I came up with the money to go to the rent office, to the landlord, now to present the money, and found that I was put in eviction. And that really took me to a whole ’nother space and a whole ’nother living another nightmare of not wanting to go back to my car.

AMY GOODMAN: So, then what happened?

VIVIAN SMITH: And when I went in to pay the rent, they said, “Well, Ms. Smith, we can’t take it.” It was over, like, $2,000. And they say they can’t take $2,000. And I immediately just went to a space: “Well, OK, you know, can you give me my money order back? And I’ll try to move with it. I’ll try to find somewhere else to move.” And then, following the next day, she was like, “Ms. Smith, you were so upset, but we wanted to talk to you.” And then, that’s the part where I had to pay them to stop the eviction, and also pay over $2,000-and-some for rent.

And that’s when I became in contact as a tenant with the Miami Workers Center. And from there, I have been a member and fighting not only for me but all the other ones that came to D.C., all my fellow members that came to D.C., to join the movement of the eviction moratorium and the National Tenant Bill of Rights, to be clear, to make it clear that’s what we’re fighting for. That’s what we need, and that’s what we want.

AMY GOODMAN: Faith Plank, you’re also part of this historic delegation that went to Washington, working with congressmembers and the Biden administration to reinstate the moratorium. You’re 17 years old. We are glad we could get you on before you go to high school today. You’re from Kentucky. Can you talk about what happened to you and your family?

FAITH PLANK: Yeah. Thank you so much for having me on. I’m actually at high school right now. I was able to find a room to make this call.

In March, my entire neighborhood was evicted to make room for a shopping center. I feel the pain of that eviction 'til this day. Just yesterday morning, I was driving my sister to school, and we sat and cried in my car for 10 minutes, because she looked over at me and she said three words. She said, “I miss it.” We both instantly started sobbing and holding each other's shaking bodies, because even after six months of being evicted, it’s still with us. We still feel the pain of that.

And I guess that’s why it’s so important to me that this eviction moratorium is passed through Congress, because me, along with all of those tenants, have faced an eviction or a pile of rental debt during this pandemic. And with that eviction moratorium being passed, it could have saved my home, and it could have saved 75 other families’ home in my community.

AMY GOODMAN: So, you lived in a mobile park, the North Fork Mobile Home Park in Morehead, for six years, paying $125 a month for rent. It’s not that you stopped paying rent; it’s that they were — they destroyed the mobile home park for this center. So, what happened next to you, your sister and your mom?

FAITH PLANK: So, we were used to pay $125 in lot rent, because we owned our trailer. We were only given 45 days to leave the park, along with 75 other units of affordable housing. And with that comes the source of panic, because in a town that has no affordable housing, and a single mom, it’s extremely difficult. We were able to find an apartment. Then we now pay $950 a month for our rent. That is over $800 more than what we were used to paying. And it’s almost impossible to make that work.

AMY GOODMAN: So, your mom works full time and has to take care of you guys?

FAITH PLANK: Yes, my mom works full time, and now she’s working anywhere from 60 hours a week, as well as I work. Normally I was working up to 30 hours a week to try to help support my family because of this. Because of school, I can no longer work 30 hours a week, which should never be an issue that a 17-year-old has to face, choosing between work and school because of an eviction that wasn’t her fault.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how does this affect you emotionally, Faith, as a teenager, where you’re going to stay the next night, when you’re in school, when you’re with your friends?

FAITH PLANK: I mean, I am still affected emotionally. Just, I mean, every morning as I drive to school, I drive my little sister along with me, and to get from the new apartment to school, we have to drive past what was my home. And when you look up on that hill, it’s almost unimaginable that that used to be my home, because all you see is dirt and bulldozers. It’s now a construction site. So I have to hold back tears every single day because I have to be strong for my little sister. But once I get to school, I can’t hold that in anymore. So I spend a good hour of my first day at school crying, because I can’t focus on school when I’m worried about how I’m going to go to bed tonight.

AMY GOODMAN: So, here you are in Kentucky. You’re talking to us from your high school in Morehead. But last week you were advising White House advisers. What was that like, to be part of this delegation to change the law of the United States around evictions?

FAITH PLANK: [inaudible] gone through similar [inaudible]. I chaired a meeting with Gene Sperling, who is the American Rescue Plan coordinator for the White House. And at that meeting, I told Mr. Sperling that we know the path to getting a full eviction moratorium passed through Congress is very narrow. And the last time, they didn’t have the votes to do it.

But we also know that when the White House wants something done, they get it done. And we know that when Gene Sperling wants something done, he gets it done. So, my ask to him was to have the American people’s back. We need the White House’s leadership, and we need his leadership, to get this eviction moratorium passed through Congress. And we need — we need to make sure that the White House does everything they can to make sure that’s done.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, final words to Vivian Smith in Miami. Cori Bush, the congressmember, and the senator, Elizabeth Warren, have introduced this bill for a federal eviction moratorium. What do you say to the American people?

VIVIAN SMITH: That we went on a mission to make it clear and make it known that the eviction moratorium and the national bill, tenants’ rights, need to be put in effective, like now, like today.

And to know that we have Senator Cori Bush behind us, you know, someone that has gone through what I’ve gone through as a tenant, as a single mother, also what my team that came to D.C. have gone through and are going through, and for people like Faith, that is a 17-year-old that’s trying to get her education — you know, and I take my hat off to her, because I really care so much for her, meeting her, that her mom and me have a lot in common, because I looked at my daughter every time I dropped her off, and I wanted to know how a 12th grader dealt with sleeping in a car, and knowing that when she get out of school, she got to work with her mom on a second job ’til about 10:00 at night and still try to get up and go to school.

So, I would say to, you know, Congress and them that we need that — they need to have our back. We need to know that they have our backs in this eviction moratorium and the national bill, tenants’ rights. We need it.

AMY GOODMAN: We want to thank you, Vivian Smith, for being with us, speaking to us from Miami, with the Miami Workers Center, and Faith Plank, with Kentucky Tenants, both tenant justice advocates who faced eviction, went to Washington, D.C., in a historic delegation. Faith, thanks so much for joining us from your high school.

In addition to concerns about COVID safety, workers at Amazon have expressed frustration about impossibly high productivity expectations and are therefore starting to unionize. (photo: Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

In addition to concerns about COVID safety, workers at Amazon have expressed frustration about impossibly high productivity expectations and are therefore starting to unionize. (photo: Stephanie Keith/Getty Images)

The warehouse workers’ fight enters its second round, just when everyone thought it was finished.

The old railroad still runs through Bessemer, but most everything else has been sucked out by modern commerce. The town is emblematic of many that have seen their small business districts destroyed, first by Walmart and its imitators, more recently by Amazon. Which makes it somehow appropriate that Bessemer is the site of the most immediate threat to Amazon’s non-union business model — a fight entering its second round, just when everyone thought it was finished.

In March, the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU) lost its historic bid to unionize the Amazon warehouse on Bessemer’s outskirts by a more than 2‑to‑1 margin. But in early August, federal labor officials found Amazon’s anti-union tactics — including a mailbox for ballots on company property — violated the law; they recommended a new election. The National Labor Relations Board will issue its final decision in the coming weeks or months, but it’s widely expected to uphold the recommendation. Preparations are already underway, quietly, on both sides.

Stuart Appelbaum, RWDSU president, says Amazon has already resumed anti-union messaging to employees at the warehouse. But the union also didn’t stop organizing after the first vote — in fact, Appelbaum says, the organizing committee of workers is even bigger now. “We never went away,” Appelbaum says. “The organizing has accelerated.”

While Appelbaum won’t make any firm predictions about the outcome, he believes a second vote could be better for the union. He says Amazon’s advantage came from those who voted early in the seven-week election period and that, as time went on and workers had more opportunity to engage with the union, more of them came around.

Sustaining any long-term organizing strategy inside an Amazon warehouse is difficult because the rapid turnover rate requires the union to constantly educate new employees on what the organizing drive is all about. But, according to Appelbaum, pushing forward with an election in Bessemer is just one part of the larger project of organizing Amazon, the corporate behemoth that’s driving fundamental changes to the nature of work worldwide.

“It’s not about our union; it’s about the entire labor movement,” Appelbaum says. “Amazon is not something where you just try an election, see what happens, and then you walk away. No. The battle to reform Amazon is going to be an ongoing priority.”

The Amazon warehouse in Bessemer sits behind a shield of trees amid freshly cleared suburban sprawl, roughly the size of a shopping mall with a parking lot to match. Past a set of floor-to-ceiling turnstiles in the lobby, the wide-open space bustles with activity, resembling an IKEA store but without the customers. Just before the late afternoon shift change, one employee, a man in his 30s, sat on a cement block outside the exit, waiting for his shift. He voted for the union in the first election and said he will again. Things needed to change, he said: Managers are inexperienced and employees are overworked to exhaustion and he feels like the facility is unsafe. “They only see numbers,” he said, “and not the people struggling.”

Amazon did not respond to a request for comment.

Another man, younger, wandered out to vape during his break. He voted against the union and felt the pitch was misleading and unclear. Being young, he thought any seniority structure the union imposed would leave him at “the bottom of the totem pole.” And, he said, “Most of the people here never worked for a union. You gotta tell ‘em what you can give ‘em.”

These two men roughly embody the breakdown in the warehouse — those whose disgust with the job outweighs any union trepidation, and their opposites. After chatting for about 10 minutes, the workers told me someone inside had called the police to get me. (The Bessemer Police Department appears to routinely patrol the parking lot; I witnessed two sweeps in one hour.)

Before I left, I asked for their names. Both declined. The pro-union worker smiled and shook his head. “Everybody’s just trying to keep their healthcare, dog.”

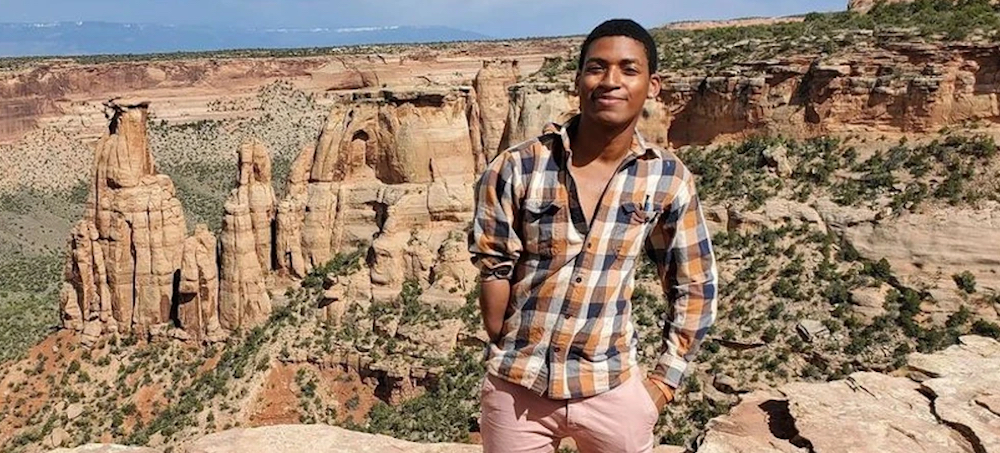

Daniel Robinson has been missing since June 23. (photo: GoFundMe)

Daniel Robinson has been missing since June 23. (photo: GoFundMe)

Some families are turning to retired cops and lawyers to find out what happened to their children because they feel police aren’t doing enough.

Robinson, a 24-year-old geologist who is Black, was last seen on June 23 leaving a work site near Buckeye, Arizona. About a month later, on July 19, a cattle rancher found his Jeep in a ravine a few miles from the job site. That’s when Daniel’s father, David Robinson, hired McGrath, who specializes in reconstructing car accident scenes.

After surveying the evidence, McGrath came to the conclusion that the Jeep had crashed in a different spot than where it was found.

“Immediately we know we have a suspicious missing persons case, so we're trying to convey that to the police,” McGrath said. “They wouldn’t listen to me.”

Now that’s changed, in light of the death of YouTuber Gabby Petito, 22, whose remains were found at Wyoming’s Grand Teton National Park on Sunday. The FBI have ruled her death a homicide, and a massive manhunt is underway to find Petito’s boyfriend, Brian Laundrie, a person of interest in the case.

The story has garnered international media attention, but it’s also thrust cases like Robinson’s into the spotlight, with many noting that missing persons cases involving Black and Indigenous people don’t receive such intense coverage—if any at all. Some families, including Robinson’s, turn to private investigators and lawyers to help them find answers when they feel the police response is lagging.

Last week, Buckeye police released an update about Robinson’s disappearance, saying that police used ATVs, cadaver dogs, a drone, and a helicopter to search 70 square miles for him; they also asked for tips. McGrath said police are now consulting with an accident expert, but they’ve lost three months of valuable time.

Police are “trying to do what’s right at this point, but I feel that it’s a little too late,” Robinson’s brother Roger Cawley-Robinson said in an interview with CNN. “My sister that lives in Arizona and my father did a lot in the beginning, trying to push and get things moving, pleading with the police, you know, begging for them, ‘Hey, can you help us get a search? Can we do an air search? Can we get something?’ And I just think the lack of action initially is what's leading us here.”

In a statement to VICE News, Buckeye police Chief Larry Hall said, “Investigators are working tirelessly to find answers and bring closure to Daniel’s loved ones.” The police force did not respond to specific questions about the case, but they provided VICE News with a 54-page portion of the police report about Robinson’s disappearance, which listed more than a dozen people authorities have contacted and the area they searched for him.

According to media interviews, Robinson, who is 5-foot-8, has black hair and brown eyes, and was born without a right forearm, was in frequent communication with his family. His dad described him as being “very outspoken” and driven, learning how to play the French horn and trombone despite missing a hand, and graduating from college with honors.

The police report said one co-worker indicated Robinson had been acting “strange” when he left the job site and turned down a road leading further into the desert instead of toward the main road.

There were a few things that struck McGrath as odd when he started working on the case: the damage to the Robinson’s Jeep didn’t align with its surroundings; it was going 30 miles an hour with no braking before the airbags were deployed; and after the airbags went off, the ignition was turned on 46 times and the Jeep was driven an additional 11 miles.

McGrath said he and Robinson’s father had a meeting with Buckeye police early on to present that information.

“They dug their heels in and basically didn't want to do anything with me,” McGrath said, noting that police also turned over all the evidence to him because they didn’t feel it was suspicious—a move he said is bizarre.

“They could find something that turns it into a homicide. And now they've released all the evidence so they don't have a case.”

McGrath’s company charges $200 an hour, and he’s had six different employees work on Robinson’s case. But he said they are not charging Robinson’s father, who is a veteran with a disability. He said the cost at this point would be tens of thousands of dollars. Robinson’s father is crowdfunding for expenses related to the search.

The Robinsons are not the only ones who’ve looked beyond law enforcement for assistance finding out what happened to a missing or dead loved one. Other families have hired private investigators and lawyers—even ordered second autopsies because they felt the police investigation was insufficient—a time-consuming and potentially costly venture that advocates say should not be necessary because policing is a public service.

In a separate case, Illinois State University student Jelani Day, 25, went missing on Aug. 24; he was last seen at a weed dispensary in Bloomington, Illinois. On Tuesday, his brother, D’Andre, told VICE News he felt the police had slowed down their momentum in the search for Day.

Their mother, Carmen Bolden Day, told Newsy the family hired a private investigator to investigate what happened to her son.

“I know about Gabby, the missing girl, and she's been missing for two days and her face is plastered everywhere and the FBI is involved,” she said.

“I want them to look for my child like they're looking for her. He is not a nobody. He is somebody... And it makes me mad because this young white girl is getting that attention and my young Black son is not.”

On Thursday, a coroner identified a body that had been floating in the Illinois River earlier in the month as Day’s, according to NBC News.

"There are no words to clearly communicate our devastation," Day's family said in a statement. “Throughout these 30 days, our very first concern was finding Jelani, and now we need to find out #WhatHappenedToJelaniDay.”

Even after a missing child is found, learning what happened to them can be a frustrating and painstaking process.

Last October, 15-year-old Quawan Charles went missing in Baldwin, Louisiana; he was found dead in a sugar cane field three days after his family reported him missing.

The story went viral after Charles’ family released a graphic postmortem photo showing injuries to his face.

Baldwin police did not notify state police about Charles’ disappearance as required by a state statute, nor issue an Amber Alert, according to civil rights attorney Chase Trichell, who represented Charles’ family. Local police also didn’t ping Charles’ cellphone.

It wasn’t until Charles’ family went to a neighboring police department, who pinged the teen’s phone, that Charles’ body was discovered. Despite a number of suspicious circumstances surrounding Charles’ death, police also took months to arrest the woman last seen with him.

Trichell told VICE News he came across 10 other cases involving white children who went missing in the same area dating back to 2016. In every case, he said, police issued a Level II advisory, which results in state police putting out a media alert that a child is missing.

“The only difference in Quawan Charles' case was that he was a Black male,” Trichell said. “Had they issued a Level II advisory, people would have known, the police would have known, his cellphone would have been pinged; he would've been found sooner.”

Charles’ family is now suing Baldwin police, which Trichell said will help them gain access to evidence police won’t willingly provide.

He and fellow civil rights attorney Ronald Haley have taken on Charles’ and a number of other cases pro bono. But he said families should not be forced to create their own shadow investigative teams in order to find out what happened to their kids.

“You would expect the bare minimum out of facilities and departments that are funded by taxpayer dollars… investigating crimes, finding missing children, not killing its own citizens,” he said. “And we continuously keep seeing cases where the police are doing more harm than good, particularly in the Deep South and particularly in Black communities.”

Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp. (photo: CNN)

Guantanamo Bay Detention Camp. (photo: CNN)

The Department of Homeland Security insists that there are no plans to transfer Haitian migrants from the U.S.-Mexico border to Guantanamo Bay, where the U.S. has long housed asylum-seekers encountered at sea.

Still, the contract solicitation published last week has alarmed some immigrant advocates, who are already critical of the Biden administration's decision to quickly expel more than 1,000 Haitian migrants back to a country that is still reeling from recent disasters.

According to the contract solicitation, which was first reported by NBC News, the facility at Guantanamo Bay "will have an estimated daily population of 20 people." But the service provider should be prepared to "erect temporary housing facilities for populations that exceed 120 and up to 400 migrants in a surge event. This equipment includes tents and cots, and the contractor must be able to have these assembled and ready with little notice."

The solicitation specifies that "at least 10% of the augmented personnel must be fluent in Spanish and Haitian Creole. Air transportation to/from the facility is the sole responsibility of the service provider."

Since the Sept. 11 attacks, Guantanamo Bay has been known primarily as the site of a U.S. military prison where some detainees have been held for years without trial.

But the naval base is also home to a DHS immigration detention facility. In the early 1990s, the base was used as a refugee camp for Haitians fleeing by boat after the democratically elected president of Haiti, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, was deposed in a military coup.

At its peak, the refugee camp held more 12,000 Haitians under what immigrant rights advocates described as deplorable conditions.

"Sending people who are seeking protection to a place that is notorious for being treated as a rights-free zone is the last thing that the Biden administration should do," said Eleanor Acer, director of refugee protection at the nonprofit Human Rights First. "It is nothing more than a blatant attempt to evade oversight, due process, human rights protections and the refugee laws of the United States."

But DHS insists the solicitation has nothing to do with the situation in Del Rio, Texas, where migrants have crossed into the U.S.

"[DHS] is not and will not send Haitian nationals being encountered at the southwest border to the Migrant Operations Center (MOC) in Guantanamo Bay," wrote Marsha Espinosa, the assistant secretary for public affairs at DHS, on Twitter.

The solicitation is simply "a typical, routine first step" in a contract renewal, she wrote.

A jaguar. (photo: San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance)

A jaguar. (photo: San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance)

However, until very recently, experts had measured only the vegetation in areas destroyed; never had the biodiversity loss caused by fires been assessed. A new scientific study published in Nature – “How deregulation, drought and increasing fire impact Amazonian biodiversity” – translates this impact into numbers: to a greater or lesser extent, 93 to 95% of 14,000 species of plants and animals have already suffered some kind of consequence of the Amazon’s fires.

The study, which involved researchers from universities and institutions in the U.S., Brazil and the Netherlands, analyzed data on the distribution of fires in the Amazon between 2001 and 2019, when the region saw record rates of major fires, despite high rainfall.

“At the time, the fires attracted a lot of international media attention, and we were interested in better understanding their consequences, where they had happened, and which areas were occupied by fauna and flora,” says biologist Mathias Pires, a professor and researcher at the Department of Animal Biology at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp).

Using satellite images, the researchers compared the areas affected by fires – from 103,079 to 189,755 square kilometers of the Amazon rainforest – with habitats of 11,514 plant species and 3,079 animals (including vertebrates, birds and mammals).

“We were surprised to find that the habitats of most plant and animal species had already been affected by fires and that this impact continued to increase over time, despite the best conservation efforts,” says Brian Enquist, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona and a lead author of the article.

Primates suffered the worst impacts

The analysis indicated that, for some species, more than 60% of their habitat had been burned at some point in the last two decades. For the majority of the Amazonian plants and animals, though, the impacted areas represent least than 10% of their habitat range. While this sounds like a small percentage, a little bit of habitat loss in the Amazon can already be consequential for species survival. “Any lost habitat is already too much,” says Danilo Neves, professor of ecology at the Institute of Biological Sciences of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG).

He explains that some groups of rare and threatened species have restricted distribution in the Amazon, such as the white-cheeked spider monkey (Ateles marginatus), which is endemic to Brazil and classified as endangered on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), meaning that its probability of extinction is high.

“That species depends a lot on the standing forest,” says Pires. “Monkeys need trees for displacement, food and shelter. They hardly ever move or feed on the ground.”

The white-cheeked spider monkey had 5% of its range affected by fire. “Five percent of the range impacted in 20 years is a lot,” he says. “What will happen in another 20 years, or 50…? We need to consider that, from a biological point of view, that’s very fast loss of habitat.”

Pires stresses that primates are under the highest threat from Amazonian fires. To draw a parallel with another animal species, he uses a bird – the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin). Classified as threatened on the IUCN list, it ends up being relatively less affected by forest fires since its habitat range can cover virtually the entire Amazon.

As for plants, which, unlike animals, cannot escape the flames, the situation is even more disturbing. The tree species Allantoma kuhlmannii had about 35% of its range impacted by fire.

Unlike the Cerrado, where plants are more resistant to fire and drought, Amazon vegetation is adapted to closed environments and moist soil; when the flames end, the plants can hardly recover, and that part of their habitat may be lost forever.

Since the study focused on measuring the number of species impacted by fire, it did not look for any visible change in animals’ behavior or habitat.

“Given the scale, scope and growing impact of fires across the Amazon, it’s likely that animal populations have already been affected by habitat loss and the opening of more remote areas to hunting,” Enquist believes.

Less enforcement, more fires

By overlaying data on fires with the habitat ranges of flora and fauna, the researchers noticed three fire cycles in the Amazon, which are directly associated with distinct political contexts in Brazil.

In 2001 to 2008, lack of strict environmental enforcement in the country served as fuel for more frequent fires in larger areas. In the following period, 2009 to 2018, enforcement policies managed to curb deforestation. However, in 2016, even though Brazil’s environment protection laws were praised globally, enforcement loosened, and deforestation started to rise again in the Amazon.

In 2019, when current president Jair Bolsonaro took office, the situation worsened. High forest destruction rates continued, driven by federal government rhetoric in favor of mining, against demarcation of indigenous lands, and critical of the work of non-governmental organizations.

“Our results clearly show that forest protection policies had a dramatic effect on the rate of impact of fires and on Amazonian biodiversity,” stresses Enquist.

The international survey points out that, in recent years, there have been fires in more central parts of the Amazon, including areas close to rivers, which is a new trend. “Fire consolidates deforestation. Deforested areas can regenerate, but that would require much more time and investment after the fires,” says Neves.

Risk of biodiversity loss and more extinctions

Scientists worldwide have made clear what needs to be done to restore the Amazon, that being to reduce deforestation, prevent fires and, consequently, protect the habitats of millions of plant and animal species. The formula to do so exists and has been used in the past: stronger commitment to environmentalism, effective law enforcement, forest monitoring, and support for environmental agencies.

Brazilian researchers Danilo Neves and Mathias Pires have no doubt that this is the only way to reverse the current scenario of habitat devastation and loss. “We know what to do. We have already solved the problem before,” says Pires.

The evidence is indisputable. Forest protection policies have a dramatic effect on fires and their impact on Amazonian biodiversity. But, if nothing is done, what can we expect from the future of life in this biome?

“We risk reducing and potentially losing large fractions of biodiversity, which is nature’s capital that gives resilience to climate change, and important ecosystem services that the Amazon provides to humanity,” says Enquist. “If nothing changes, we will see continued habitat degradation for most Amazonian species. As fire and deforestation now move into the heart of the Amazon and regions that are home to species inhabiting smaller geographic areas, the risk of extinction increases dramatically for thousands of forms of life.”

This article was originally published on Mongabay

Follow us on facebook and twitter!

PO Box 2043 / Citrus Heights, CA 95611

No comments:

Post a Comment